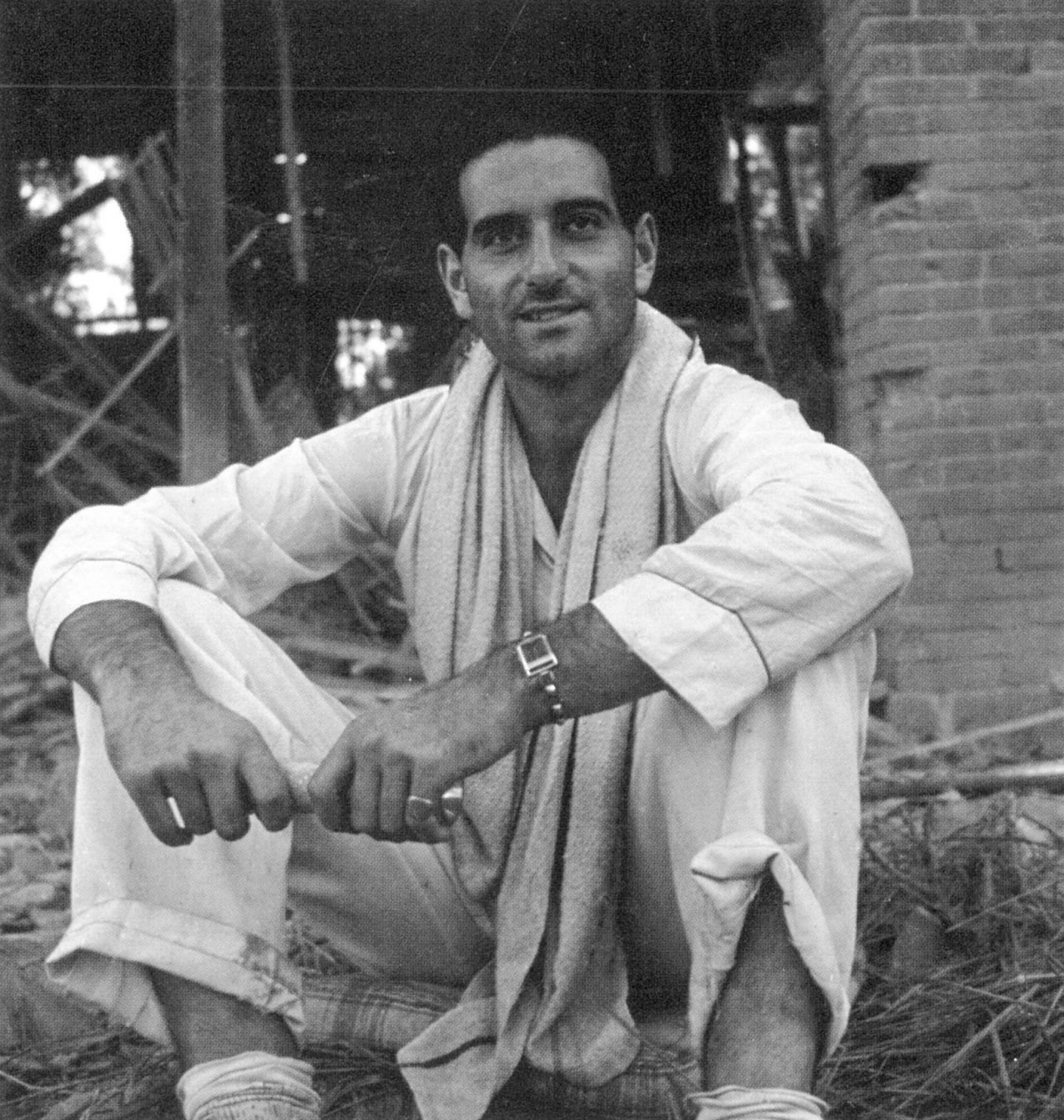

- Featuring photos taken by war correspondent Melville Jacoby, a new book published by Hong Kong’s Blacksmith Books depicts life in China’s inland capital city

This is an extract from A Danger Shared: A Journalist’s Glimpses of a Continent at War

Chungking – as English speakers referred to Chongqing in the early 20th century – was an unlikely capital. Deep inside China, in Szechuan (Sichuan) province, the city became the seat of Chiang Kai-shek’s government on November 20, 1937, when Chiang officially transferred China’s government from its previous long-time capital, Nanking (Nanjing).

In a mobilisation unlike any before, China’s leadership moved its entire government and industrial base more than 1,600km (1,000 miles) up the Yangtze (Changjiang) into Szechuan’s mountainous surroundings.

The move was a massive undertaking that involved relocating the entire Chinese economy and wartime manufacturing by carefully dismantling factories, loading them piece by piece onto trains and barges, and transporting them up the Yangtze to be rebuilt in and around Chungking, all amid the constant threat of airborne attacks.

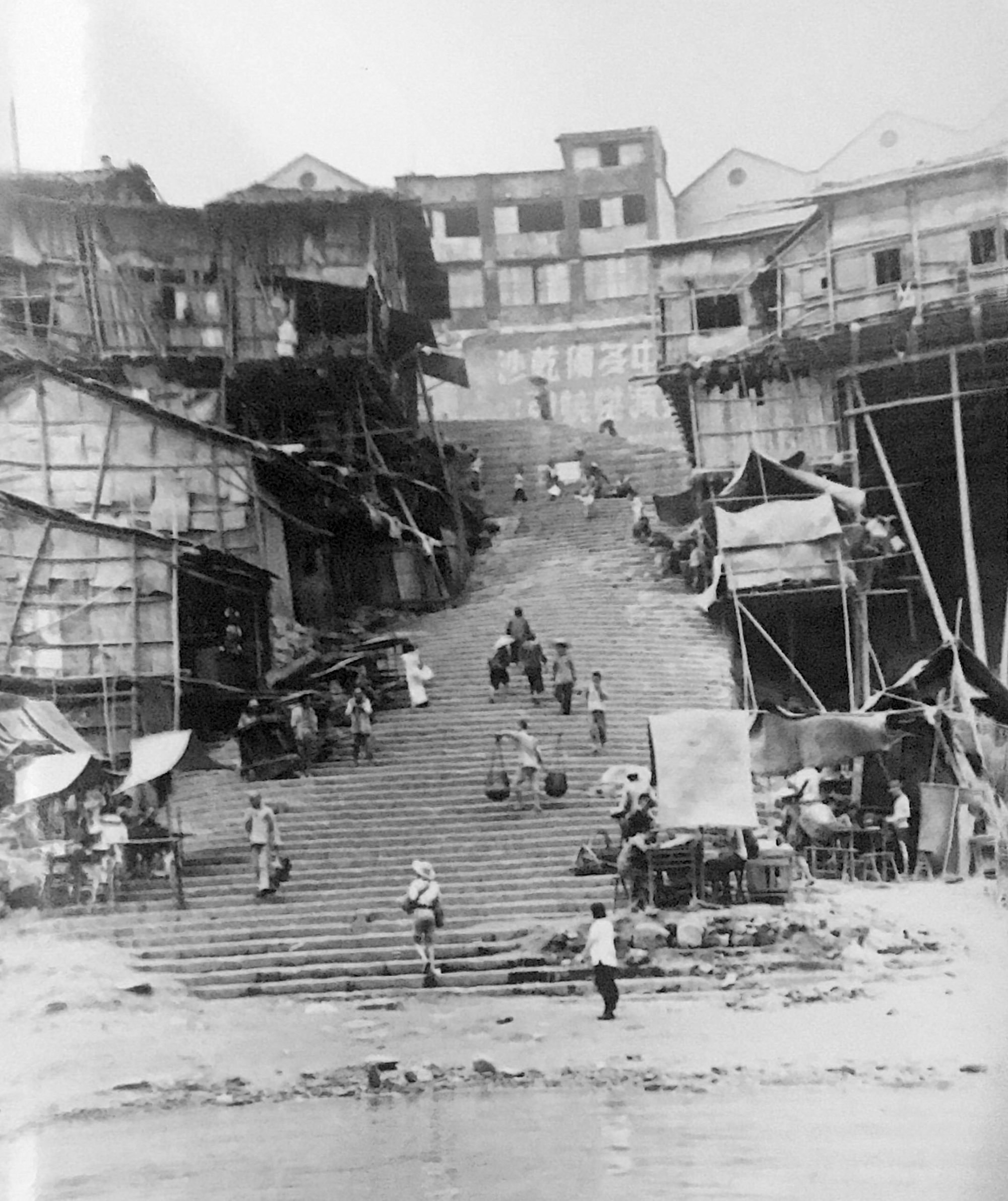

A city unlike any other in China, let alone the world, Chungking was built at the confluence of the Chialing (Jialing) and Yangtze rivers, climbing waterfront cliffs and sprawling over hillsides.

By 1940, most government facilities, many foreign embassies, and the city’s central business district packed the spear-like Yuzhong peninsula between the rivers, while some officials’ residences, embassies and foreign business interests dotted hills on the Yangtze’s southern bank.

Today, numerous bridges span both rivers and connect the megalopolis’ many districts, but in wartime Chungking, ferries and sampans were the only way to quickly reach the city centre.

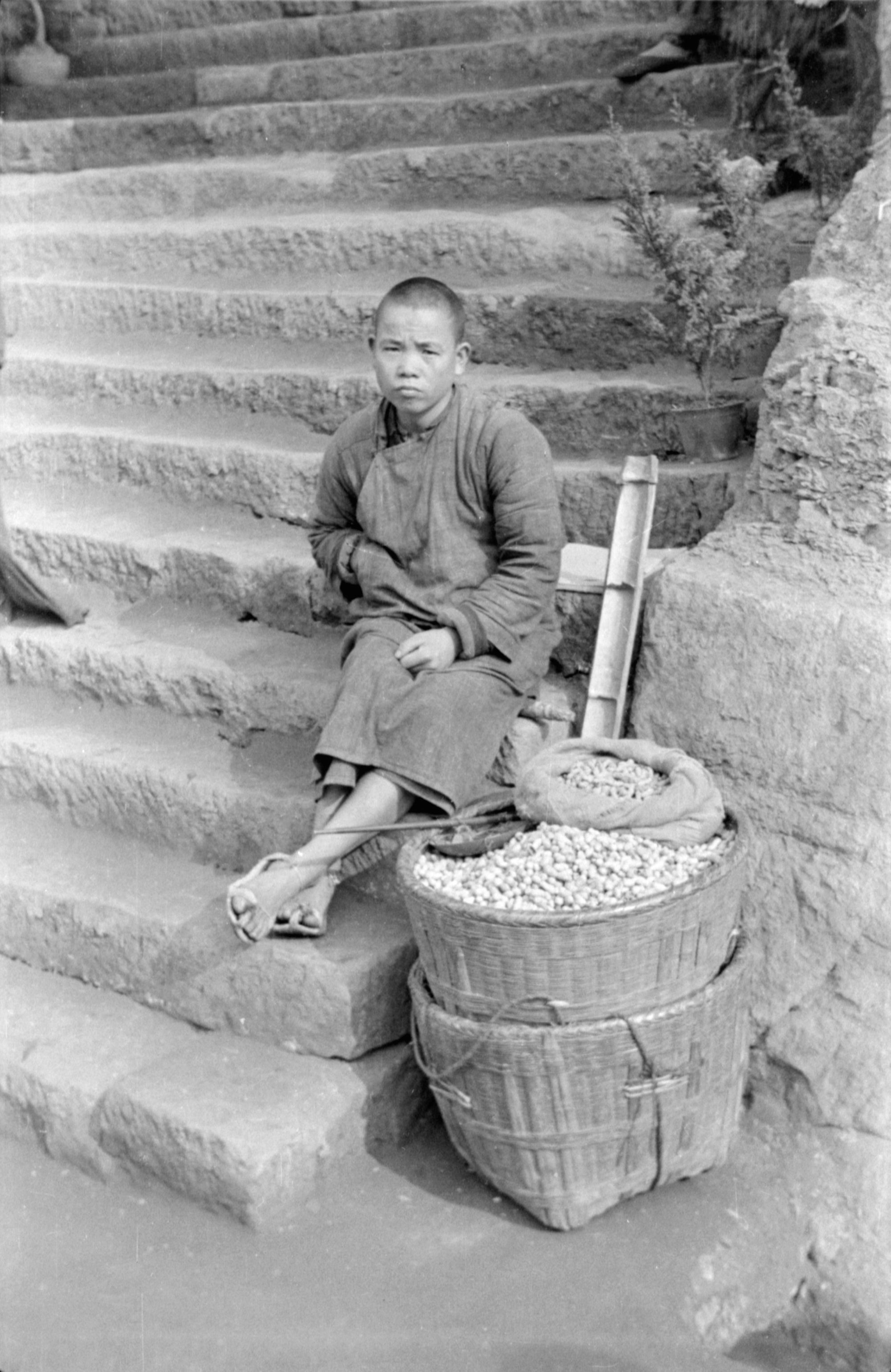

Once across the river, a long ascent loomed, either by climbing up hundreds of steep, often mossy and wet steps, or hiring porters who carried passengers up in bamboo chairs (a dehumanising and exhausting endeavour for porters and a rickety, bumpy ride for customers).

In some cases, mules and other pack animals were available, but Chungking’s hillsides were so steep and numerous that few practical alternatives to walking existed.

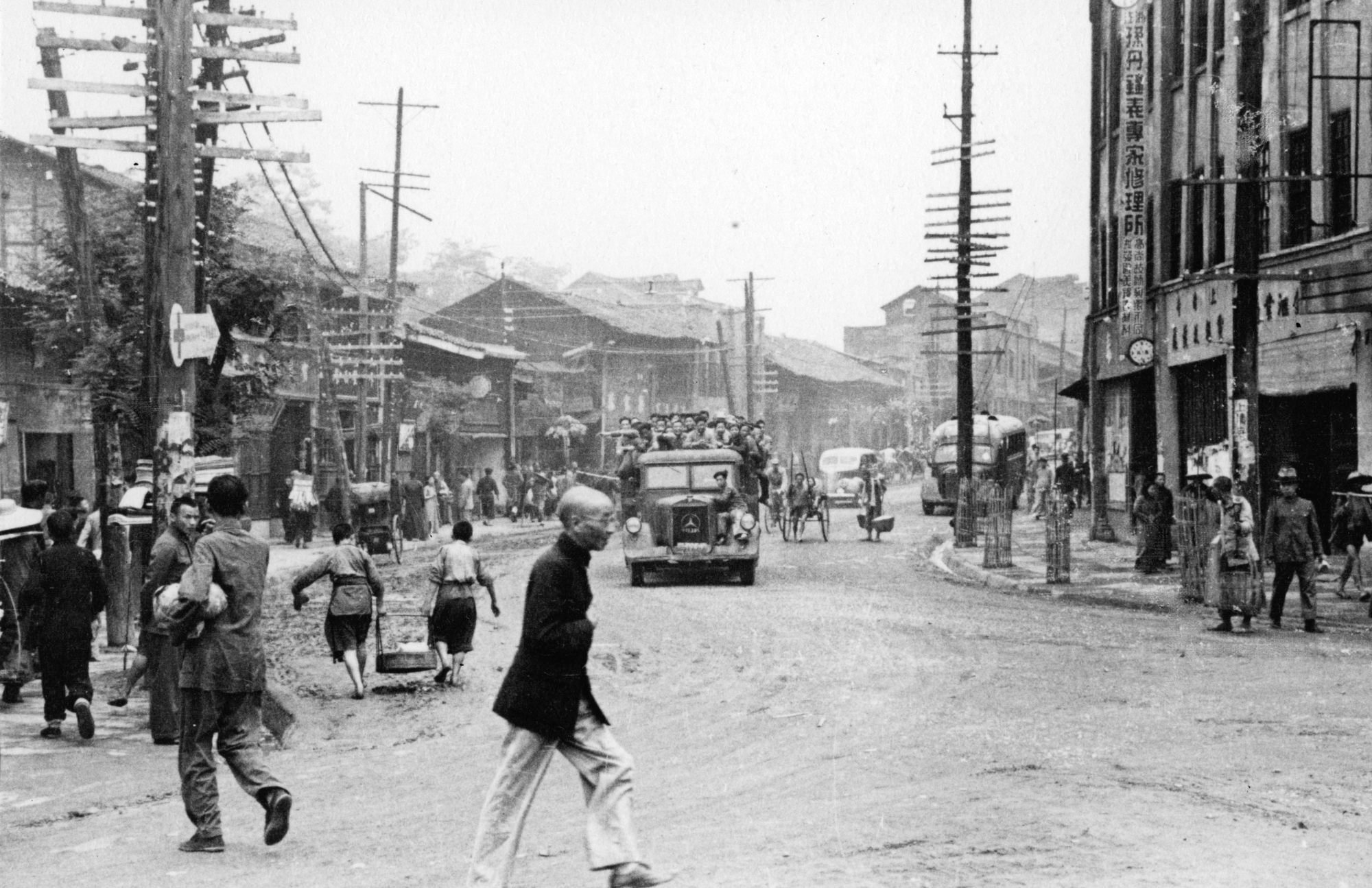

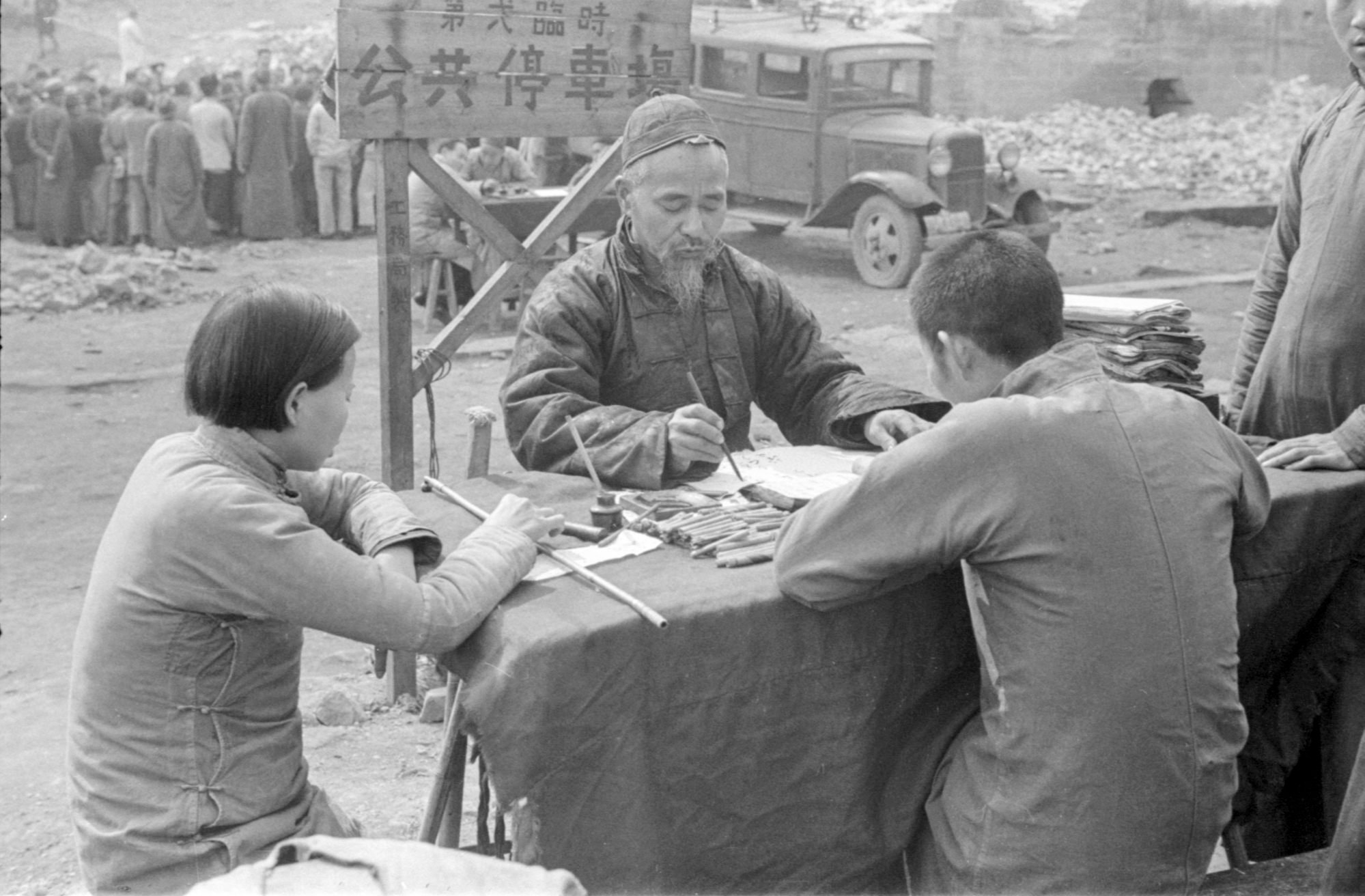

Paved roads with modern traffic controls did exist, but fuel was expensive and scarce. Only the wealthiest and best-connected Chungkingers had access to private automobiles.

Some heavily packed public buses served the central business district, but sturdy shoes and an occasional rickshaw were most people’s preferred transportation.

Now a massive megacity, Chungking was far smaller, though still bustling, when it was made China’s capital.

Chungking’s unique geography meant an adrenaline-laced arrival for Mel and other visitors. The city’s airfield was little more than a shallow, flat island in the centre of the Yangtze known as Shanhuba.

To reach it, incoming pilots traversed the ring of jagged mountains around the city, found the rough location of the island amid thick blankets of fog shrouding the river – clear days were bad days for transport flights, as they usually brought enemy planes loaded with another round of bombs – and sharply descended between the mountains, through the peaks and onto the gravel field.

Then, after a tedious series of customs procedures (sometimes hastened for VIPs or those with connections), came a sampan crossing to the steep cliffs.

Chungking was crowded, dirty, noisy and exhausting, beset by pestilence, inflation, hunger and a seemingly endless barrage of bombs, yet, it was also, in a way, exhilarating and vibrant, a place, Mel would write, where, despite its discomforts, “You get to like it.”

A Danger Shared: A Journalist’s Glimpses of a Continent at War is published by Blacksmith Books.