Profile | How the absurdist theatre of a Canadian trading company office sparked a Chinese humorist’s writing career

- Qi Yimin’s job with a trading firm in Montreal gave him the idea for his first book. ‘People from all over worked there. The environment was surreal,’ he says

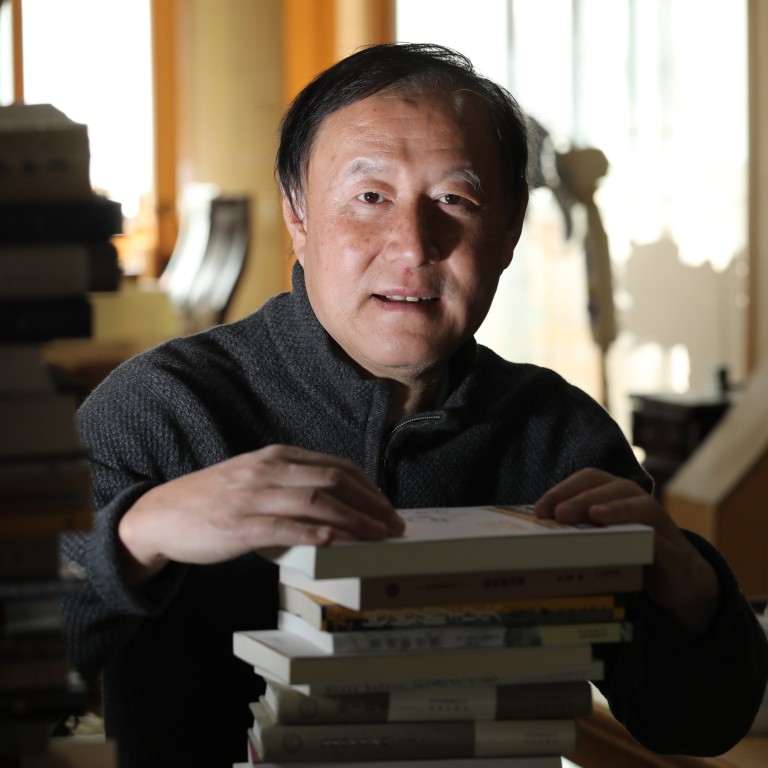

- The Beijing-based writer talks about earning a PhD from Peking University, reading a book a day, penning more than 40 of his own and the urge to leave a legacy

My father was from Liaoning province (in northeast China) and my mother was from Shandong (in the east). They went to Beijing in 1955. They were both early members of the Communist Party who had participated in the revolution.

After (the founding of the People’s Republic of China in) 1949, they worked in the People’s Government in the northeast for a number of years. That’s where my elder brother, Qi Yixin, was born. In 1955, they were sent to work in the capital and I was born there, in Xicheng district, on the west side of the old city, in 1962, the first true Beijinger in my family.

Country child

My childhood was relatively normal. Even though the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution started in 1966 it didn’t affect me much as I was still in kindergarten. All I can remember are a few revolutionary songs and dances we had to perform.

Politics only came to play a role in my life when (in 1969, eight years after the Sino-Soviet split) there was an undeclared border conflict between China and the Soviet Union that lasted for several months.

As my parents worked for the state, we were moved from Beijing to a village in Wenan county, in Hebei province, which was an arduous five- or six-hour journey from our home, although it would be much quicker today. I lived in the May Seventh Cadre School and ended up spending three years of my childhood in the countryside.

‘Hong Kong is my home’: composer Tan Dun on representing city through music

Page turner

We went back to Beijing in 1972. There weren’t many books around in those days, just a few old Russian novels. When I enrolled in middle school, however, there were some Chinese classics to read.

The book that impressed me the most was the (Qing dynasty epic) Dream of the Red Chamber. I read the whole thing when I was just 13 years old. Do you think young people these days would find the time to do that? For almost a year, I inhabited the pages of that book. To this day, I still love it. And I still read voraciously, finishing a book a day if I’m not too busy.

Spirit of change

My brother was part of the first generation to go to university after (paramount leader) Deng Xiaoping reinstated the university entrance exam in 1977. I followed in 1980 and majored in Japanese and economics at the University of International Business and Economics in (Beijing’s) Chaoyang district.

I was very fortunate. In those days, only about five per cent of the population could get a coveted spot at a good institution. Many people I meet today didn’t get a proper education – a pity, as it was an exciting time.

There was a spirit of change, “to learn from the world, to change China”, and for me that meant books.

We could get books from different universities so I’d go across town to Peking University at least once a month in search of good reading material.

Land of the Rising Sun

After I graduated, I went to work for China National Technical Import and Export Corporation, which was under the auspices of the Ministry of Commerce. My principal role was to facilitate technology transfers into the country.

I worked there for five years, three of which were spent in Japan working with companies like Mitsubishi Corporation and some other trading firms. I was given half a year of on-the-job training and then sent to Tokyo. I really liked it.

Japanese economic development had reached its zenith in the mid-1980s and, well, I was young. There were plenty of books to read as well as art galleries and museums to visit. I travelled all over the country visiting factories and got to know Japan well, although it took me a while to get used to sashimi, as we Chinese don’t eat raw fish.

These amazing Japanese toilets will leave you flushed with excitement

Life in the slow lane

In 1988, I returned to China as I had a girlfriend, Qiu Zhengqing, who worked at the Peking Union Medical College. Like many people back then, she wanted to go to Canada to study, so we married and left China together in 1989.

I did an MPA (masters of public administration) at Carleton University, Ottawa, simply because that was the subject I could get a scholarship to do.

The immediate and lasting impression of living in North America was the diversity of the people. In China and Japan, I’d only really encountered East Asians but in North America I’d meet all kinds of people and hear different languages beyond the national languages English and French.

It was also strange going from my role as a representative of a huge state-owned enterprise to becoming a student again, like being a car that was turned into a bicycle.

Write what you know

After graduating, we lived in Montreal. I worked in the import department of a well-to-do family business. People from all over the world worked there. The work environment was totally different from anything I’d experienced and quite surreal in many ways.

After that, I worked as sales manager for a hardware company but wanted to write about the experience in the previous company. So I penned the story Anecdotes from Liberty House by hand, usually while at my desk. When people took coffee and cigarette breaks, I wrote. When I had nothing to do, I wrote, sometimes, right under the nose of my boss. On a good day I could write 6,000 Chinese characters.

The book was eventually published in China in 2012. From that point on, I started writing more and more. If I’d not had such unique experiences working in these companies I don’t think I’d have much to write about.

Imperial China seen from a female perspective in show in Hong Kong

Return to China

My daughter, Qi Tianyi, was born in Canada. She was four years old when we came back to China in 1998.

I returned principally to take care of my parents as they were almost 70 and my brother was living in the United States. But it was nice to live in my hometown again.

My first book was published that year, Mother’s Tongue: My Experience Language Learning. I didn’t get a serious case of reverse culture shock but I did notice some of the changes taking place.

In 2000, Beijing was still a lot less developed than, say, Canada or Japan. There were still “loaf of bread” minivans on the roads and the only cars you ever saw were brands like the (Volkswagen) Santana.

The major difference between the Beijing we’d left in the 1980s and the city we returned to was the spirit of entrepreneurialism imbuing the place. There were opportunities everywhere.

In the 1980s, you were rich if you drove a taxi. By 2000, everyone wanted to be a big boss.

I’d say China’s culture of capitalism had already exceeded that of the West at that time and this era of enterprise would continue for a decade more.

From trader to teacher

I got caught up in the zeitgeist and started my own company importing Italian radiators. But the company went bankrupt in 2004, an experience I wrote about in my novel The Most Pitiful CEO in the World. After that, I started teaching at Beijing Language and Culture University.

As I was already over 40, I was hired as a “special teacher”, a position I still hold. I’ve taught so many subjects it’s dizzying, including business English, doing business with China for overseas students, Chinese language, politics, economics, literature and writing. I also undertook a PhD in comparative literature at Peking University during this period, while writing books at the same time.

I bought a computer in 2006 so I haven’t had to write books by hand and then get them typed up as I did in the early days. At any rate, I have been averaging a book or two a year since 1994. My secret is to publish the first draft without much editing. To date I’ve written over 40 books.

Words for the world

When I returned to Beijing, I saw that most of the tall buildings in the capital employed an elevator operator. This seemed funny to me as it’s unnecessary work, a lift can work by itself.

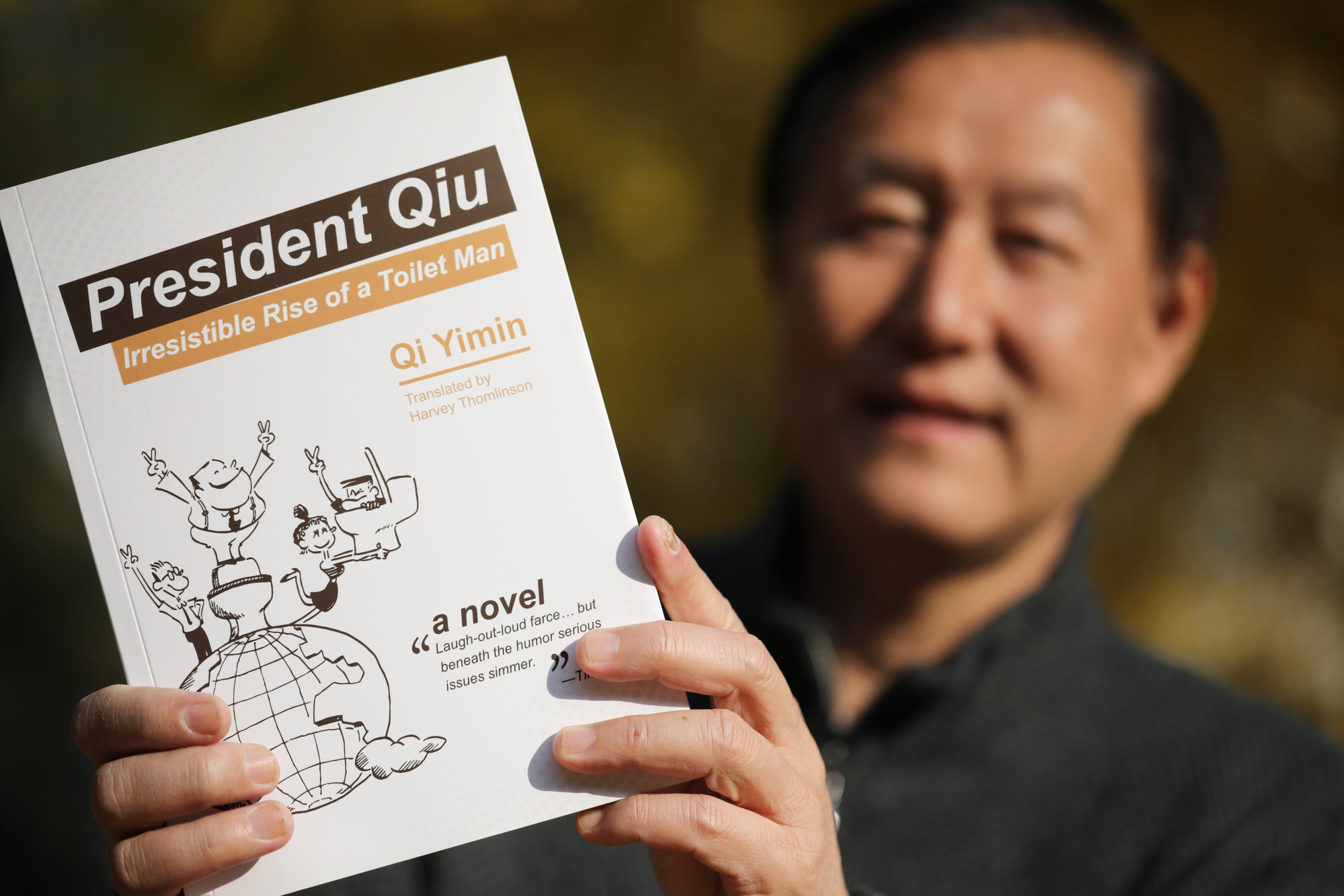

He has since translated another book of mine, President Qiu, Irresistible Rise of a Toilet Man, which has just been published. Both these books concern an intensely commercial period in modern Chinese history, one that is more or less over now. But I continue to write about the world I live in. For instance, I’ve already published a novel set during the pandemic.

You know, for me, life is writing, writing is life. We only live 70 years or so, so we need to leave something of ourselves behind. Whether you write about art or commerce, that’s not important. What is important is to document the age you live in.