Review | Vignettes from a side of China we don’t often see in Chinese-Canadian author’s short story collection Taobao

- The China of shiny Shanghai towers is nowhere to be seen in Taobao, Dan K. Woo’s sharply observed short story collection

- He delves into life in China’s small towns and the pull of cities on its rural youth, and shows a particular sympathy for his female characters’ plight

Taobao: Stories by Dan K. Woo, pub. Buckrider Books

The common themes are, in fact, loneliness, quiet desperation, resignation in the face of unpromising circumstances, social awkwardness and incomprehension. The stories often go nowhere, like the lives of their characters.

Boy meets girl. Things go wrong.

This is not the China of shiny Shanghai towers but of stagnant water and sour skies, of underground warrens home to migrant workers and of windblown plastic rubbish caught on fencing.

But if Woo isn’t trying to charm, he doesn’t try to shock, either. His sharply observed scenes are presented in spare and undemonstrative prose, and modern China is caught without judgment, as if seen with the detachment of a camera phone.

Woo is another writer of Chinese descent but Western sensibilities vividly portraying collisions between two cultures with a sympathy for both. But there’s neither Joy Luck Club-style melodrama here, nor any Shanghai Baby-like attempt to startle or titillate the bourgeoisie, be it Chinese or foreign in origin.

This collection was begun years ago while Toronto-based Woo was studying Chinese at Beijing’s Normal University. As a result several stories are set around campuses either there or at various private language schools, among often ill-educated foreign teachers selected primarily for their alien looks and willingness to put up with local conditions rather than for their English skills.

Other stories enter more directly into Chinese small-town life, into the willingness of families to sell their daughters into marriage to pay for the education of their sons and in turn to fund the acquisition of wives for them. Owing to China’s growing shortage of women it’s a highly competitive environment, and unsurprising that for a girl in one story “double happiness” means acting as wife to two brothers at the same time.

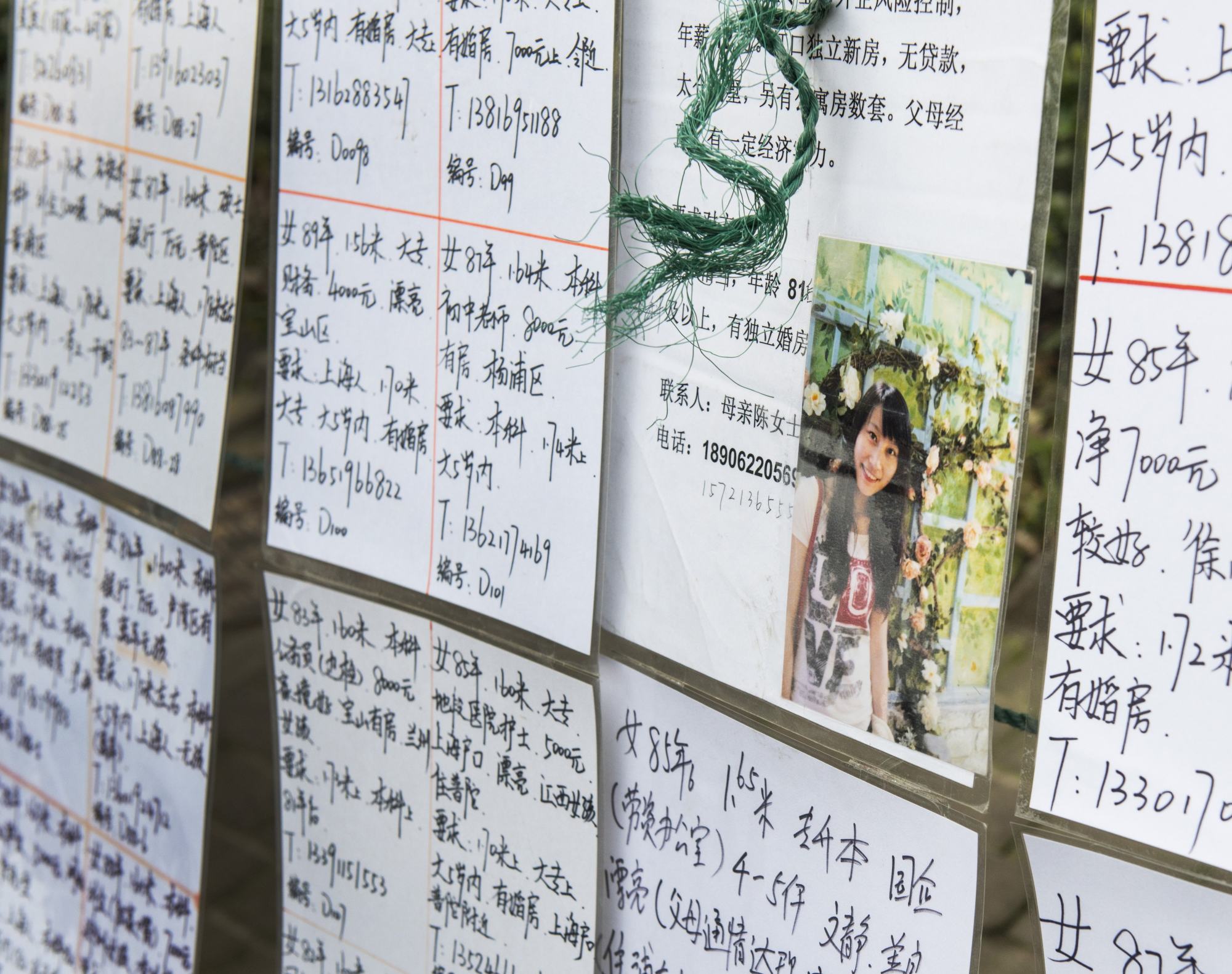

Woo seems to have a particular sympathy for his Chinese female characters, who are more poignantly described, being left in most cases with lesser expectations and fewer choices than men, constantly made conscious of their market value, and who are described as the often unwilling recipients of clumsy courtships via gifts (obtained from Taobao).

One young woman returns home reluctantly from an unsuccessful period in Shanghai to submit herself to her mother’s matchmaking and to be taken to marriage markets to look at potential partners. Her indifference seems to stem from the low quality of the male suitors until a closing hint that her tastes, not as yet understood by herself, may make the fulfilment of parental expectations unlikely.

The local women of the author’s own haphazard relationships are treated with greater warmth, while males are often blanks. But Woo takes to various characters incidental to the student or teaching milieu, such as an old man selling second-hand bicycles from a shack near his Beijing campus.

When Woo’s fellow language students buy new and shiny machines, instead, to their derision, he cannily buys a boneshaker that he has the old man repair. After a short time, only Woo’s bike remains un-stolen.

Teacher-student relationships are particularly problematic. In two stories Chinese students are unable to comprehend that their assessments of their own appeal may not be matched by those of foreigners who use an entirely different scale, or that their own sense of devotion is not a sufficient condition to merit an equivalent response.

An art student’s persistence in approaching a blonde female teacher he desires is perceived as stalking, quickly becomes exactly that, and ends in violence. A female student with an entirely distorted idea of romance offers herself to her uninterested teacher so as to be liked, and is exploited, mocked and expelled.

The pull that cities exert on rural youth and their experience of city dwellers’ contempt, of unreliable and cruel employers, and the impossibility of making a living without an adequate education is a common theme.

These are the sort of stories that discourage those outside China from seeing the country as a monolithic economic and military threat, but rather as a collection of human beings faced with the same struggles to survive, to mate, to find housing, and to raise children as everyone else – something that should hardly need to be pointed out, but that tends to get lost in political rhetoric.

Woo’s stories are brisk and unforgivingly authentic. And there’s nothing more readable than the ring of truth.