Review | Horror, madness, escape: a Chinese-Australian’s memoir of living through Mao’s great famine and Red Guard terror

- Even as a kindergartener, Kwong could feel his family being shunned for the fact that they were well-educated teachers and therefore considered ‘bourgeois’

- His book about surviving childhood horrors and achieving the immigrant dream bears comparison with Frank McCourt’s visceral memoir Angela’s Ashes

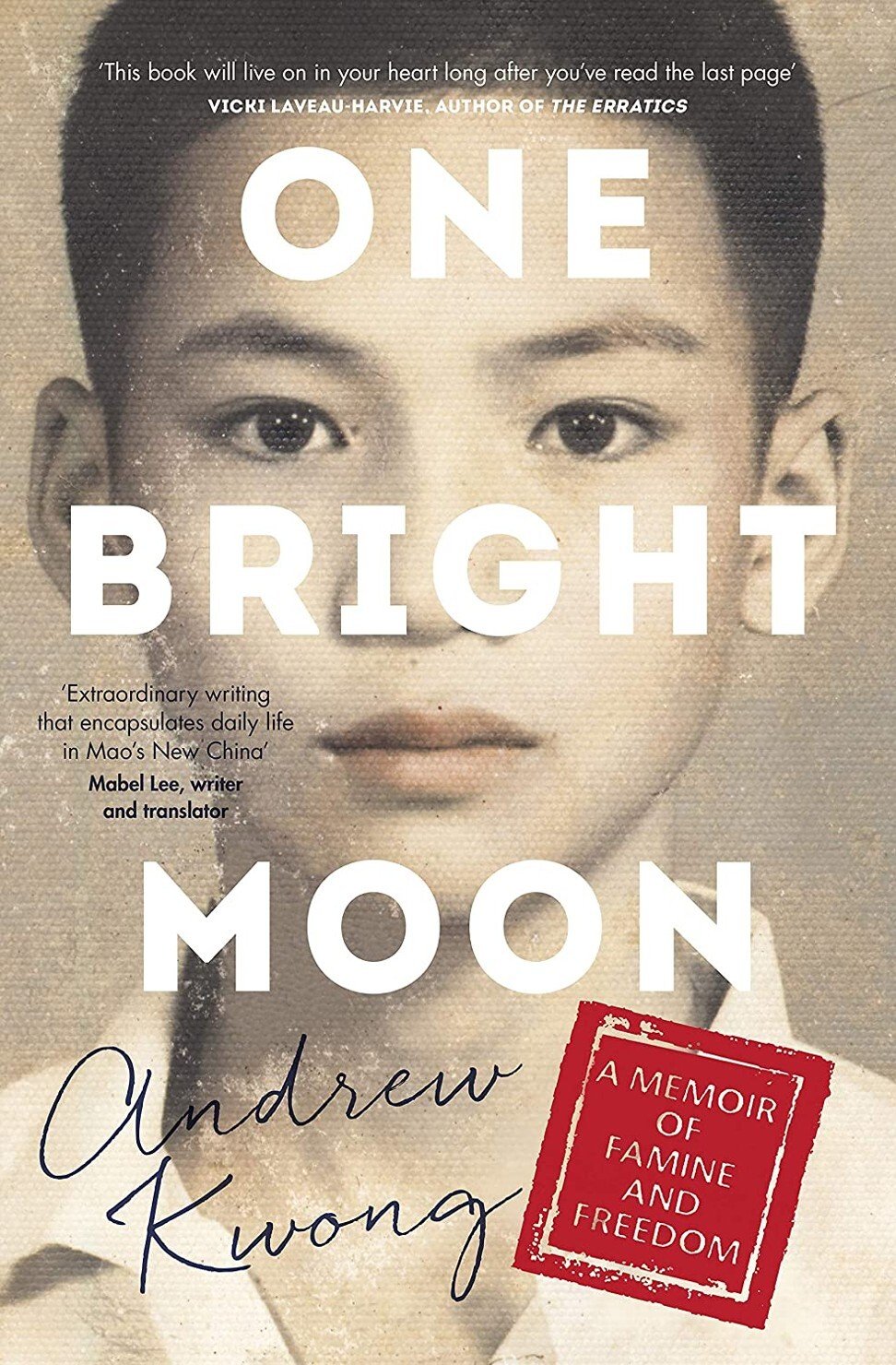

One Bright Moon by Andrew Kwong, HarperCollins. 5/5 stars

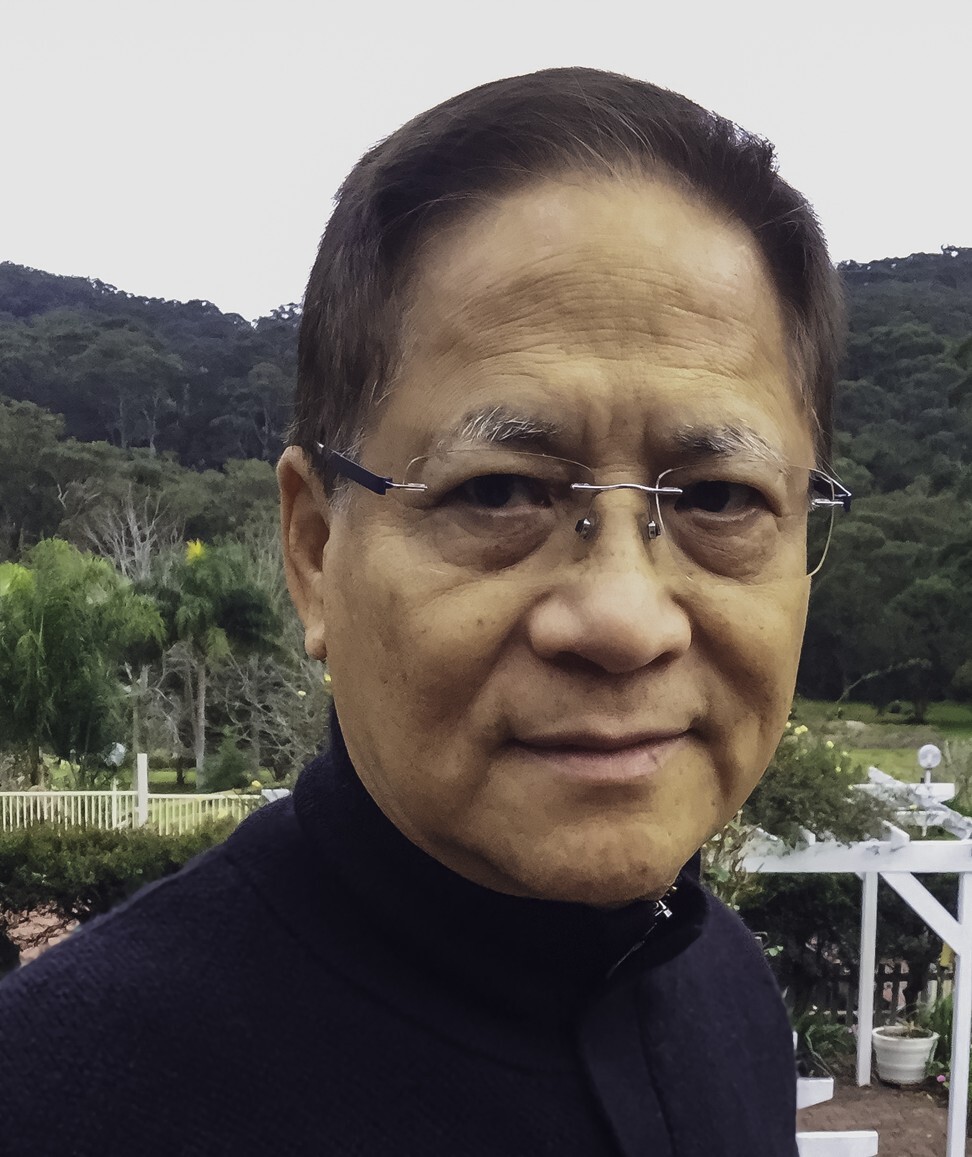

This powerful, sometimes brutal memoir, spanning half a century of Chinese history and migration, is the surprise debut of a family doctor who has published his first book at the age of nearly 70.

Andrew Kwong has lived a peaceful life on the outskirts of Sydney, Australia, but he could not shake memories of his traumatic childhood in China, his flight as a refugee to Hong Kong and his escape overseas.

So, for a few hours each morning before work, he would write his recollections, at first only to document them for his children and grandchildren. “I exhumed those confronting times I had long buried,” he writes.

The result is One Bright Moon, a work of startling clarity and humanity. In some ways, it is reminiscent of Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes (1996), another memoir about surviving an impoverished childhood and achieving the immigrant dream.

Kwong’s story begins in the 1950s in Shiqi, a town in Zhongshan, Guangdong province. Even as a kindergartener, he could feel his family being shunned for the fact that they were well-educated teachers and therefore considered “bourgeois” by the communists.

His parents, having seen the writing on the wall, sent the boy across the border to Hong Kong to seek safety with a grandmother. Kwong beautifully describes this period, using the simple but evocative language of a child. His grandmother, with her powdered face and lacquered hair, is every bit the Hong Kong lady, living in a Kowloon flat that smells of coffee and sandalwood incense.

Readers who grew up in Hong Kong will feel a pang of nostalgia as he describes, with wide-eyed wonder, life in the then-British colony: the sight of great trading ships in the harbour, the sounds of the foreign tongue called English, the taste of hot chocolate and buttered rolls.

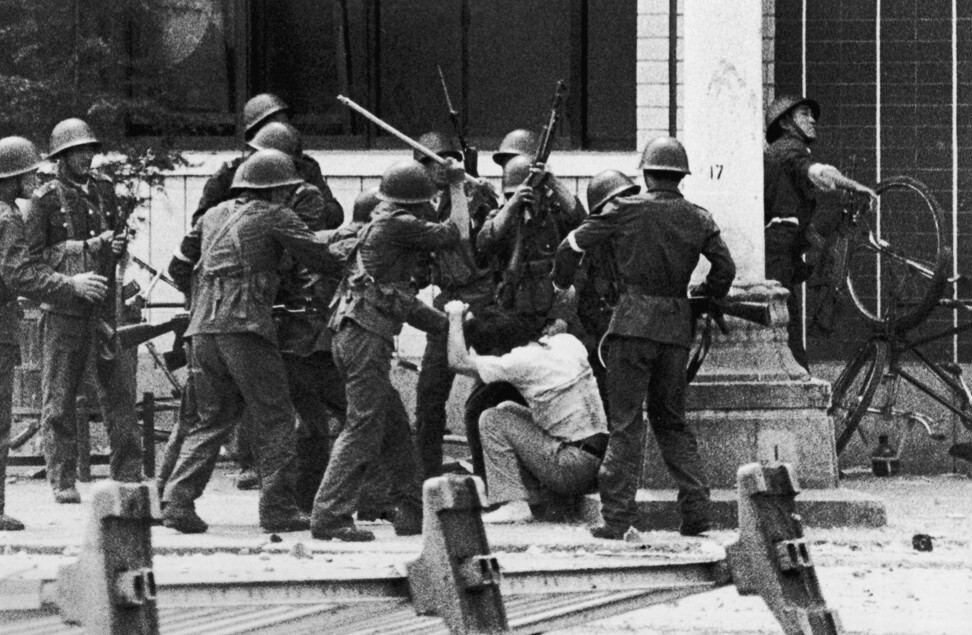

His life becomes a series of nightmares that leave him traumatised. The night after he returns, he witnesses his first execution. “I shook and gasped, and frantically looked for bullet holes on my body; I had to stop the bleeding,” he remembers. He watches as his father is arrested by a pimply-faced, obscenity-spewing Red Guard who storms into the family home.

Kwong learns to be suspicious of everyone and to censor his writing. One wrong word in a letter to his father, sentenced to 15 years of labour in Heilongjiang province, could get the family in more trouble. At the same time, the boy yearns for the trappings other children have, like the red scarves that would identify him as a true and loyal Chinese.

There are rays of sunlight in this otherwise dark narrative, such as when Kwong remembers flying kites, playing with his friends and watching ducks. He rejoices when his grandmother makes the rare trip to see him, bringing imported luxuries like Spam, condensed milk, arrowroot biscuits and bricks of brown sugar.

“My teenage brain found it hard to comprehend such a crazy world as the one in the 1960s, with those endless wars, conflicts, revolutions, invasions, starvations, killings, persecutions, imprisonments, murders, illicit drugs, prostitution.”

By the 60s, however, “famine had well and truly set in”. Kwong documents the physical horrors of starvation that he saw as a child: faces turned yellow, bellies swollen with gas, legs shrunk into sticks and oozing liquid.

“In the dark, people tripped over bodies and let out screams,” he writes of the corpses left in the streets. “We all kept our eyes wide open as we walked holding hands.” All anyone could think or dream about was making money and buying food.

Even the book’s rather poetic-sounding title has a cynical meaning. It comes from a quote from Kwong’s mother: “A bright moon will shine again one day, after the clouds disperse.” But she says these words just as she’s bribing a government official with cigarettes, in a desperate bid to find favour for her family.

At 13, Kwong begins the arduous task of getting first himself, and then his family, out of China. In the end, it is a process that will take decades.

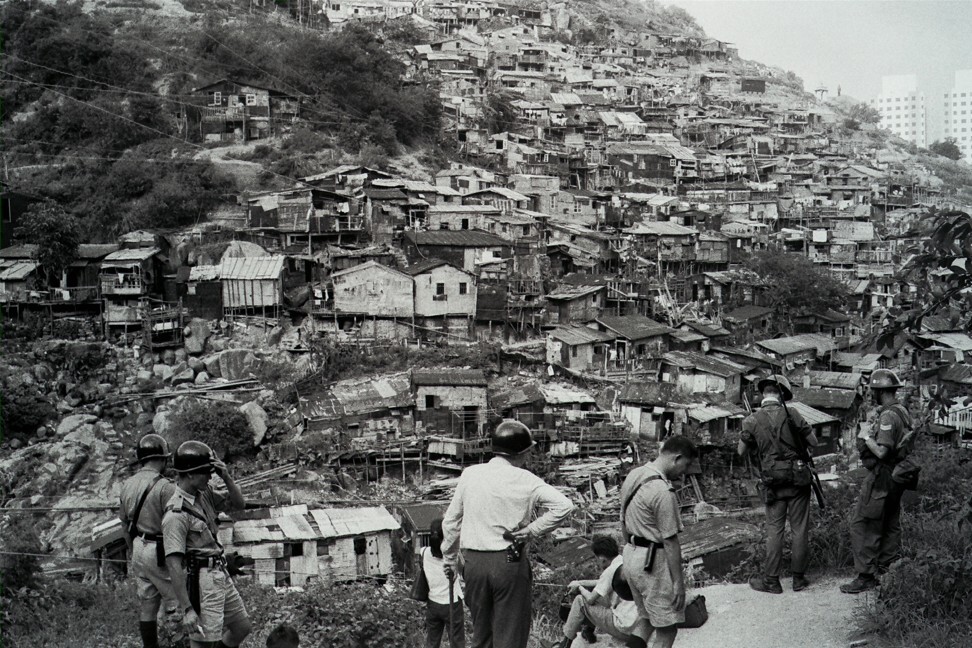

He first emerges in Macau as a dark-skinned, starving refugee, who did not even know his ABCs. He and his father finally settle in a shantytown in Hong Kong’s Diamond Hill, living in makeshift conditions, like the legions of other refugees from China who flooded into the colony.

Kwong grows up in Westernised Hong Kong, where European brothers teach him at La Salle College, and American troops listen to rock ’n’ roll on the streets. But he is tormented by not knowing the fate of his mother and siblings in China.

“My teenage brain found it hard to comprehend such a crazy world as the one in the 1960s, with those endless wars, conflicts, revolutions, invasions, starvations, killings, persecutions, imprisonments, murders, illicit drugs, prostitution,” he writes. “It was more complex than I’d ever imagined it could be.”

The second part of the book documents his emigration to Australia, where he attends medical school and marries a blue-eyed blonde he meets at a tennis court. Eventually, all of his family make it out, scattering like so many Chinese diaspora families to every corner of the globe.

Decades later, the Kwongs celebrate their first full family reunion in Washington. Life finally seems to have returned to some normality, until they turn on the news. It’s June 1989, and the crackdown in Tiananmen Square is sending China into turmoil once again.