Review | Forbidden Memory explores the role of Tibetan Red Guards in the Cultural Revolution

- The starting point for Tsering Woeser’s book was a trunk of photographs taken by her father in Tibet in the 1960s

- Based on more than 70 interviews, Woeser makes a powerful and nuanced argument against popular perceptions

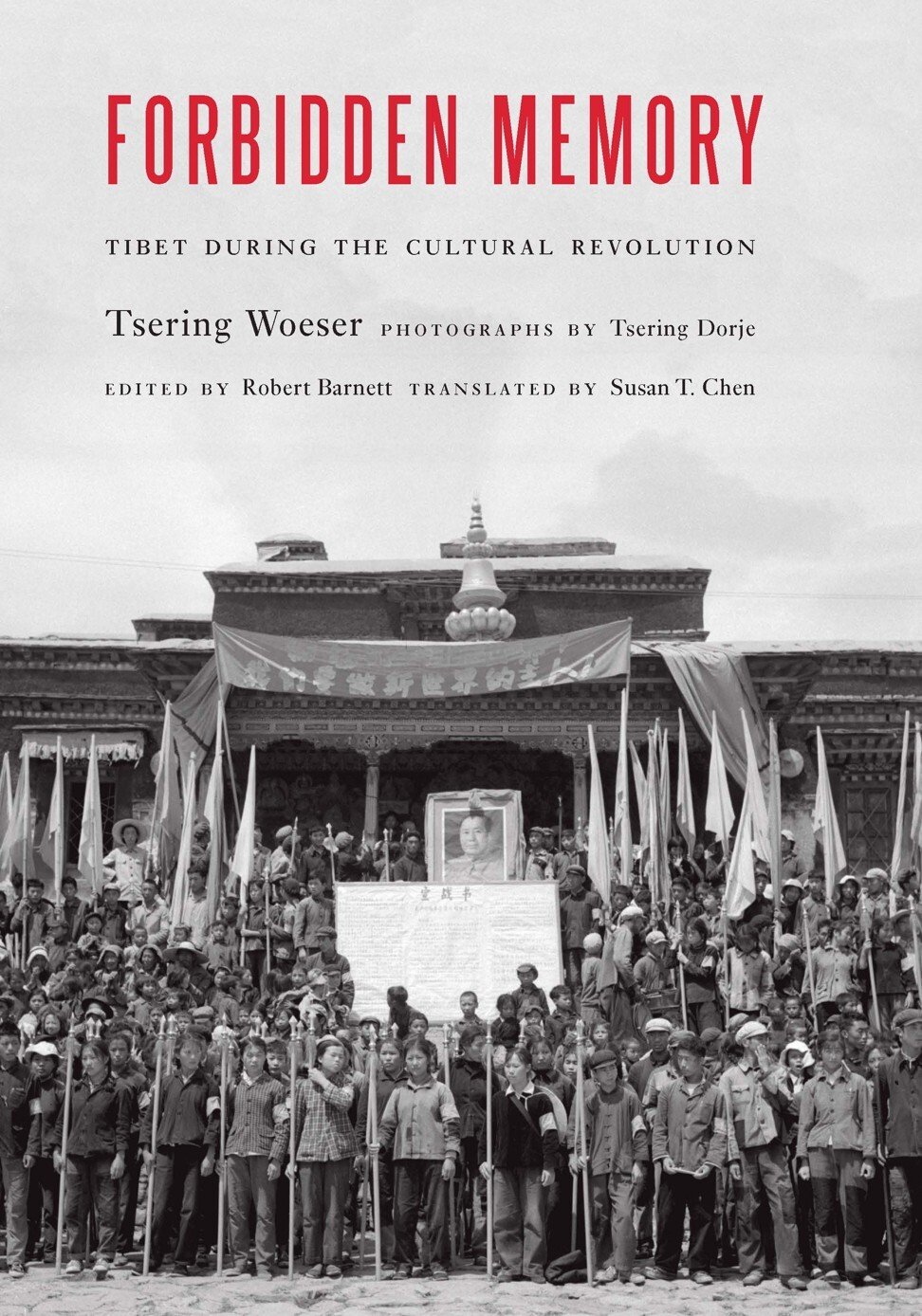

Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution

by Tsering Woeser

Potomac Books

4/5 stars

The Dalai Lama has called it “the most sacred temple” in Tibet. Located in the capital, Lhasa, and dating back to the seventh century, the Jokhang temple is a magnet for devout Tibetans who gather there every day to pray, prostrating themselves on the ground.

That is the disquieting belief of Tsering Woeser, a Tibetan intellectual, blogger and critic of Beijing’s Tibet policies. In her latest book, Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution, the Beijing resident dives into one of the most traumatic chapters in Chinese history, during which cultural relics were destroyed and political enemies were targeted for public abuse and humiliation.

The book is an updated English translation of Shajie, the title under which Woeser first published her work in Chinese, in Taiwan in 2006, the 40th anniversary of the start of the Cultural Revolution.

Based on interviews with more than 70 people who lived through the Cultural Revolution, Forbidden Memory contains hundreds of photographs from the period taken by Woeser’s father, Tsering Dorje, a People’s Liberation Army officer born to a Chinese father and Tibetan mother.

Woeser, who was born in 1966 just as the Cultural Revolution was beginning, inherited the photographs after her father died in 1991. But it wasn’t until 1999 that she thought of doing something with what she describes as “the most complete private record of these events yet to have come to light”. That year, she mailed the photographs to Wang Lixiong, a Chinese dissident whose book, Sky Burial: The Fate of Tibet (1998), she had just read.

“I had never met him, but I thought that rather than leave father’s photographs sitting in the trunk, it might not be a bad idea to entrust them to a scholar willing to study Tibet in a balanced way,” Woeser writes.

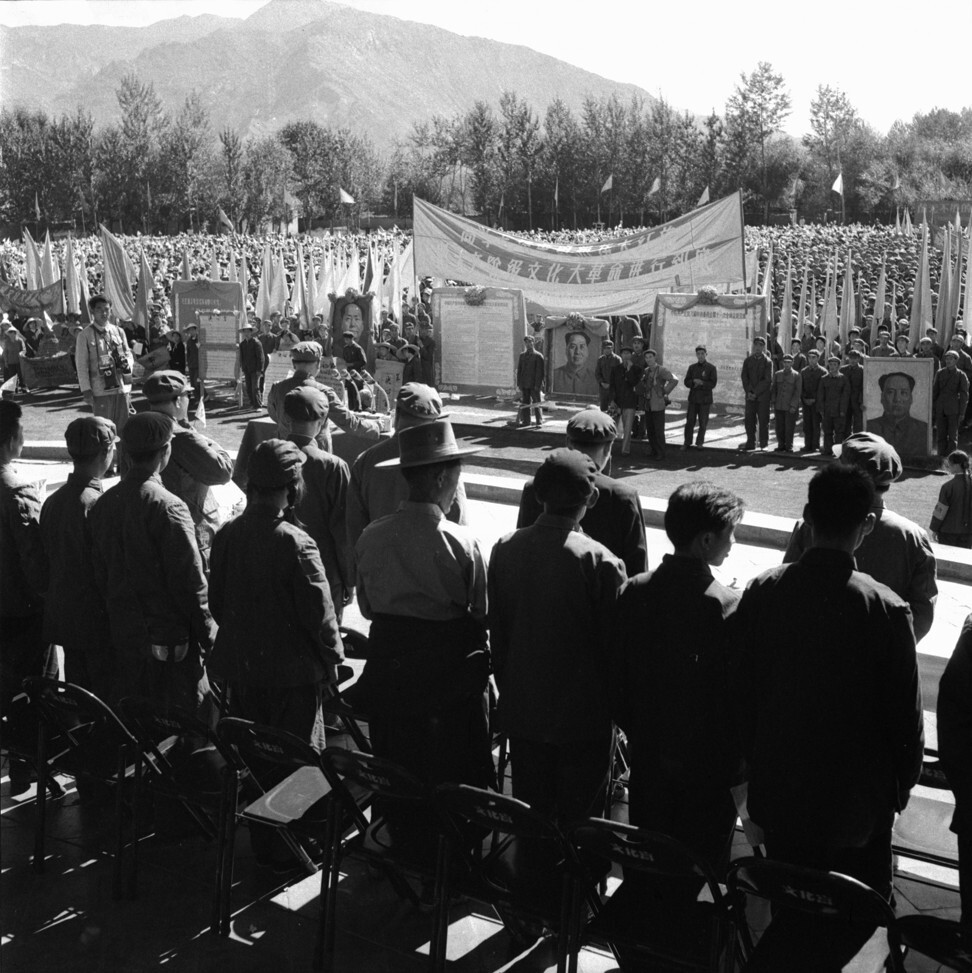

The photographs in Woeser’s book depict everything from the destruction of religious relics, “struggle sessions” (a form of public humiliation and torture) and militia training to rallies, parades and manual labour. Just about every image captured by Woeser’s father is a precious historical resource: “until Woeser released this book there were no images of that period from Tibet in public circulation, either in Tibet or elsewhere in the world”, writes Robert Barnett, a British scholar of Tibetan performance art and media, in the book’s introduction.

Many of the photographs attest to the vandalism and violence of the revolution. When Red Guard cadres ransacked the Jokhang in 1966, for example, Woeser’s father photographed a young Tibetan woman hacking off the golden edging of the temple’s roof with a harrow.

The woman, like her compatriots, was following one of the revolution’s central tenets: denounce the “four olds” – old society, old culture, old traditions and old habits. Woeser wonders why the woman appeared to believe that “turning the past to ruins would give birth to a bright new world”. Her question, like many of the book’s 345 images, challenges readers “to try to understand the ideological constructions of the time that made such actions seem natural and even necessary to so many participants, both the rulers and the ruled”, writes Barnett.

In lucid, engaging prose interspersed with her own insights, Woeser highlights how the Cultural Revolution shaped the contours of Tibet’s negotiation with communist China. Her account is a powerful, nuanced argument against the popular perception that Tibetans strongly resisted Beijing’s secularisation and sinicising policies.

Woeser is intrigued by the possibility that many Tibetans became Red Guards, attracted to new ideas and revolutionary fervour. At the same time, she writes, “the atmosphere of red fear created by the authoritarian regime” probably left them no choice but to be “sucked against their will into the string ride of radicalism”.

A close look at a photograph depicting the installation of a Mao portrait on the rooftop of the Jokhang illustrates the author’s viewpoint. The image captures crowds gathered to watch uniformed Red Guards place the portrait and a Chinese flag in a spot previously occupied by the Wheel of Dharma, a revered Buddhist symbol.

“Tibetans would not easily abandon their gods,” Woeser writes. But the occupation and the Dalai Lama’s 1959 exile, “seem to have shown that the new god was so powerful that the ancient gods of the land had been defeated”.

She adds: “Tibetans can be said to have been in shock, stunned by everything that was unfolding before their eyes, so that when the Cultural Revolution took place, they accepted the new reality.”