Review | Julie Yip-Williams’ memoir Unwinding of the Miracle reveals how to live, and die, with dignity

- From her start as a blind Vietnamese refugee to realising the American dream, the lawyer’s life and untimely death at 42 is laid bare

- Author documents the ugly emotions summoned by cancer and the surprising joys that dying can bring

The Unwinding of the Miracle

by Julie Yip-Williams

Random House

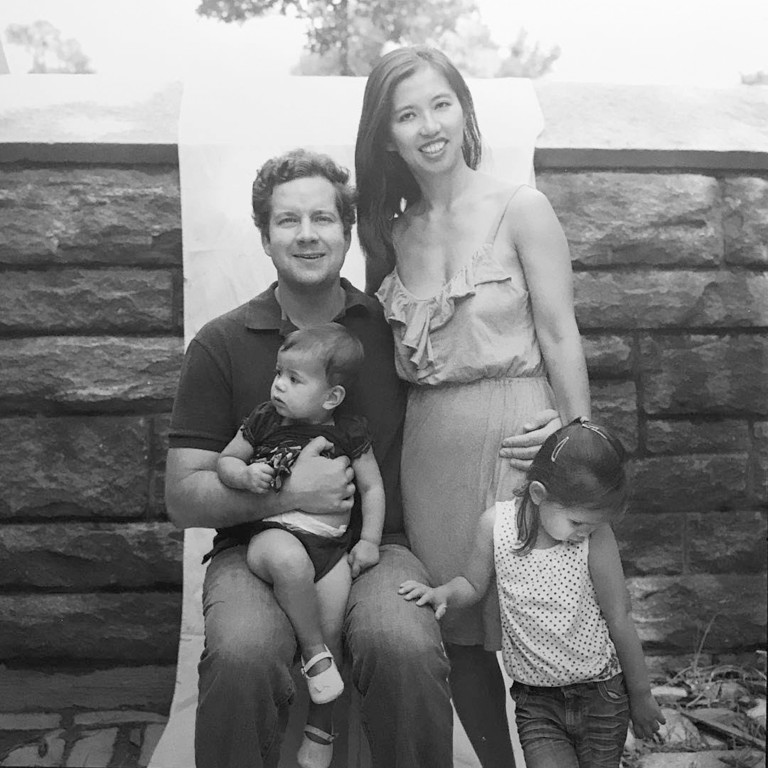

Julie Yip-Williams’ memoir about dying from cancer is as brutally honest as it is beautifully written. With the typical frankness of a Chinese mother, she lays out everything, from the worry and heartbreak of leaving her two children behind to graphic descriptions of bodily functions and medical procedures. The Unwinding of the Miracle is written as a posthumous letter to her husband and daughters, Mia and Isabelle. But, really, it is a letter to us all.

“This story begins at the ending. Which means that if you are here, then I am not. But it’s okay. My life was good and my life was complete,” she writes in the prologue.

“Dying has taught me a great deal about living.”

A blind child refugee from Vietnam, Yip-Williams achieved a life she never could have imagined. By her 30s, she had become an Ivy League-educated lawyer with a New York apartment, an American husband and two bright little girls.

Everything changed in 2013, when the young mother was sent to an emergency room with abdominal pain. It turned out to be stage four colon cancer, a disease that would kill her in 2018, at the age of 42.

Soon after her diagnosis, Yip-Williams started a blog that would change the way many talk about cancer. She documented the gruesome aspects of the disease and the complex, ugly emotions that accompany it. But she also shared the unexpected happiness she discovered in her family, her city and herself.

She wrote about the daily joys of watching her daughters, shared her recipes and detailed her crush on tennis star Roger Federer. But she also described the pain of not being able to eat solid food for four days while drooling over cookery shows on her iPad.

The “miracle” in the book’s title refers to the fact that Yip-Williams made it at all.

The first chapter, “Death Part One”, is set in 1976, when Yip Lijiang was born poor and blind in war-ravaged Vietnam. Her Chinese grandmother had decided that what was best for the disabled infant was to have a herbalist put her to “sleep forever”. Having been given her first death sentence at two months old, Yip was spared by an ethical herbalist and the intervention of a kindly great-grandmother. Two years later, her life was put at risk once more, when her family escaped Vietnam on a leaky, crowded boat across open seas to a Hong Kong refugee camp.

When the adult Yip-Williams learned of the low survival rate for her type of cancer – less than 15 per cent – she drew on the strength of her childhood background to take the bad news in her stride. “My very existence on this planet is evidence of how little numbers matter to me,” she wrote.

If the “odds” were to be believed, she would not have survived infancy, much less a journey to Hong Kong that was the death of grown men. She never would have made it to America, where an eye surgeon partially restored her sight. She wouldn’t have been literate, much less a graduate of the elite Williams College and Harvard Law School. She would not have travelled the world solo.

The second chapter, “Life”, jumps to 2017, when Yip-Williams was pragmatically preparing for her own demise while writing a detailed “to-do” list for her husband regarding school fees, dental care and the cleaning of air filters. Yip-Williams was a tiger mother to the end. She oversaw the expansion of their flat, purchased an SUV and acquired a puppy for the kids. She made her brother do “one last trip to Costco together, because that’s what Chinese siblings who love deals do together”. She even imagined a future partner for her husband, whom she had jokingly nicknamed Slutty Second Wife.

But even Yip-Williams admitted that making lists and arranging the kitchen was low-hanging fruit – a way to assure herself that everything would be OK after she was gone. The real challenge was somehow to ease her daughters’ pain – to create this book so they would remember who she was, understand the reality of what killed her and develop the tools to move on to happy, fruitful lives.

Some books about life and death read like Hallmark get-well cards, filled with comforting platitudes and messages of hope. Yip-Williams takes the Hallmark card and sets it on fire

To say that this book is a dose of tough love is an understatement. Yip-Williams’ message to her daughters is that life is not fair and it is unfair to expect otherwise. Much is decided outside our control, no matter how hard we try, so the living should make the most of the time we have. And her daughters should draw on the strength of surviving tragedy in their childhood, much as Yip-Williams once did herself.

The beauty of the writing comes from the author’s keen eye for the details of daily life. Of a trip to Chinatown to get a herbal medical treatment, she writes: “Amid the open-air markets of fruits and vegetables and smelly fish and the restaurants with the roasted ducks and chickens hanging in their windows sits the uncrowded herbal pharmacy.”

But the Chinatown herbalist failed her in the end, as did the many rounds of chemotherapy, surgery, clinical trials and alternative treatments.

Some books about life and death read like Hallmark get-well cards, filled with comforting platitudes and messages of hope. Yip-Williams takes the Hallmark card and sets it on fire. One of the stated aims of her memoir is “to depict the dark side of cancer and debunk the overly sweet, pink-ribbon facade of positivity and fanciful hope and rah-rah-rah nonsense”.

She describes the confusion and exhaustion experienced by a patient in the modern medical system. Even as an intelligent, well-educated professional, she was confounded by CEA numbers, the FOLFOX regimen, HIPEC surgery and PET scans versus MRIs versus CT scans. She remembered signing a consent form about “the possibility that my bowels could not be put back in my body, in which case I would have an ostomy or colostomy or some other words that ended with ‘omy’.” There is a good dose of gallows humour. “I’m losing parts at a pretty good clip now,” she quipped when the cancer spread to her ovaries and they had to be removed.

She disliked the military-inspired language used to describe cancer: that patients are “warriors” who are “fighting a battle”. Instead, she compared cancer to a force of nature such as a hurricane. “There comes a time when one must admit that powerlessness and evacuate,” she wrote.

This book poses a difficult question: who is braver, the cancer patient who tries every gruelling medical intervention or the one who stops treatment and faces her mortality, “who walks away, choosing to feel good for as long as she can”? Why do we assume a longer life is a better one?

Yip-Williams saw her life as a miracle that kept unwinding – but miracles don’t last forever. “And when the time comes, we control the terms of our surrender.”

She died not in a hospital but at home, surrounded by family, as she had wished. She passed away in the same bedroom where she and her husband conceived their children, with its sunny window and view of the Statue of Liberty. Her ashes were to be scattered in the Pacific, “the ocean that lies between the land mass where I was born and the one where I lived my improbable life”.

She had achieved her goal “to die well, to die at peace, without regret for the life I have lived, proud and satisfied”.

I can’t recall being more haunted by a book, perhaps because of what I have in common with Yip-Williams. We both grew up as studious schoolgirls, in Chinese immigrant families in America. We are both wives and mothers, with two daughters of similar age. We share a love of home cooking, big-city life and detailed to-do lists. She came so alive in these pages that I felt she had become a friend. Only she is gone and I am not.

The day after I finished this book, I went to a carnival in Central, Hong Kong, with my daughters. All the normal annoyances – the pricey tickets, crowds, noise and temper tantrums – fell away into a deep gratitude. Throughout the Lunar New Year holiday, between boisterous family meals and fun activities with my kids, I thought about Yip-Williams’ message: “Live while you live, my friends.”