Review | Eileen Chang’s life in wartime Hong Kong and Shanghai laid bare in autobiographical novel

Translated into English for the first time, Little Reunions recounts how familial strife and misguided passion endanger a writer’s struggle for modernity in time of war

Little Reunions

by Eileen Chang

New York Review Books

4/5 stars

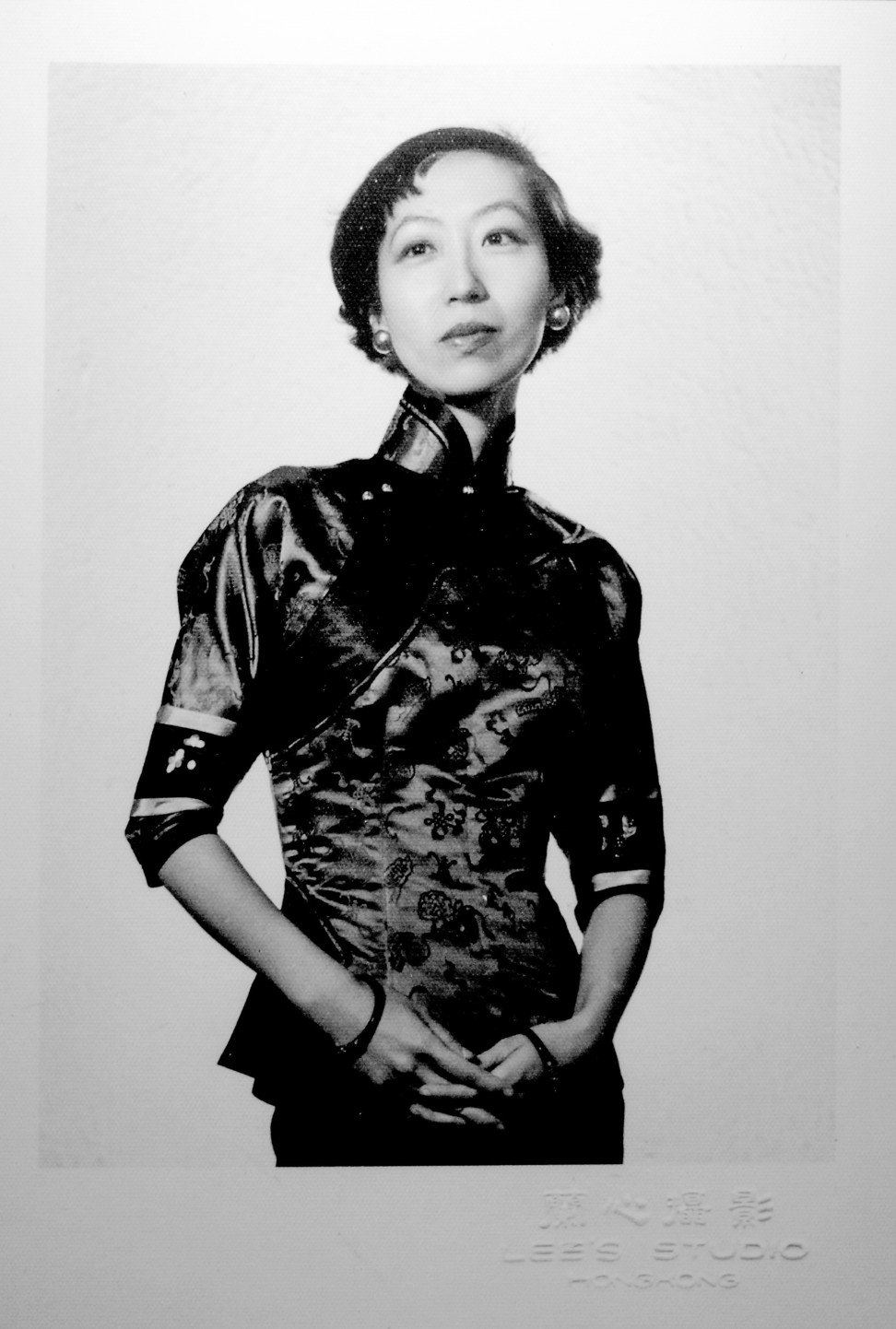

More than 20 years after she died alone in her Los Angeles apartment in 1995, Shanghai-born Eileen Chang has a cult following that started in Hong Kong and Taiwan, spread to the mainland and then the English-speaking world.

Her international reputation is likely to be further cemented by the English-language publication of Little Reunions, which was written in 1976 and first hit shelves in Chinese in 2009. Translated masterfully by Jane Weizhen Pan and Martin Merz, it is published by New York Review Books, which also boasts other Chang works Love in a Fallen City and Naked Earth in its catalogue.

Little Reunions is Chang’s most autobiographical work, and probably the best for interpreting how she viewed her own life. Julie Sheng, the novel’s heroine, is more than loosely based on Chang and the upheavals she experienced before leaving her home in Hong Kong for the United States in 1955.

Like Chang herself, Julie is born into a complicated family in Shanghai and struggles with the social and moral implications of China’s transition from imperial rule to modernity. Also like Chang, Julie goes to study in Hong Kong, but her life there is disrupted by the Japanese invasion in 1941.

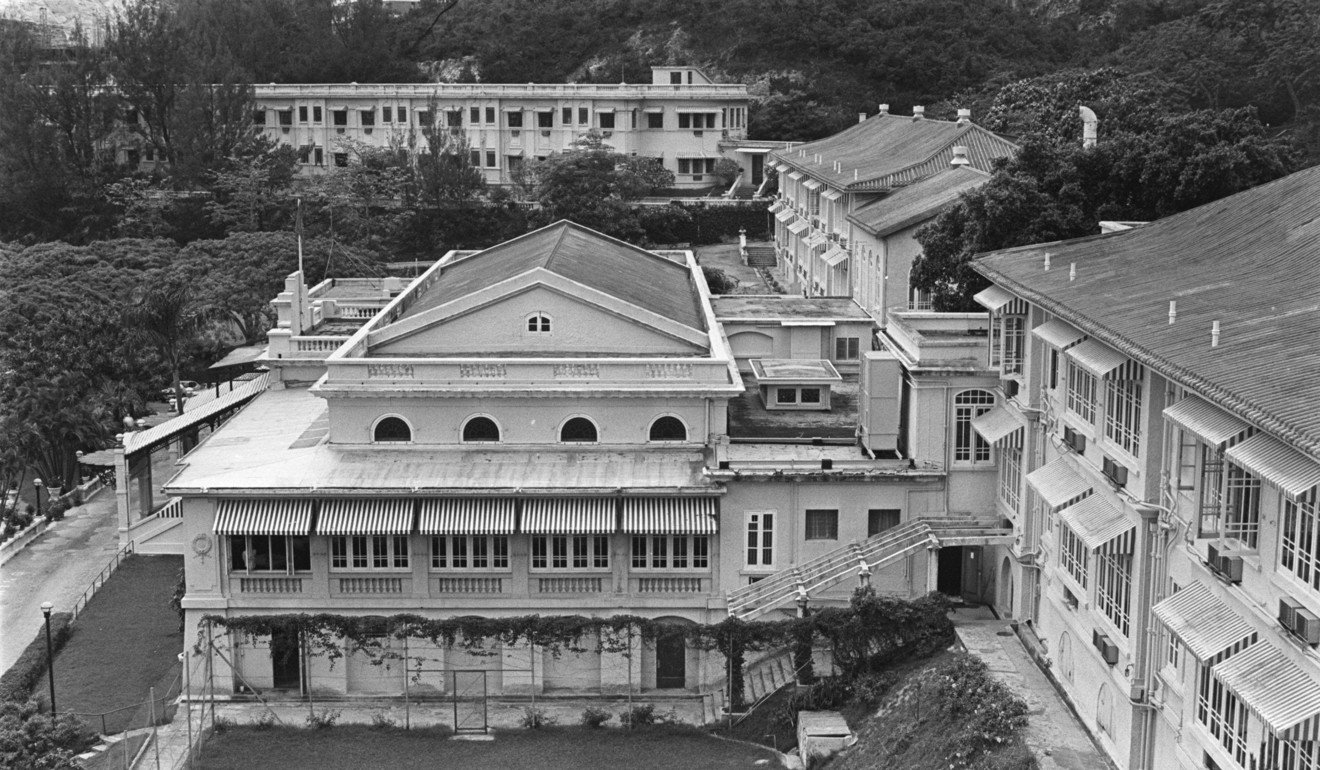

Although only the first two chapters of the novel are set in Hong Kong, they offer a remarkable glimpse of life in the city at that time. Not only are we offered vivid descriptions of bombings and the difficulties of the occupation, but we also learn that mainlanders were already facing sidelong glances when they spoke Mandarin in public. And the scenes set at the old Repulse Bay Hotel will make many readers ache for that landmark, demolished in 1982.

Despite the war, Chang’s Hong Kong is a cosmopolitan place where greater freedom, when compared with the mainland’s stifling morality and intellectual constraints, allows free-thinking individuals to blossom.

Again like Chang, Julie returns to Shanghai, with the war raging across China, and lives through the Japanese defeat, the civil war and the Communist takeover. Julie’s reactions to these momentous events closely follow those of the writer, as does Julie’s growing estrangement from her family, her complicated love life and her budding career as a writer.

Julie also has a bad relationship with her father, a patriarchal figure who reluctantly divorces his rebelliously modern wife and takes a concubine, which also echoes Chang’s experiences. The father then locks up Julie after she has a fight with the new mistress of the house. Imprisonment by her father and her subsequent escape left Chang scarred and she often returned to this experience in her writing.

Essentially, Little Reunions traces the life of a woman who starts out full of potential in Hong Kong, only to see her aspirations thwarted by war, and to suffer a painful, doomed passion for a man too enamoured with himself to be kept as a husband for more than a few years.

While it is not one of Chang’s easiest works (the plot is less linear than, say, her more fast-paced Half a Lifelong Romance and Lust, Caution, both of which made it to the big screen), Little Reunions is a rewarding read.

The many characters making brief appearances mean the who’s who list at the end of the volume is a lifesaver, and readers will be forgiven for occasionally wondering who exactly is doing what. But the main protagonists – Julie herself, her fabulously histrionic mother, her secretive aunt Judy and Shao Chih-yung, her infuriatingly self-absorbed and disloyal first husband, whom she loves against all reason – are sketched with clarity and Chang’s trademark grace.

Other distinctive Chang traits in the novel include the use of many simultaneous layers that add depth to the narration, and while historical turmoil influences every decision made by Julie, Chang never weighs the book down with lengthy descriptions of the political situation. The Japanese invasion, the civil war and the Communist victory are like pictures hanging on the wall – permanent fixtures in the background.

Chang came from a once-wealthy family closely associated with the imperial era: her paternal grandfather, Zhang Peilun, was a 19th-century naval commander and government official, and her father a small-time official who seemed less than happy about the republican era.

The writer kept publishing, and enjoying her growing fame, under the Japanese occupation and never showed any enthusiasm for the Communists, displaying outright hostility to any political decrees on literature and social life. In Little Reunions, for example, the arrival of Communist China is illustrated only by some characters losing their jobs or having to go into hiding, while the more entertaining press gets shut down or “reformed”.

For a woman who adored fashion, make-up and interior design, the revolutionary sobriety imposed by Mao Zedong’s victory must have been stifling, if not downright offensive. Chang’s absolute modernity, and her dislike for convention and political expediency, are partly responsible for the glacial speed at which the mainland has embraced her writing: she was a Chinese writer, but a bilingual one, writing in both Chinese and English.

Most of all, though, on the mainland she remains somewhat infamous for her marriage to the writer Hu Lancheng, a Japanese collaborator active in the occupying force’s propaganda ministry. While their relationship was the source of much suffering for Chang, the fact that she was married to a collaborator made her a politically sensitive figure.

Times have changed, however, and Chang is now starting to be recognised as the important literary figure that she is.