Profile | She’s worked with the Jackson family, and Jacky Cheung: for Roxanne Seeman, songwriting is ‘like a passport’

- New Yorker Roxanne Seeman has been penning hits for 50 years; China is her current focus. She’s writing songs for Cantopop and Mandopop stars, films and TV

- She reflects on how she ‘learned about artists around the world by travelling’, her song for the Jackson family and the one thing she is ‘super proud’ of

“Songwriting is like a passport. I learned about artists around the world by travelling,” says veteran lyricist Roxanne Seeman on a video call from her cosy Santa Monica, California, apartment in the United States.

“The fact that I could make a life out of doing this – I pinch myself.”

I met Seeman last year, at the wrap party of a Universal Music songwriting camp in Hong Kong. She was in the city for six weeks, mingling with regional talent and collaborating with her mentee, Vince Fansheng Gao, a musician from Shenzhen in southern China.

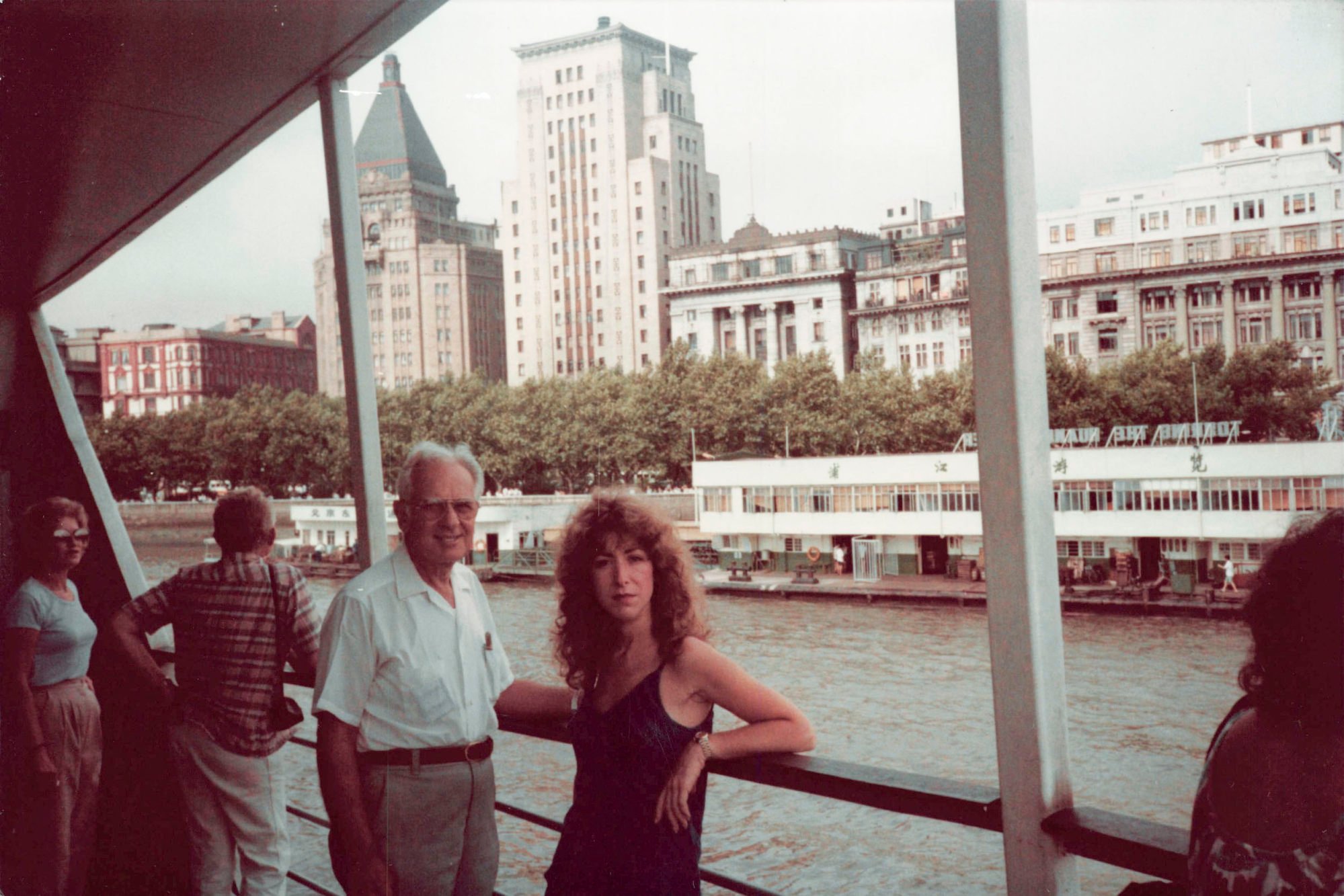

A decade after that historic moment, and three years after the two countries established full diplomatic relations, Seeman and her parents took a three-week trip to East Asia.

“The funny thing was I could speak a little, so every day when I was ordering food – which was a lot of pork and string beans – I could ask in Chinese,” says Seeman, giggling. “I happen to love eggplants, and when I asked for qiézi, the locals loved that.”

The song also marked the start of her 17-year partnership with late singer-songwriter Billie Hughes.

The two made magic together for Bette Midler, The Sisters of Mercy, and Japanese pop duo Wink, to name a few, cross-pollinating pop, jazz, soul, R&B, soft rock and more. Their song “Welcome to the Edge” was nominated for an Emmy.

“It was mind-boggling, sitting there at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas and having your song be the theme song of this, with the whole family and all these artists up there singing it.”

After Hughes died, aged 50, from a heart attack in 1998, Seeman continued the work, and in 2005, she wrote the jazz number “So Blue” with Turkish-American composer Arif Mardin, which would be recorded by Queen of Funk Chaka Khan, with David Sanborn on the saxophone.

“Songwriting is an expression of what you are emotionally experiencing as a human being from day to day,” she says, “because every day is an emotional experience of something – the person you’re spending time with, the circumstances of what you’re doing, the ride you’re taking in life, or just waking up in the morning and anticipating what the day is going to bring.”

“Tuason wrote me back right away. The next day, we ended up on the phone and for two hours he went through my songs – one by one. He would say, ‘This will be good for Cantonese’; ‘This is going to be good for Mandarin’; ‘This isn’t going to work at all,’” she says.

Seeman tailor-made five of the 10 tracks on the album, including the big-band swing number “Double Trouble”, which was rearranged and given a new production and choreography in the ongoing “Jacky Cheung 60+ Concert Tour”.

Seeman is now working with 24-year-old Gao, who has just graduated from the University of Southern California with a master’s degree in music management.

They have written soundtracks for multiple Chinese motion pictures and television series, including To Us From Us, which is scheduled to be released later this year.

R&B singer Tia Ray: my music isn’t ‘fast food’, it takes time to understand

“To be an American getting in on a local Chinese production – I’m super proud of that,” she says, “because that’s harder to get into than, say, Asian- or Chinese-themed US productions, for which I could pitch my songs through a music supervisor at a film studio that markets movies worldwide.

“To be able to write something for a local production – something that caters to the Chinese audience – puts me closer to the heart, closer to the heartbeat of the people.

“I don’t think you can buy that.”