How Jackie Chan’s action comedy Rumble in the Bronx opened ‘the golden door to the West’ for the Hong Kong star, launching his Hollywood career

- Jackie Chan tried to crack America in the 1980s with The Cannonball Run and The Big Brawl, but it was his 1995 film that launched him on the international stage

- It featured Anita Mui, but through graceful fight scenes and stunts, Chan emerged the star of the show, and proved that he did what he did ‘better than anybody’

“Don’t let the situation change you,” says Jackie Chan’s Hong Kong cop midway through Rumble in the Bronx, the riotous action comedy from 1995. “You have to change it.”

When it came to cracking America, it was advice Chan would learn to heed himself. His first effort, 1980’s The Big Brawl, lacked directorial dynamism.

The turning point came with Rumble in the Bronx, a joint venture between Hong Kong’s Golden Harvest and Hollywood’s New Line Pictures, directed by Stanley Tong Kwai-lai from a script by Edward Tang and Fibe Ma.

The key was not letting the situation change Chan’s star persona, just working out how to transplant it to America.

The film begins with Keung (Chan) visiting his Uncle Bill (Bill Tung), who’s living the immigrant dream of assimilation in New York.

When Keung arrives, Bill tries to impress upon him the importance of fitting in. Speak English, he advises, “You’re in the USA now.” In reality, most of the dialogue was dubbed, leading to some erratic line readings.

They’re not the only eccentricities. Seen through Tong’s viewfinder, America is a colourful, lawless place, somewhere from the movies rather than a map.

Beyond Bruce Lee: the rise of Hong Kong cinema during the 1970s

Keung, his love interest, Nancy (Françoise Yip Fong-wa), and her little brother, Danny (Morgan Lam), are menaced by a gang of bizarrely dressed thugs led by Tony (Marc Akerstream) who ride motorbikes and quad bikes like extras from a Mad Max film.

Later, they cross paths with machine-gun-toting diamond thieves working for big boss White Tiger (Kris Lord). The climax, in which the villains commandeer a hovercraft with Keung water-skiing behind, then proceed to tear through the city, has to be seen to be believed.

For a visual summary of the film’s giddy charms, look no further than the moment a van drops a load of colourful balls off a roof, and they bounce joyfully – if randomly – through the streets.

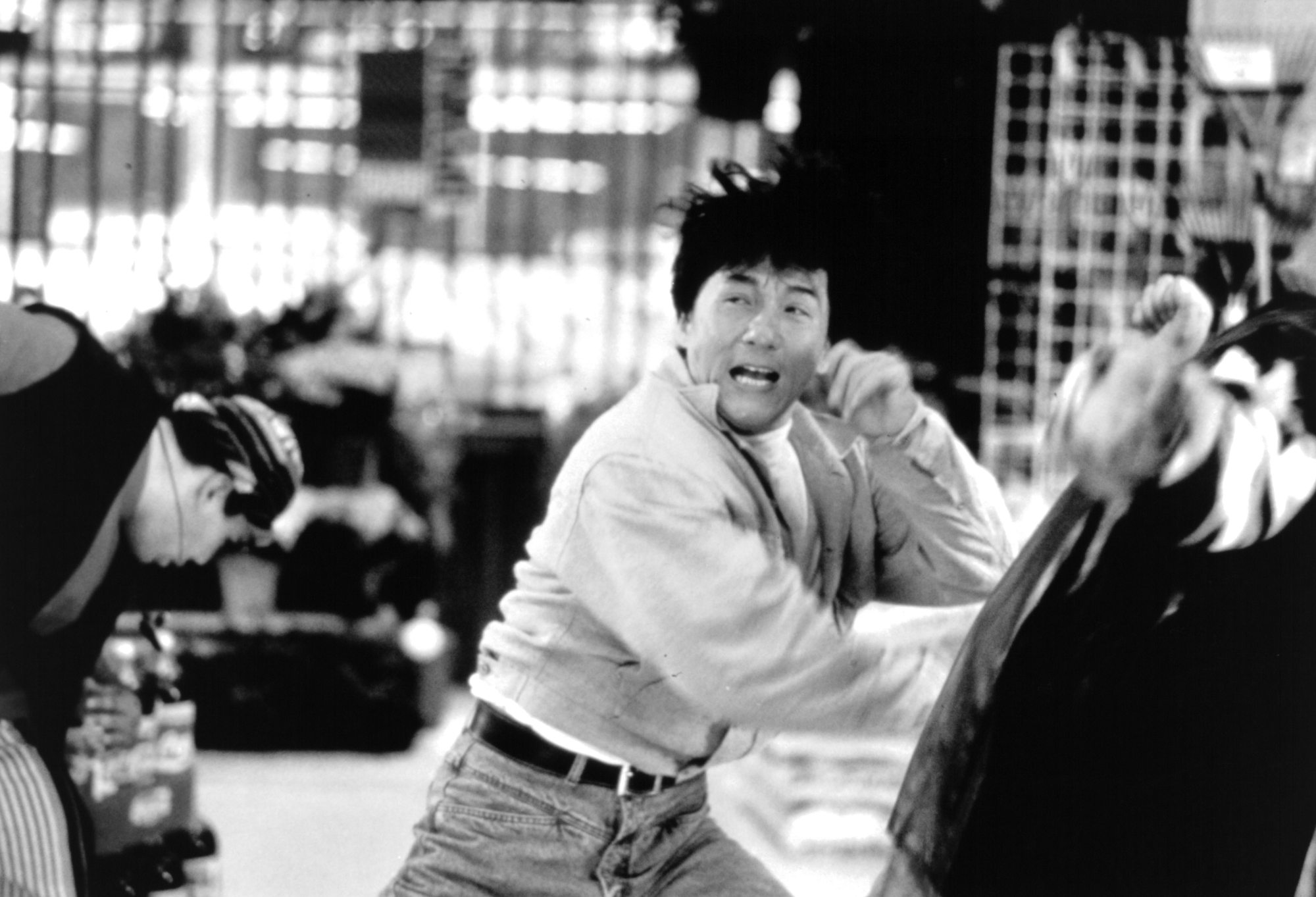

But the star of the show is undoubtedly Chan, his talents gradually revealed throughout the film.

One moment he’s casually walking on his hands, the next he’s jumping from a multistorey car park to the next building – an incredible 8.5 metre (30ft) leap Chan performed himself, without a harness.

When Martial Art World asked him if he knew he could make it, he admitted, “It’s a guess.”

Of the many, many fights, the highlight is an inventive set-to in the gang’s clubhouse, which encompasses a pool table, a chandelier, a pinball machine, a ski and several fridges, which Chan spotted in a flea market and thought he could use on-screen.

But like the greatest musical and silent film stars, he always gives the impression he’s making things up as he goes along.

As veteran critic Roger Ebert wrote in the Chicago Tribune: “Any attempt to defend this movie on rational grounds is futile […]

“The whole point is Jackie Chan – and, like Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, he does what he does better than anybody.

“There is a physical confidence, a grace, an elegance to the way he moves. There is humour to the choreography of the fights […] He’s having fun. If we allow ourselves to get in the right frame of mind, so are we.”

America might not have known it, but Chan had been training for this his whole life, with roles that underlined his ordinary-guy persona while emphasising his extraordinary abilities.

The film ends with a blooper reel showing him breaking his ankle jumping onto the hovercraft, then finishing the film in a plaster cast. Somehow, he still manages to smile for the camera and give the audience a thumbs up.

He had reason to be happy. Rumble in the Bronx would go on to become the highest-grossing film released in Hong Kong, winning a Hong Kong Film Award for best action direction.

It also broke box office records in China and was named one of the year’s top 20 R-rated movies in the United States, launching his Hollywood career.

“And just like that,” Chan wrote, “I was a big star in America after 15 years of trying.” Or, in other words, he’d changed the situation without changing himself.