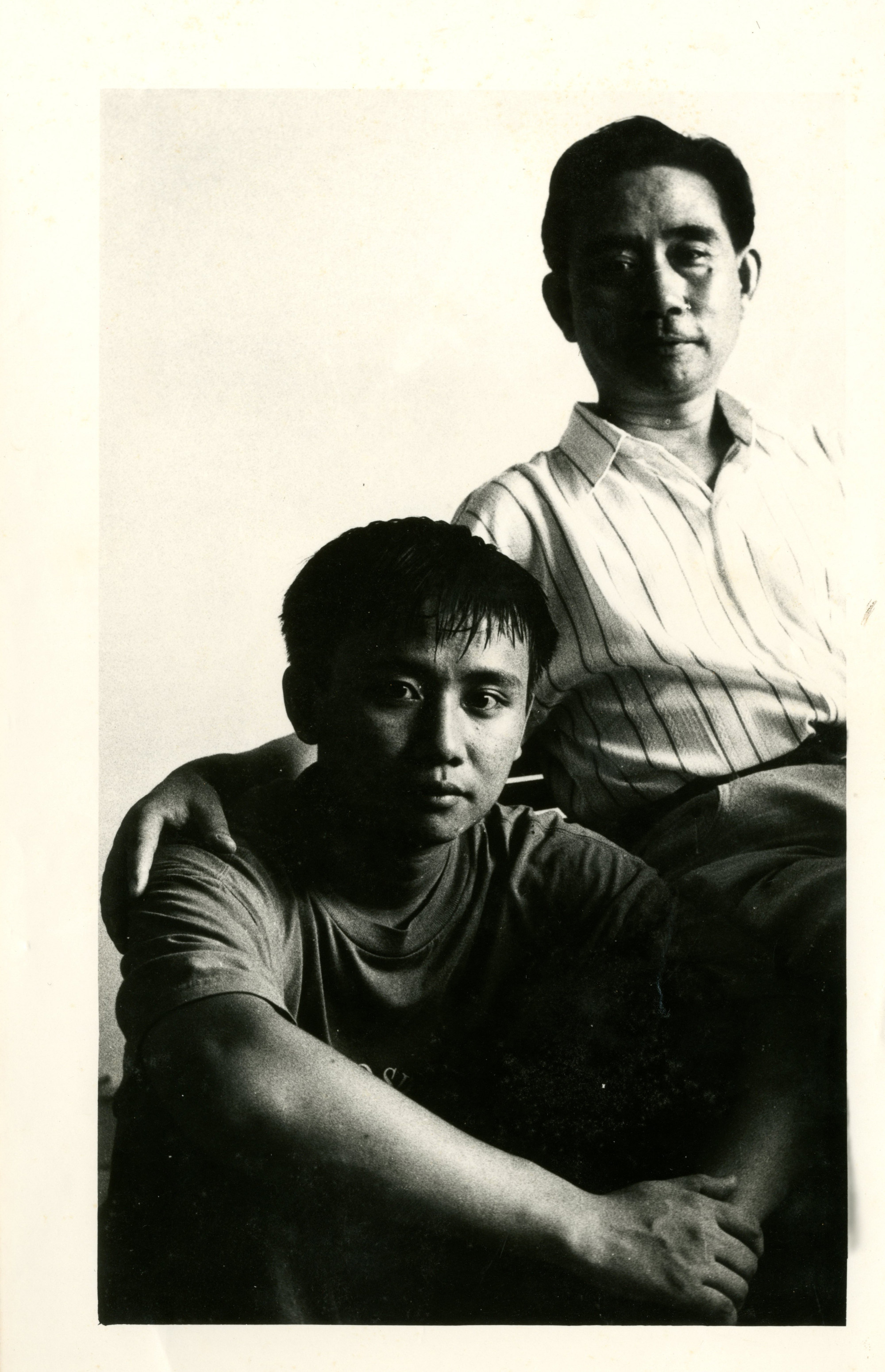

Profile | Pi Li, head of art at Tai Kwun in Hong Kong, on studying fine arts in Beijing, taking a film to the Cannes festival, and becoming ‘a Hongkonger’

- Tai Kwun’s head of art tells Kate Whitehead about inheriting his father’s love for modern art and pursuing his passion from Beijing to Glasgow and Hong Kong

- He talks about studying at Beijing’s CAFA fine arts academy, walking the red carpet at Cannes, and helping get ‘world class’ M+ in Hong Kong up and running

My father was a worker through the Cultural Revolution and when it ended, he went to the Hubei Academy of Fine Arts at the age of 40. He stayed on at the academy and became a professor and was among the first critics of avant-garde art in China. My mother was a doctor.

I was born in Wuhan in 1974 and was an only child. Wuhan is surrounded by mountains and is one of the hottest places in China. As a child, in the summer, we slept outside on the street on a bamboo bed. It was fun. When air conditioning came everything changed.

Reading with his ears

In the 1980s, after Deng Xiaoping’s economic reform policy, there was a new art movement and it was a boom time. My father was part of that.

As a child, I wasn’t so into sport and spent most of my time with my father, reading. It was a typical university professor’s family environment. My father opened his bookshelf to me, and I read a lot as a child – literature, history, art books and magazines.

Reading is one thing, but your ear can also read – I overheard conversations and gathered information. My father’s studio was in our home. Many people gathered there, and I always listened. It invoked my ambition to study art history, the same as my father.

Honour and privilege

When I was 18, I left Wuhan for the first time and went to Beijing to study at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA). It was a privileged education. At the time, the academy only accepted 40 to 50 applicants from all over China and only nine people in the Art History Department.

The academy was in the centre of Beijing, a 10-minute walk from Tiananmen Square, and all our professors were well known. The library was extensive, and I began to read a lot of magazines to practise my English.

Rock ’n’ roll

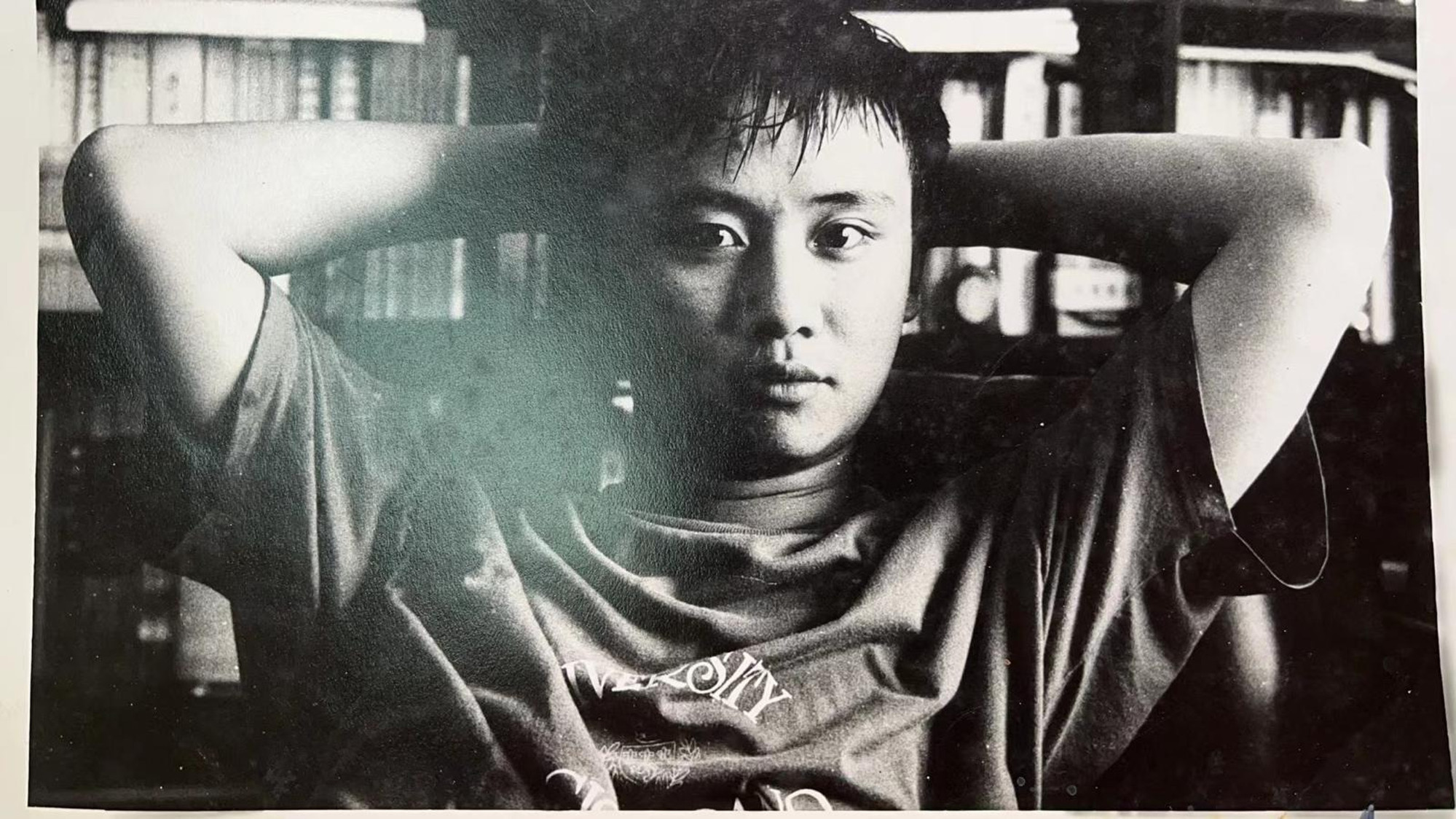

Art school was fun. There were no barriers between the students and the professors, some of them famous artists. There was no hierarchy, it was quite a democratic environment.

Art school is a nice place for subculture. Rock music was important with singers like Cui Jian and that generation of musicians. They practised in our school because it was in the centre of town and had the best studio. At that time, I must have appeared very rock ’n’ roll because I had long hair and wore jeans.

Master of destiny

After I completed the four-year degree, I applied to do a master’s but was not accepted. I was a good student, but at that time CAFA was not so open to modern art. It was seen as fashionable but not academic.

My professor liked me, so he gave me a small salary to work as a librarian in the school for a year. I applied for the master’s the following year and was turned down again.

I got a job working in a private gallery, Courtyard Gallery, one of the first commercial galleries in Beijing, which were all run by foreigners. The gallery was at the East Gate of the Forbidden City, a very exotic place, and I worked there for four years from 1997 as a gallery assistant.

In 1998, on my fourth attempt to join the master’s programme, I was accepted.

Bonnie Scotland

In 1999, I was selected by the British Council to be a visiting artist in Glasgow, in the UK, my first trip abroad. Also in my group was a dancer, Jin Xing, who is now a very famous transgender moderator on television.

I’d studied English for many years but when I got to Glasgow, I doubted myself – the Scottish accent is very strong. It was a nice three months at the Glasgow School of Art and the Centre for Contemporary Arts.

It got dark early, so I watched a lot of films, tried whisky and met lots of artists. Glasgow was poor and there were not many commercial galleries. Most institutions were non-profit and there were many alternative spaces.

Before Glasgow, I had no idea of the difference between the commercial gallery and the not-for-profit space. It was an eye-opener, and I thought, “OK, this is something we can try.”

Peak time

I met my wife, Yang, when we were seven. Our fathers were colleagues. She trained as a painter. We got married in 2001, had our first child in 2008 and our second in 2010.

In 2001, I completed my master’s. It was a year that changed China. It had recently been confirmed as host of the 2008 Olympics and then Shanghai was confirmed as host of the World Expo in 2010.

It was a peak time for China and the country was suddenly open. China was committed to cosmopolitanism and was open to contemporary art. The government didn’t want to show traditional China, they wanted to show contemporary culture.

Along with colleagues at CAFA, we formed the curatorial team for several major shows, including the 2003 Shanghai Biennale where I was the assistant curator.

Student bodies

Alongside the exhibitions, I was teaching at CAFA and doing my PhD – it was a busy time. In 1999, the government decided to enlarge the scale of higher education and the number of students admitted to college increased by more than 40 per cent from 1998.

By 2005, the number of new students was more than four times that of 1998.

Dreams come true

A friend, Wang Xiaoshuai, at the time an underground director, asked me to help him make a film. I’d always dreamed of making a film, so I helped with the promotion and fundraising, and became a producer for Shanghai Dreams (2005).

After many challenges, we managed to get a permit to show the film and it won the jury prize at the Cannes Film Festival. I was on the red carpet at Cannes.

The curators for the major museums in China and some in the United States, and the commercial auctioneers are all graduates of CAFA.

Joining the mafia

I was interested in not-for-profits so I built a not-for-profit space near the academy, which we called Universal Studios Beijing. Eventually we were sued by the real Universal, so we changed the name to Boers-Li Gallery.

When the financial crisis struck and we were struggling, we changed it to a commercial gallery. I stayed with that gallery alongside teaching for 11 years.

The curators for the major museums in China and some in the United States, and the commercial auctioneers are all graduates of CAFA. We are the mafia of the art world in China.

In China there is a law that you have to finish your PhD within 10 years, so in 2009, I took a one-year break to complete it. It was a nice time. My wife was pregnant with our second child and after working on my doctorate I’d take a walk with her in the afternoon.

Our daughter was born in June 2010 and I finished my PhD the same month.

Hong Kong bound

In 2012, I began to get bored with contemporary art projects in the government; it was quite bureaucratic. So I stepped down. I was offered a job as the senior curator at M+ in Hong Kong.

My wife wasn’t a big fan of Hong Kong and because we wanted our daughters to have Chinese as their mother tongue, she moved back to Beijing and they went to school there.

Our third daughter was born in Hong Kong in 2015 – which is how I could have three children, because at the time in China I could only have had two.

In 2020, when the older girls were in middle school, my wife moved back to Hong Kong, so they could be taught in English at the ISF Academy.

After 10 years here I’m a Hongkonger; it’s a global city and I truly believe people will come back. I’m excited for Art Basel and everything that is coming

World class

I was very privileged to work at M+; I believe it’s one of the great museum projects of the 21st century. In the next two or three decades there won’t be another big museum like M+. It is a world-class visual-culture museum, it is the museum that holds the most comprehensive collection of contemporary Chinese art.

M+ opened in 2021 and in 2022 I got the opportunity to join Tai Kwun as head of art. Unlike M+, Tai Kwun is small, it’s more like an arts centre and has no collection.

The main reason I joined Tai Kwun was that it’s small but beautiful, and close to the living art – you can react fast to the art scene. A great city like Hong Kong needs diversity – you should have an M+ but you also should have an energetic space like Tai Kwun.

Destination Hong Kong

After a decade of working for M+ I wanted to do something international, something for the young people, for the current art scene, to be more flexible. Now that the pandemic is over we can plan things.

I am excited to be involved in making Tai Kwun an important cultural destination not only for Hong Kong but for the region.

After 10 years here I’m a Hongkonger; it’s a global city and I truly believe people will come back. I’m excited for Art Basel and everything that is coming.