A way with words

Having fled to Germany in 2011, dissident writer Liao Yiwu continues to do what he does best - wield his mighty pen. He talks to Shirley Lau about how June 4 and the prison sentence that followed changed his world

Liao Yiwu walks in, expressionless. It is a sunny afternoon and warm in the cafe of Berlin's Academy of Arts. He makes eye contact from across the room but immediately breaks it and turns to his literary agent. When he finally steps forward, a minute later, he holds out his hand - a shy shake.

He has no intention of making chit-chat, the Chinese dissident says, but he is, apparently, in the mood to congratulate himself. Two minutes into our meeting, he points out that his new book sold 20,000 copies in Germany within two weeks of its release. In between sips of coffee, he says that he has a great deal of readers in Europe and that "I am quite famous and have considerable influence in the West".

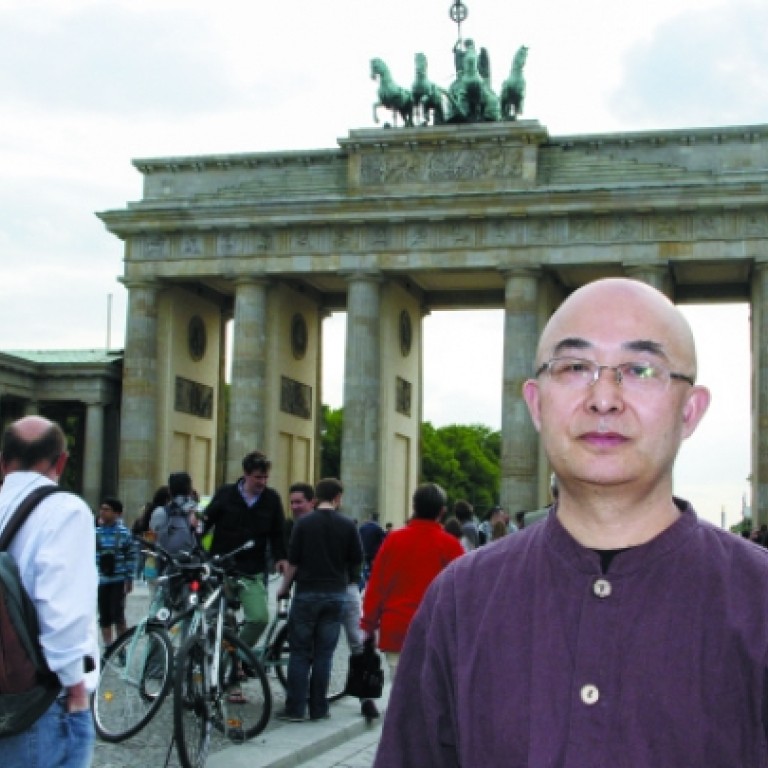

Perhaps he has good reason to sound a bit smug. A sizeable crowd is lining up near the academy's entrance for an observance marking the 80th anniversary of a Nazi book-burning event, wherein Adolf Hitler's followers tossed thousands of books filled with "un-German ideas" onto a bonfire in central Berlin. Liao is among an international cast of renowned speakers that has been invited to address the gathering.

Since he arrived in Berlin, in July 2011, after having slipped across the Chinese border into Vietnam, the Sichuan native has become known in the West as a brave writer, musician and dissident who persevered with his literary pursuits in his home country despite being under the watchful eye of the authorities and harassment by the police. He is best known for having penned the bestseller (2008), a colourful collection of stories about real people from the lowest rungs of Chinese society, and, most recently, for winning the German Book Trade Peace Prize for 2012.

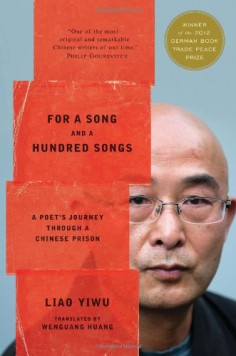

Readers in the West, he says, "see a high literary value in my work. They also see me as a window through which they understand China". Long-time journalist Philip Gourevitch has said Mark Twain, Nikolai Gogol and George Orwell would have recognised Liao "at once as a brother in spirit and in letters". In the foreword she pens for Liao's newly released prison memoir, , Nobel literature laureate Herta Muller compares Liao with author Boris Pasternak in terms of the political pressure both men endured before their works saw the light of day.

Liao started writing the book in his cell, on the backs of envelopes and scraps of paper that his family had passed furtively to him. In 1995, a year after he was released, the police raided his home and seized the manuscript. It took him three years to complete a second version, only to have that confiscated in 2001. Each time his work was taken, he "felt utterly hopeless but decided to start all over again".

In 2011, the third version was smuggled out of the mainland and published in Taiwan and Germany. The French edition, released to critical acclaim a few months ago, is emblazoned with the words "The book that Beijing wanted to burn" on the cover. The book is now being translated into Czech, Italian and Swedish, among other languages.

"When I wrote in China, I did not see much hope," says Liao, 54. "My books were sold at those temporary street stalls where goods were laid on the ground," he says, bursting into a laugh for the first time. "People could only read my books secretly.

"I never thought things would turn out this way. Not many writers can make a living solely out of writing. I am an exceptional case and I feel very lucky."

The success of his books in the West has financed the recent purchase of an apartment in Charlottenburg, an affluent neighbourhood in West Berlin.

"The entire process of building a home for myself in a new place felt really good," says Liao. "When I first came here, I only had a bed."

Liao writes in Chinese, the only language he knows. During his early days in Berlin, the government arranged for him to take German lessons from a private tutor but he stopped after three months, because he was too busy with work. Despite not speaking the lingo, he says, he has had no trouble integrating into life in the German capital.

"I chose to come to Germany instead of the US because American history doesn't have much in common with Chinese history. But German history does," he says, in Putonghua, with a faint Sichuan accent. "This country went through the Nazi period and East Germany was under communist rule. I feel an affinity with it."

Born in 1958, the year the Great Leap Forward began to sweep across the mainland, Liao suffered from oedema, which causes swelling of the tissues, as a child and nearly died.

His father, a high school Chinese-literature teacher, was branded a counter-revolutionary during the Cultural Revolution. To protect their children, his parents filed for divorce and the youngsters were left in the care of their mother. During that period, Liao would often skip school and - carrying fabricated travel documents - hitch rides across Sichuan by jumping onto moving trains.

After school, he worked as a cook, then as a truck driver on the Sichuan-Tibet Highway. It was then that he developed an interest in poetry, reading Baudelaire and Keats, among others, and writing poems for literary magazines, for which he won some national awards.

Then came the student pro-democracy movement in 1989, which altered Liao's world forever.

"June 4 completely changed the destiny of our generation. Before that, we still had some hope for our country," he says. "There are two periods in my life, one before prison and the other post-prison. Before going to prison, I was a snooty poet, free-spirited and freewheeling. I chased a dream filled with literature and the energy of youth. I read greedily. Then the June 4 crackdown happened and I went to prison, which was like a knife that cut deep into my flesh."

In the early days of the student movement, the letterbox of Liao's Sichuan home was stuffed with pamphlets about democracy and open letters and petitions seeking signatures, he says. Liao tossed them out "with contempt" and took pride in his own "cool-headedness", as he describes it in his memoir. But his nonchalance proved short-lived.

One night, he heard the crackle of fireworks outside and the communist anthem echoing in the air "like a requiem filled with tears and prayers". He raced to the rooftop of his building, where a crowd had already formed, and watched demonstrators marching in the streets.

On June 3, 1989, he composed a long poem called , predicting the killing of innocent students. After the crackdown the following day, he made an audiotape of himself reciting the poem and circulated it via underground channels in the mainland. A year later, when he and some friends made a film called as a sequel, to appease the souls of the dead, the police were alerted and arrested everyone involved. As ringleader, Liao was sentenced to four years in jail.

Humiliated by prison guards, tortured (sometimes with an electric baton) and deprived of his freedom, he twice tried to take his own life, the first time by hitting his head against a wall.

"Being handcuffed from behind you can't do anything on your own. You need help when you pee and poo. You can't even wipe yourself. There is no dignity. I was very scared of this kind of thing," he says, shaking his head. "On the spur of the moment, I tried to end my life."

Liao's hands were again cuffed behind his back when he made a second attempt to take his own life. He lost his temper while being interrogated and abused, jumped onto a table and tried to leap through a window he'd smashed with his foot. His interrogator saved him by holding onto his other foot.

In 1994, upon his release, Liao discovered his wife, who had been pregnant at the time of his arrest, had left him, taking their daughter with her. And his registration had been cancelled, rendering him unemployable. With a flute he had learned to play in prison, he began to work as a street musician and would take up odd jobs in teahouses and bookstores.

Liao kept in contact with other dissident writers, including Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, who is serving an 11-year sentence in Liaoning province for inciting subversion.

Liao has spent less than two months in total with his daughter, who is now in her 20s. That, he says, is "a pity", but he has no regrets about the "crime" that landed him in jail.

"I think many people under a communist dictatorship share this kind of fate. My father did; my teacher did. They all fought back. The only difference is they didn't write down their experience, and I do."

"[Writers] need to work hard to show the less informed the truth", he says. "Here in Germany, everyone from adults to children knows the history of Hitler and the Jews. It's a crime to glorify Hitler. But in China there is still a lot of misunderstanding about Mao Zedong. How was he different from Hitler and Stalin? There is misunderstanding because the intellectuals haven't worked hard enough to tell the truth to the younger generation."

In recording what he sees as the truth, Liao favours a somewhat micro-historical approach, focusing on people on the fringes of society rather than on major events. For , for example, he interviewed 27 people he had met in prison or after his release who he considered to be social outcasts or downtrodden. They include the manager of a public toilet, a leper, a professional mourner, a human trafficker and a grave robber.

"I don't know what is going to happen in China," he says, "but my strength is in writing. There are many people whose lives are not recorded. So I write them down."

His books - often written from memory - are brimming with fine detail. Is it possible, though, that some of his memories have been distorted by the passage of time or that he has tended towards exaggeration?

"What I do is literature, which is not the same as field research. You don't write like you are doing a research report," he says. "Surely I have forgotten a lot of things … but as I wrote the memoir the second and third times, there were new memories that emerged. That's how memory works, and the process of recollection has helped my writing a lot."

Liao insists he does not care about politics but he believes that if "a writer has no time for politics, that doesn't mean he has no conscience".

He is currently writing articles and getting involved in cultural events to press for the release of close friend Li Bifeng, a poet and businessman in Sichuan who was jailed for five years in 1990 for his involvement in the 1989 movement and was recently sentenced to 12 years for contract fraud, a charge Liao considers groundless.

When it comes to his homeland, Liao doesn't mince his words: "China is the biggest rubbish dump in the world," he says, repeating what he has said in previous interviews. "It is such a big country and it is wreaking havoc to the environment. North Korea may have its problems but it is a small state whose actions cannot affect the whole world, whereas pollution and many other things from China can. I don't see any future for the country unless it disintegrates into different regions. This is because the value system of the Chinese Communist Party is collapsing. Corrupt officials are fleeing the country. Nobody is capable of ruling it."

He reserves his kindest words, however, for his home province, where his octogenarian mother still lives.

"I think Sichuan is the most interesting place in the whole of China. Its food is delicious and it produces half of the country's baijiu [rice wine]. Sichuan people are good cooks, diligent, free-spirited and interesting. If we were to elect a head of state, we would certainly pick a chef or a wine connoisseur. I don't care about so-called Chinese identity. I just have faith in freedom.

"In my next life, I would want to be a Sichuan native again, and Sichuan would be an independent country. That would be wonderful!" he says, erupting into peals of laughter.