How Angkor Wat alternative Koh Ker, with its tiered temples and ‘magnificent’ artefacts, gives a window into the Khmer Empire without the crowds – for now

- For many visitors to Siem Reap, Cambodia, Angkor Wat is the go-to Khmer temple site, but two hours’ drive from the city is Unesco World Heritage listed Koh Ker

- The huge complex features tiered temples and statues said to be ‘more dynamic’ than at other Khmer sites. The best part is that word’s not out yet about Koh Ker

I’m looking at a seven-tiered pyramid that has more in common with Mexico’s Chichen Itza temple than it does the structures often associated with Cambodia’s Khmer kingdoms. What’s more, I’ve got the site to myself.

There are no selfie-stick-wielding tourists and no children hawking dusty guidebooks. But I can’t help thinking the days of peace and quiet are numbered, partly because Koh Ker, the Khmer temple site I’m exploring, was given Unesco World Heritage status in 2023.

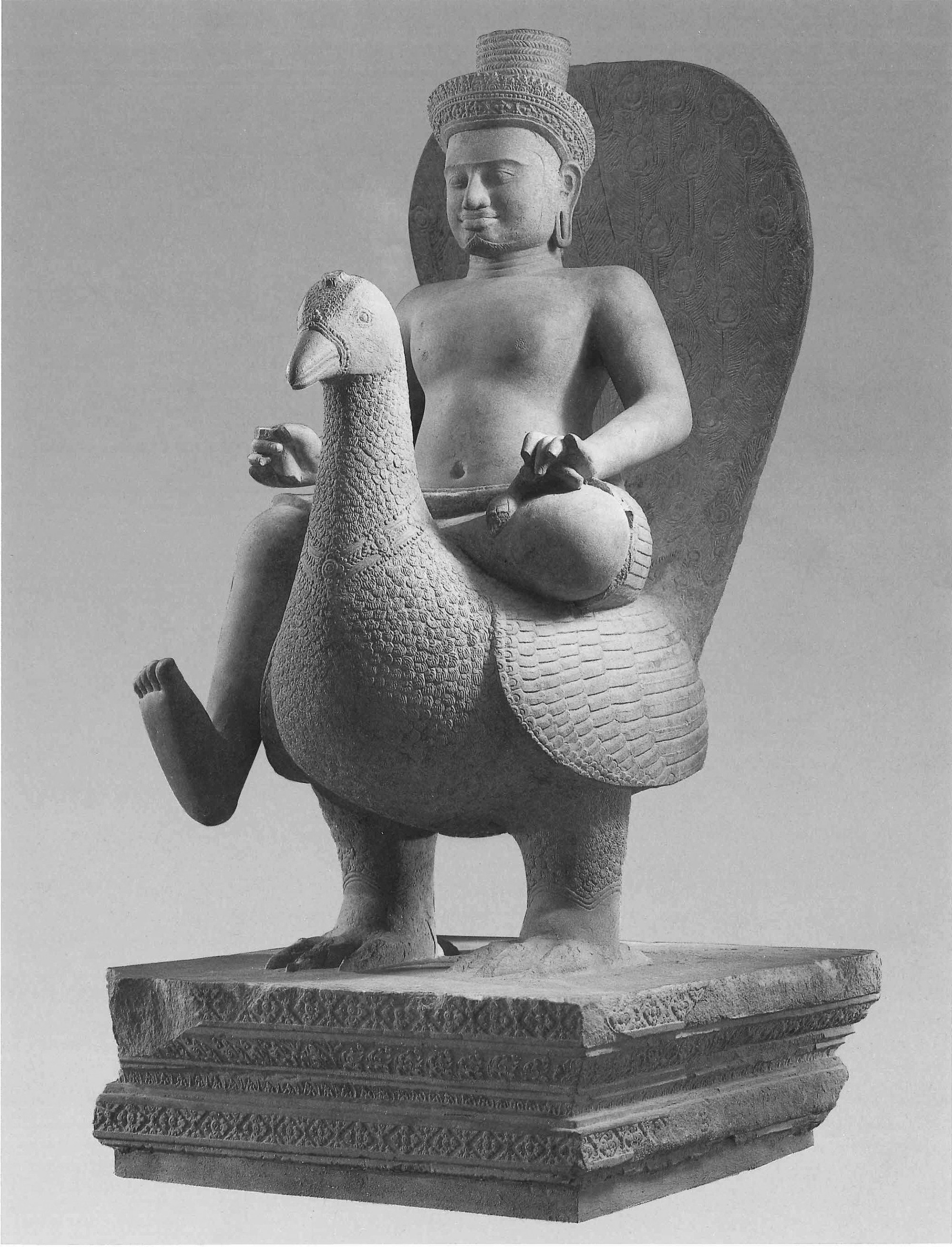

Although there are similarities in architectural style between the two, several of Koh Ker’s Brahmanic temples and prasats (sanctuaries) bear more detailed inscriptions and many of its statues depict characters rarely represented elsewhere, one being a Hindu god astride a peacock.

Comprising more than 100 distinct structures, some of which are mere ruins, Koh Ker is a two-hour drive from Siem Reap, and the sense of remoteness is palpable.

My guide – engaged in Siem Reap for US$130 – leads me to the summit of Koh Ker temple by clambering up a rickety staircase recently nailed to the crumbling stonework. At the top, I perch on stonework to soak up the view – jungle so dense that it’s hard to see nearby temples.

The five towers of Prasat Pram (pram means “five”), which is beside the site’s access road, are almost entirely covered in undergrowth. One tower appears to be more tree than temple, thanks to the gnarled trunk towering above it and the tendril-like roots cascading down the stonework, forming a tangled web that fans out across red soil before disappearing into the ground.

The loss is still evident: bricks tossed aside by looters are piled in the chambers of many of Koh Ker’s temples and shattered stone carvings lie in the dust.

A stone elephant once stood guard at each of the four corners of Prasat Khnar. Today, only one remains in place. Two are missing and the remains of another have been placed on the ground, the ornately carved body propped up by the amputated trunk and legs.

It’s widely accepted that most of the looting at Koh Ker can be blamed on an Englishman called Douglas Latchford.

A smooth-talking self-proclaimed arts expert, Latchford, who died in 2020, offered villagers huge sums for artefacts, and it’s suspected he paid Khmer Rouge child soldiers to bring him looted goods.

Latchford sold the booty on to private collectors and museums, including the Denver Art Museum in the United States, which returned several statues to Cambodia in 2023, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York.

Gordon was initially contracted by the United States Department of Justice (a large number of Latchford’s stolen artefacts ended up in America), although he now lives in the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, and works closely with the Cambodian government, which has awarded him citizenship in recognition of his work.

“Koh Ker was a favourite of Latchford because of the distinct style of the sculptures,” Gordon says. “The sculptures there are much more dynamic than those from earlier and later Angkorian periods.”

Avoid the tourist hordes at these non-Unesco heritage sites

He cites Prasat Krachap, a collection of five temples a 10-minute walk east of the main structure, as a brilliant example of what sets Koh Ker apart.

“It’s my favourite spot,” Gordon says. “Its true meaning and purpose is still a mystery, but it has the most inscriptions of any temple in Cambodia – there are thousands of names. For me, it serves as a testament to the genius builders of Koh Ker, but also to King Jayavarman IV and his son, King Harshavarman II.”

Among the stolen relics from this temple retrieved by the restitution team of Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts – with the help of people such as Gordon – are statues known as Skanda on the Peacock, and Skanda and Shiva, which are now on display at Siem Reap’s Angkor National Museum.

“These particular items are magnificent in their artistry, and I believe they tell the personal story of the kings of Koh Ker,” Gordon says. “We know from the looters they were found in a small chamber, and have found fragments of their pediments on site.”

Some of those who ravaged Koh Ker’s temples are now helping to retrieve its treasures while also passing on vital information about the location of ruins long since reclaimed by the jungle.

Gordon tells me that many of the villagers who live near Koh Ker were involved in the theft or are descendants of looters. Some now work as guards at the site, and there’s a sense that many are keen to right the wrongs of the past.

Angkor’s Ansel Adams – photos show ancient temples in new light

“I was first taken [to the Prasat Krachap] by the head of the looting gang, a man whose code name was Lion,” Gordon says. “With his directions, a team of archaeologists carried out excavations and found a number of pediment fragments and exquisite roof carvings buried underground. The team even found a fully intact carving of a lion.”

Gordon hopes that Koh Ker’s Unesco designation will result in more museums, galleries and collectors returning their stolen treasures.

After the two-hour drive back from Koh Ker, I grab a bite to eat on Pub Street, a neon-drenched avenue in downtown Siem Reap where backpackers gather to knock back cheap towers of Angkor beer.

I chat to a tourist who’s spent the day navigating Angkor Wat’s crowds, and he tells me he’s never heard of Koh Ker. I advise him to visit before word gets out.