In Anatolia, Turkey, there’s history at every turn, from a 3rd century Roman bridge to a castle ‘made with milk’, and some of the earliest evidence of bureaucracy

- Invaded by Greeks, Persians, Romans and other civilisations, Anatolia’s sights, including castles, caves, churches, mosques and tombs, bring history to life

- Most stunning are mountaintop decapitated statues honouring the leader of a forgotten kingdom, but there are less dramatic attractions, such as a coffee museum

Anatolia, the Asian portion of Turkey, has far more to offer than hot-air ballooning over the cave dwellings of Cappadocia, images of which are all over Instagram.

For thousands of years this region between Europe and the Middle East, most of it plateau over 500 metres (1,640ft) above sea level, was invaded from both east and west by wave after wave of Hittites, Phrygians, Cimmerians, Thracians, Greeks, Persians, Seleucids, Romans and others.

Many of them left their mark on both the landscape and the culture before the Seljuk Turks arrived from Central Asia in the 11th century and laid the foundations of the modern Turkish state.

As tourism returns to an area that was on the periphery of the February 2023 earthquake that struck eastern Turkey and northwest Syria, those whose travel decisions are driven by checklists will find the region satisfyingly sprinkled with Unesco World Heritage sites from multiple cultures, including caves and castles, tombs and tumuli, but without the crowds.

This is a landscape of crumpled beauty, and of schoolroom history lessons brought to life: the site of the earliest agriculture, the first settlements and, as befitting a region once part of the Byzantine Empire, evidence of the beginnings of bureaucracy.

From Elazig, a two-and-a-half hour flight east from Istanbul, it’s a short drive north to the ancient town of Harput, first settled 4,000 years ago, where a fortress once protected a crossroads of trade routes, including an old Silk Route coming west from Persia.

‘Most staggering disaster’ of 20th century now offers unique photo ops

The long-ruined castle dates mostly from the early part of the Ottoman Empire, which lasted from the 15th century to the early 20th century, and shoots up sheer-sided over the town, as if sprouting from the large limestone block on which it stands.

While calls to prayer from various mosques echo around the hillsides, there are views down from the castle’s battered battlements to the 3rd century Church of the Virgin Mary, still in use by resident Assyrians.

Amid a warren of streets in the town is the 12th century Ulu Mosque, one of the oldest still in use anywhere. Its photogenic patterned brick minaret leans seven degrees off the vertical, reminiscent of the leaning tower of Pisa.

Nearby Harput Museum, a well-restored 19th century house still furnished in the style of the time – ornately carved wooden furniture, oil lamps, traditional carpets, and with a child’s cradle hanging from the ceiling – feels less like an institution than a home from which the family has just stepped out.

Tradition has it that, because of a shortage of water, Harput Castle’s mortar was moistened with milk, giving it the alternative name of Milk Castle. But as the drive southwest to Malatya reveals, water is no longer a problem.

Damming for multiple hydroelectric projects in the 1970s submerged many a valley, and villages were relocated on the slopes above them.

Their low houses clustered around domes and minarets, they sit beneath snow-capped peaks and are prettily reflected in lakes dotted with buoys holding up trout farm nets. The calls of cockerels drift across the still waters.

Malatya is ringed by apricot orchards that fund the construction of rapidly developing suburbs, and the city is making deliberate efforts to attract more visitors, with excellent museums of archaeology, local culture, textiles, cameras (Asia’s largest collection) and, most appropriately, coffee.

The drink’s origins go back to when the Ottoman Empire included Yemen, the source of the coffee beans.

The town’s biggest draw is a 30-metre-high mille-feuille of archaeological treasures called Aslantepe, or Lion Hill, which dates back to 6000BC.

Each of at least seven successive civilisations built dwellings, temples and palaces of mud and straw there, which melted back into the landscape after each settlement was abandoned, overcome by invaders or destroyed by fire. The remains of each would provide the foundations for the next.

Uzbekistan: a journey to 3 ancient cities reveals why you should visit

Archaeological excavations continue, but have so far revealed layer upon layer of artefacts, instructively piled one on top of the other in date order. These include some of the earliest swords found anywhere in the world, and seals that pre-date the invention of writing, some of which can be seen in the town’s archaeological museum.

Both are evidence of an organised and hierarchical state, the earliest bureaucracy yet discovered, with an elite providing military protection and collecting food as taxation, sealing its stores with clay seals.

In 2001, archaeologists found a room containing seals that had been broken open stored in an orderly manner suggestive of an archive.

The excavated remains are substantial, with many surviving walls at head height, so it is possible to have the feeling of walking in the streets of thousands of years ago. Photographs at each entranceway display what was found in each location, and bring its purpose to life.

A two-hour drive south towards Adıyaman, on a winding route through steep-sided valleys with occasional terraces given over to tobacco, is a trip forward in time, but only to around 200AD and the construction of one of the oldest surviving bridges in the world: the Roman bridge at Cendere.

In Colditz country: the little visited castles of Saxony, eastern Germany

Built by the XVI Legion to honour emperor Septimius Severus (who reigned from 193–211) and his wife, Julia Domna, the elegant single arch of warm yellow stone, 120 metres long, crosses the Cendere river as it emerges from a narrow gorge.

Two Doric pillars at the south end carry inscriptions praising the imperial couple, and originally two pillars to the north glorified their sons, Caracalla and Getta, who reigned jointly after Severus’ death.

But after Caracalla killed Getta in order to take complete control, he had all evidence of his brother removed from monuments across the empire, and the bridge is now short one pillar.

Despite restoration, much of the original stonework remains intact, and the bridge was still in use until the recent completion of the much longer concrete span visible in the distance downstream. Benches for picnicking and admiring the view down the valley have been installed.

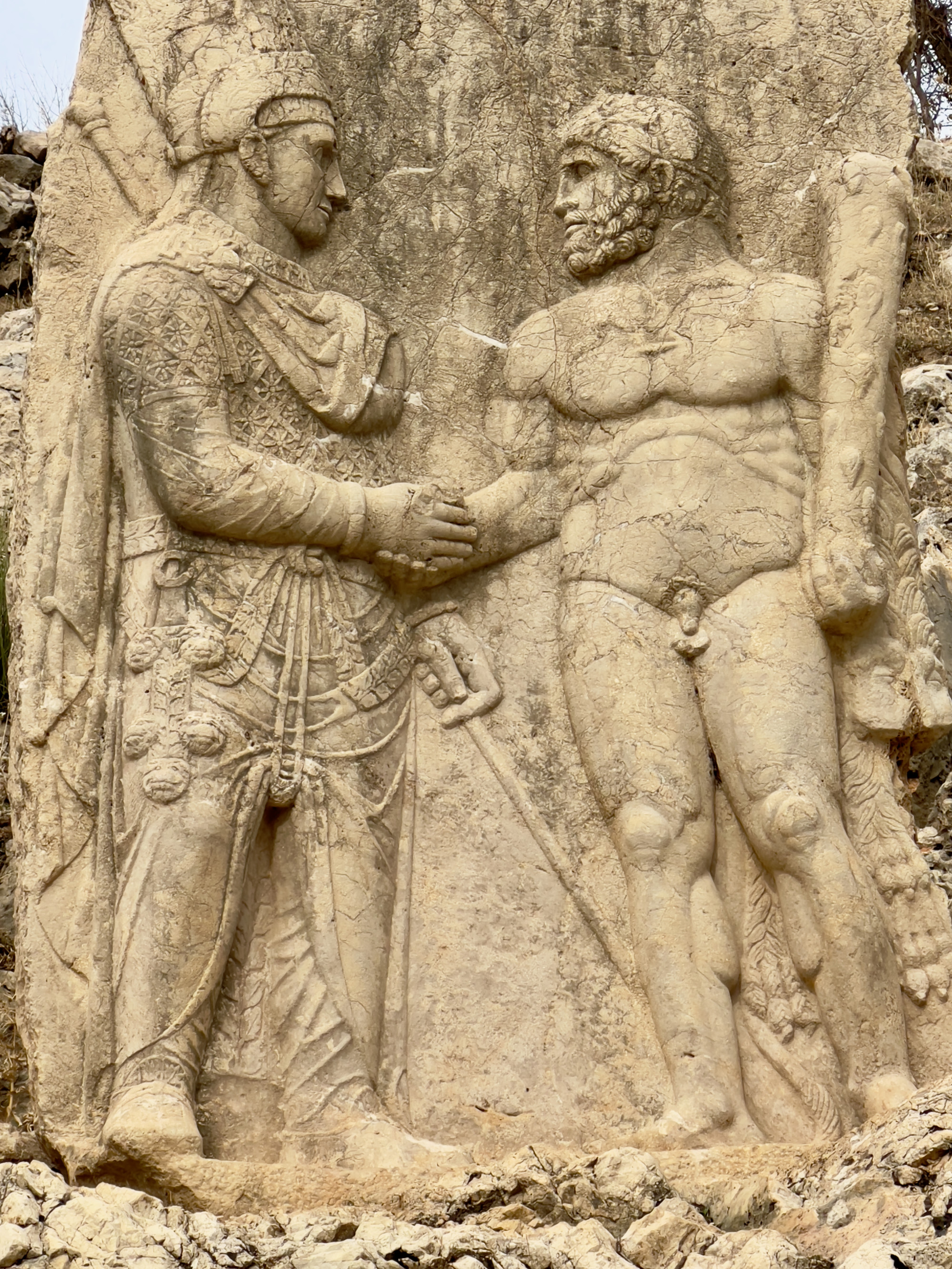

A short drive east is the royal burial complex at Arsameia, where a winding uphill track leads past giant stone reliefs of dexiosis – scenes of handshakes between kings Antiochus I, or Mithridates, of the 163BC – 72AD Greco-Persian Commagene kingdom, and Greek gods such as Apollo and Heracles. These carvings were propaganda that placed the human kings on the same level as the immortals.

The hillside is perforated with tunnels to underground burial sites, one of which is marked by a long and astonishingly well preserved inscription in Greek by Antiochus I (who reigned from 70-31BC) describing the construction of the site and the rituals to be performed there.

Perhaps the region’s most spectacular monument, from the same Commagene period, is Mount Nemrut, 30 minutes further along a road of magnificent curves that climbs up the 2,150 metre peak.

Here terraces line two sides of a vast summit tumulus of small stones beneath which Antiochus is buried, each terrace with giant decapitated figures of the king and assorted gods.

In some cases, the torsos have all but vanished but the giant stone heads remain in eerie rows as if fresh from some public execution, their faces still full of expression.

Greek and Persian gods such as Heracles, Apollo, Mithras and Zeus, chosen for their recognition by peoples to both the east and the west at the time, stand figures of Antiochus himself, and of protective lion and eagle statues.

Visitors are essential to the slowly reviving local economy, so now is a good time to bring out the smartphone and follow historical precedent by making sure you’ve been seen in the company of gods.