Tokyo from the water: a river cruise in Japan’s capital reveals glimpses of nature, and history, amid the concrete and steel

- Greenery is scarce in Tokyo, yet the natural world penetrates the urban one via a network of waterways largely buried and forgotten beneath a tangle of traffic

- Their banks are verdant, and herons and ducks fly overhead; history is ever-present in bridges, their names and the scars of wartime destruction they bear

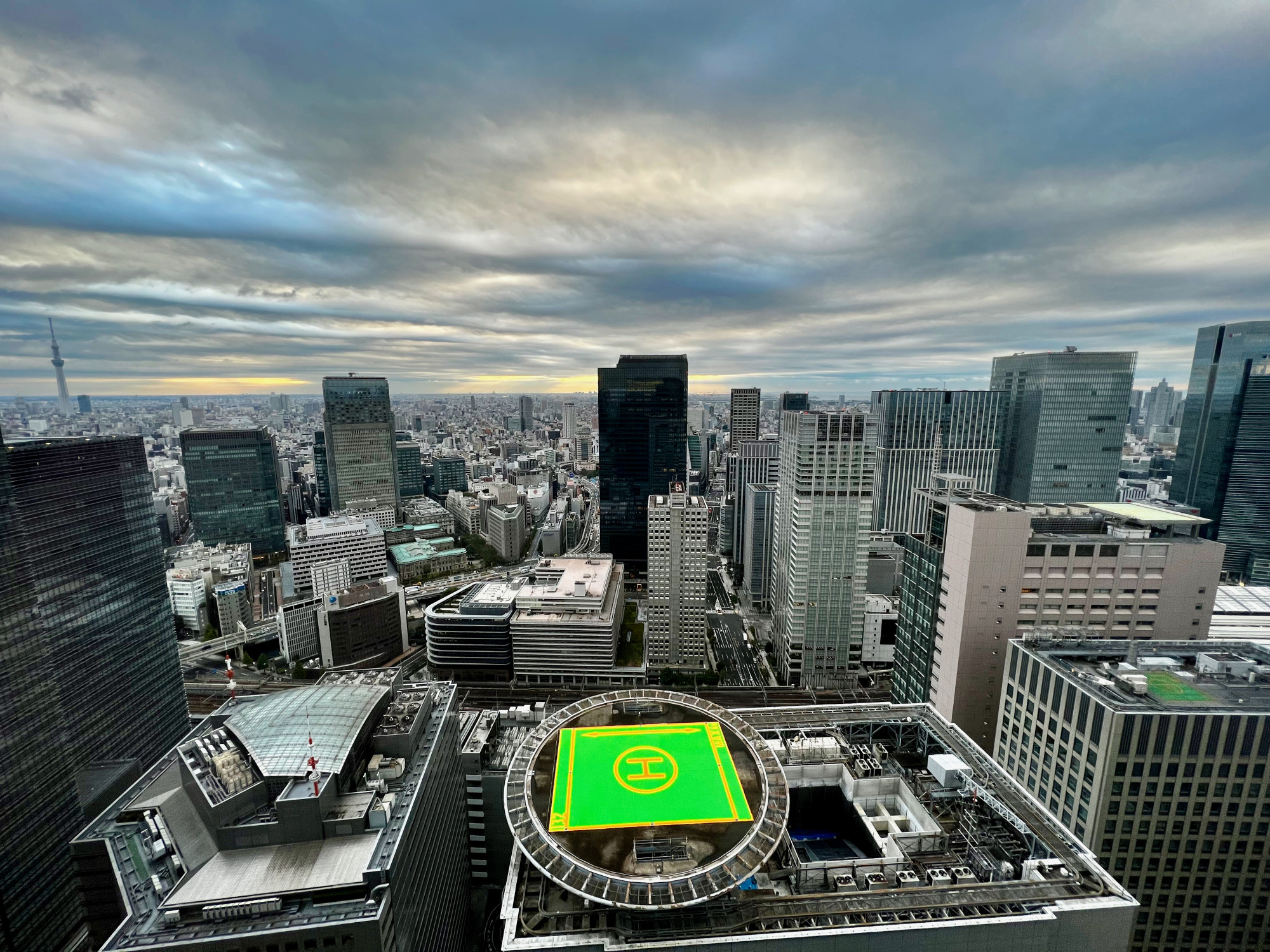

Tokyo is a jumble of areas of low-rise sprawl laced tightly together by highways and railways, all pulsing with the movements of millions of commuters.

Visitors, drawn to the sights in Yoyogi Park and Ueno Park, and to the leafy grounds of the Imperial Palace, tend not to notice that the proportion of green space to total space in the city is very low – just 7.5 per cent, in fact.

Residents cultivate handkerchief-sized gardens and window boxes, or turn railway embankments into flower beds. Tiny backstreet shrines are screened by topiary, and this hankering for horticulture extends even to the city’s tower-topping luxury hotels.

At The Café at the Aman Tokyo, it is possible to dine on dainty pastries while shrouded in the five-star hotel’s own “forest”: 3,600 square metres (39,000 sq ft) of tangled woodland transported from outside the city to the heart of the Ōtemachi financial district and left free to grow its own way.

The Park Hyatt hotel has a bamboo grove beneath a glass pyramid high above the city, and the Mandarin Oriental’s wallpaper, carpets and furnishings are luxuriously woven with nature-related motifs.

The hotel is presented as a giant tree, with root-related decor in the entrance lobby and leaves and branches on its 38th floor check-in level.

But roots reach down towards water, and it’s through the metropolis’ waterways, largely buried and forgotten beneath a tangle of traffic, that the natural world truly penetrates the urban one.

At the historic Nihonbashi (literally “Japan Bridge”), which was built in 1911, cast iron mythical creatures atop the low arches look down on a wooden boat tied up below on the Nihonbashi River.

This is the Riverboat Mizuha, which seats around a dozen people on deck or in the cabin, and takes passengers on 90-minute bilingual tours (in Japanese and English) through Tokyo via loops around four of its rivers.

Three of these are canalised in whole or in part, and all rise and fall by up to 2 metres (6.5 feet) with the tides in Tokyo Bay.

The current bridge is the 20th on the same site, but it is dwarfed by the twin routes of the Metropolitan Expressway which run above it, supported by large pillars embedded in the river.

Japanese duty-free goods vending machines make shopping easy for tourists

A viaduct over a bridge over a river gives a taste of what’s to come on the tour, with up to three layers of railways and roadways stacked overhead, scissoring upwards as if competing to reach the light. The boat slaloms between pillars as if trying to avoid being stepped on by a giant.

Some bridges are plain and practical, but others are more adventurous – the concrete Nishikibashi bridge has art deco detailing in its green grilles, for instance. But viewing the bridges from beneath is less about their architecture than about patterns and textures, and the sense of space – the guide’s voice echoes.

Tokyo’s Kitchen Town covers all your Japanese food preparation needs

The Tokiwabashi, a bridge originally built in 1877, is thought to be among the oldest in Tokyo and was damaged by the offshore earthquake that caused the Tohoku tsunami in 2011.

It was completely dismantled and reassembled, and the whiteness of the 30 per cent of new stone added at that time against the grey and black of the old gives it an attractive speckled look.

There is history at every turn. The name of the Ichitotsubashi reveals that it was once just a single timber, and the Kijibashi’s name gives away its past proximity to cages for pheasants, which in centuries past were offered at feasts to Chinese and Korean ambassadors.

At one point, the lichened boulders of the 400-year-old walls of Edo Castle line a channel to the left.

The boat is quiet, and little of the traffic roar spills down to the river, which is also a haven for wildlife: tall blue herons, smaller white ones with yellow hoods, the odd duck and plenty of dragonflies. Ivies tumble down stone walls and some steep banks are a tangle of greenery.

This may be the heart of the city, but it feels like a backwater.

There are few other vessels, but a flock of jet-bikes – motorbike-style personal watercraft – weaving from side to side under one bridge suddenly gives the scene a Mad Max air. But they slow; the riders, garishly outfitted in neoprene, pause to give us a wave, as do walkers on bridges overhead.

We make a sharp right turn into the Kanda River and pass beneath an old brick railway bridge; a hole in its steel floor and pitting in its brickwork caused by shrapnel are rare surviving evidence of the city’s destruction in World War II.

We may have emerged from under the expressway, but now a canyon of six-storey buildings envelops us, and leads us to a section where the canal was carved through higher ground.

The high-arched Hijiribashi, (literally “Holy Bridge”), was built in 1927, and connects a Confucian study hall on one bank to a Russian Orthodox church on the other. The depth of the waterway forces Tokyo Metro’s Marunouchi Line to cross in sunlight before disappearing underground again.

There’s another right turn on to the Sumida, a genuine river broad enough to induce fleeting agoraphobia after the confined spaces of the canals. Wakes from the passing of larger vessels occasionally rock the boat.

In the Edo period (1603–1867) there were only five bridges crossing this river, and the modern ones are grander cable-stay or suspension bridges high enough to make the wide crossing without obstructing shipping. The French-designed Chuo-Ohashi cable-stay bridge is said to resemble a samurai warrior’s helmet.

We reach Tokyo’s “little Manhattan”, an area of shipyards and heavy industry, before passing a flood gate into the narrow Kamajima River to the right. This is a 350-year-old canal where sailing ships from all around Japan’s coast were unloaded in days gone by.

A left turn back on to the Nihonbashi takes us under the extraordinary tangle of an aerial junction between two highways, just before we regain the pier.

Cruises in Tokyo Bay offer more views from sea level. Symphony Cruise employs small cruise liners that are effectively floating restaurants.

The cruises afford views of the man-made island of Odaiba, home to some of Tokyo’s more unusual modern architecture, and to the 150-year-old low stone bulwarks of the defensive islands that failed to stave off foreign warships and the consequent end of the shogunate in the 19th century.

These are all enjoyed while taking a small but well-executed afternoon tea.

The least natural part of Greater Tokyo can also be reached by water on a nighttime cruise with Keihin Ferry along the industrial coastline at Yokohama, which resembles the future Los Angeles of the movie Blade Runner.

The commentary is only in Japanese, and seeing foreigners on board isn’t common. The boat is a battered little ferry that looks as if it spends its days transporting dock workers.

Here in the dark are great spiky towers topped with leaping flames, giant columns of unknown purpose, red-and-white striped chimneys, and dinosaur-like derricks all studded with flashing red lights to warn off aircraft, their reflections shimmering in the waters.

Silvery buildings throb, hum and flicker in the flashing lights, and writhe with gangways, spiral staircases and ducting.

The boat is dwarfed by colossal tankers being unloaded beneath floodlights. We’re sneaking in the back way where other access is forbidden, and it’s all faintly menacing, but as we return to Yokohama past a gaily illuminated funfair, the passengers break into applause.

All in all, it’s the views from the water that give you a complete picture of the city.