After 150 years of rail travel it’s still at the heart of Japanese culture – and worth the trip to Japan to see

- A high-speed bullet train network and a web of scenic but lightly used rural lines criss-cross Japan, 150 years after service began between Tokyo and Yokohama

- To see some of that history – celebrated in woodblock prints and hotel rooms with train simulators – head to Saitama’s railway museum, or simply take a ride

There seems no better way to mark the 150th anniversary of the opening of the first railway line in Japan – a narrow-gauge route from the Shimbashi district of Tokyo to the port at Yokohama – than to arrive in the Japanese capital by “bullet train”, or shinkansen super express, and stay at Tokyo Station.

There are trains everywhere you look in the city, and Tokyo Station, the hub of a vast rail network, is a train spotter’s paradise.

It’s impossible to overstate the comfort and convenience of Japan’s famous high-speed rail system, which offers departures every few minutes from city centre to city centre at near-airline speeds, and laces the country together.

There are winding routes with scarcely a single conventional kilometre, all bridge and tunnel, that connect stations on the bullet train network to tiny coastal and interior communities.

Opened in 1914 during previously cloistered Japan’s generation-long love affair with all things Western, Tokyo Station – inspired by the Netherlands’ Amsterdam Centraal – was built as a temple to travel to match the great European terminuses.

No sooner does the door of the sleek bullet train slide open than a smartly liveried woman from the Tokyo Station Hotel – waiting in exactly the right spot – insists on wheeling away my suitcase, apparently determined to make my trek through the terminus’ labyrinth as smooth and effortless as the journey from Hiroshima, on the other side of the country, has been so far.

Tokyo Station is the capital’s busiest in terms of departures, being the terminus of multiple suburban routes as well as long-distance bullet train lines. Several of the city’s subways pass through it, as does the elevated Yamanote Line, which provides a scenic circular tour of the city.

All of this adds to the convenience of staying at the station.

Within its recently restored exterior, there’s now a vast underground network of passages with restaurants and shops as well as track entrances.

I happily follow the porter, with her jaunty pillbox hat, up escalators, along corridors, around corners, down passageways and out through an octagonal domed space featuring the entrance to an art gallery that houses a railway-related exhibition.

We turn along the building’s 300-metre-long red-brick frontage, pass the porticoed entrance that is reserved for the emperor and finally turn back inside, entering a calm space with elegant ladies taking afternoon tea, and from which the rumble of the railways is excluded. By long tradition, clocks here are set five minutes fast to avoid a last-minute sprint for the platform.

Today, travelling by bullet train is part of the pleasure of visiting Japan and not merely a means to an end. But in 1872, Japan’s rail system got off to a much more modest start, with the opening of a line built on Cape gauge (3ft 6in). This was narrower than standard gauge (4ft 8½in) but cheaper to construct, and much of Japan’s conventional network still uses it.

The hissing black tank engines that pulled the trains were built in Britain and shipped out, along with the engineers and administrators needed to construct and run the line. They were also required to educate their Japanese successors.

Hardly high speed, trains took 53 minutes to complete the 29km (18-mile) route from Tokyo to Yokohama, although trips on any of several modern lines still take about 40 minutes.

Locomotive No. 1, the first to enter servicce, spends its retirement at the Railway Museum in Saitama, a city that can be reached in about 45 minutes from Tokyo on the Keihin-Tōhoku line. This line was originally opened in 1914, the same year as Tokyo Station.

To reach the museum – operated by JR East, one of Japan’s major rail companies – a transfer from the Keihin-Tōhoku line to the New Shuttle line is required, with the latter hinting at the immense variety of rail systems in Japan today.

Running on an elevated track, its rubber-tyred trains are capable of the extraordinarily tight turns necessary to snake between various high-rises before arriving at the spacious, modern complex.

Kyoto-Nara-Osaka luxury train in Japan offers a window on history

Locomotive No. 1 has pride of place at the main entrance, a brass plate on its side declaring it to have been manufactured at the Vulcan Foundry Co, in the Lancashire town of Newton-le-Willows, in 1871.

A neighbouring engine dating from 1880 has a diamond-shaped funnel that gives away its American origins.

Funnels were so shaped to stop sparks from scattering and starting fires when the engine was passing through the American prairies, although neither that nor the cowcatcher on the front seem particularly relevant to an early line in damp Hokkaido, northern Japan, for which it was imported.

Bullet trains have become increasingly streamlined since the original Series Zero, which first went into service in 1964 and has a face like an airliner. Subsequent models’ noses have grown Pinocchio-style to the shoe, then shoehorn, shape of the latest express.

At the museum, several majestic bullet train examples sit alongside quotidian commuter trains of every period.

Visitors can board many of them and appreciate their period upholstery while taking in mannequins that depict the attendants of the era who would have dispensed bento boxed lunches.

There are also various opportunities to climb into simulations of train cabs with touchscreens and buttons to push at every turn.

In some cases steam engines have been cut away to reveal their inner mechanisms: the firebox, the sandbox and the regulator valve, along with once-clanking connectors, pistons and cylinders.

There are simulators for everything from steam engines to shinkansen super express – an experience that doesn’t even require a visit to the museum.

As part of the anniversary celebrations, JR East’s Metropolitan hotels in Tokyo’s Maranouchi and Ikebukero districts are offering simulators in some of their rooms. And these are the same machines used to train drivers.

Many of Japan’s rural lines depend on cross-subsidy from the profitable bullet train network and crowded urban commuter lines to survive. This business model is, however, becoming less sustainable as Japan’s population shrinks, despite a new emphasis on sustainable travel and plans to further extend the bullet train network.

On many rural railway services, the passengers appear limited to train enthusiasts and gaggles of Burberry-scarfed girls on their way to school, who stare at their phones rather than at the scenery outside.

Despite this, trains remain a prominent feature of Japanese culture both in literature and the visual arts.

Celebrations of the anniversary include an exhibition at the Tokyo Station Gallery, Art and Railway – 150th Anniversary of Railway in Japan (running until January 9), which points out that 1872 was also the year bijutsu (“fine art”) first entered the vocabulary as a replacement for shoga (“painting and calligraphy”).

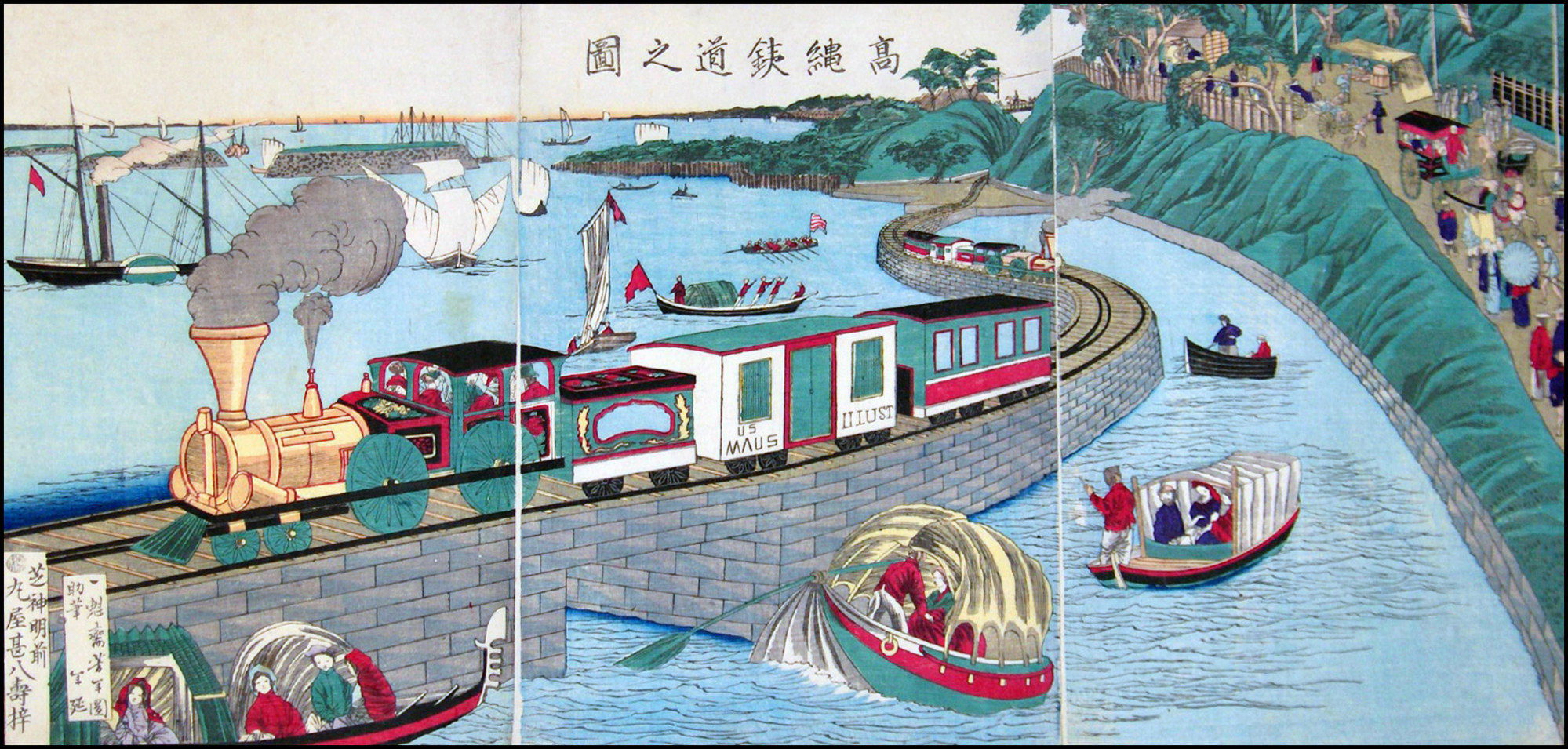

As part of the exhibition, ukiyo-e woodblock prints – familiar overseas for their images of beauty spots along ancient Japanese highways like the Tōkaidō – depict late-19th century opening ceremonies for new railway lines.

In one image, flag-bedecked foreign warships float behind a newly completed line to the city of Kobe, and another, from a 1920s series of “Famous Places of Tokyo”, shows the full red-brick frontage of Tokyo Station with an airship and biplane overhead. One from 1889 reproduces the view from a scenic railway in Iwate prefecture, in northern Japan.

It seems Japan was not only an early adopter of trains, but also of train simulators.