Chinese Thai politician’s legacy to his hometown a reminder of how minority influenced Thailand’s economy, politics and society

Banharn Silpa-archa, a Thai prime minister, built a museum shaped like a mythical Chinese dragon to celebrate China’s culture and Chinese migrants’ part in Thailand’s story. A new statue will soon honour the champion of his hometown

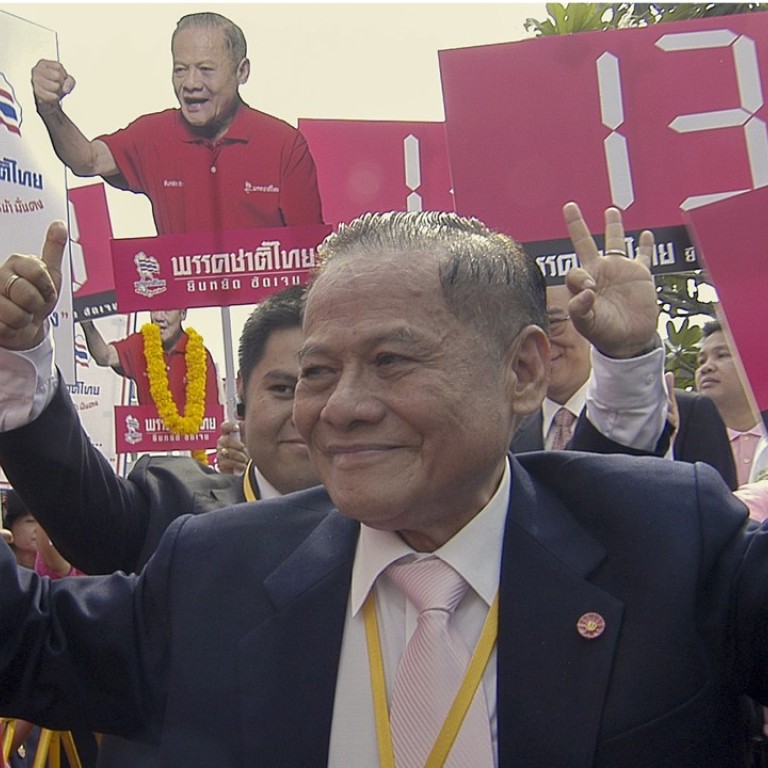

On August 10, the residents of Suphan Buri will receive yet another reminder of the man who put their town back on Thailand’s political map – Banharn Silpa-archa, a prime minister in the mid-1990s and provincial politician extraordinaire.

A towering statue of Banharn, a diminutive man in real life, will be erected at the entrance to the Dragon Descendants Museum built in the shape of a dragon, part of Banharn’s bountiful legacy to the town 100km (60 miles) north of Bangkok.

With subway’s arrival, Bangkok’s Chinatown faces gentrification

That a giant dragon 35 metres (115 ft) tall and 135 metres long – a mythical creature of ancient China, not Thailand – sits in the centre of Suphan Buri is testimony to the historical openness of Thailand to its citizens of Chinese descent and to the tremendous influence these “dragon descendants” had on its society, economy and politics. Banharn, who died two years ago at the age of 83, came to personify the successful provincial Thai politician during his 40-year public career.

Born in Suphan Buri – the town gave its name to the surrounding province – the young Banharn helped at his father’s tailor’s shop in the market. His father was of Chinese Chiuchow descent, from Guangdong province in southern China, while his mother was ethnic Thai. Neither was rich. According to family lore, Banharn quit school at the age of 16 and moved to Bangkok to make his fortune. Before he left he visited the town shrine, where he vowed to beautify the sanctuary and develop his hometown should his prayers for wealth be answered.

Such shrines are found in many Thai towns, but the one in Suphan Buri is unique for its distinctly Chinese characteristics, and pillars depicting the Hindu gods Shiva and Vishnu. The origin of the pillar gods remains a mystery, but it is known that the Suphan Buri’s Chinese community built the shrine and began worshipping there about 170 years ago, according to Dragon Descendants Museum director Chanchai Tippanet.

“The Chinese community back then was already big in Suphan, mostly Chiuchow and Hailam [Hainan] Chinese,” Chanchai says. “They would arrive at Samut Sakhon [a coastal province south of Bangkok] and take a boat up the Tha Chin River to Suphan Buri, then look around for work and a place to live.”

Suphan Buri is in Thailand’s well-irrigated central plains region that has been the country’s traditional rice basket since the founding of Ayutthaya as the kingdom’s new capital in 1351. Scholars of Thai history say Suphan Buri predated Ayutthaya as a major religious centre and power base.

“It was one of the major towns at the foundation of Ayutthaya, and the family which came to dominate Ayutthaya for its first couple of hundred years was the Suphan Buri ruling family,” says Chris Baker, co-author with his wife, Thai academic Pasuk Phongpaichit, of numerous books on Thailand.

Unfortunately, the town fell victim to ceaseless wars over the ensuing centuries. By the 16th century, as a result of devastating wars between Burma and Siam, Suphan Buri became a wasteland.

Jacques De Coutre, a Flemish merchant who passed through Suphan Buri in 1594, described it as a ruin, populated only by war elephants and their mahouts, and overrun with “tigers, of which there were so many in the area that we were not safe from them even sleeping in our perahaus [boats]”.

Much of western and central Thailand was abandoned after the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, when it was sacked by the Burmese, and thereafter during more than five decades of wars under the leadership of Thai King Taksin, the warrior monarch who ruled from 1767 to1782 and who restored the kingdom of Siam.

Taksin drove back the Burmese and conquered other foes while establishing his new capital in Thonburi, across the Chao Phraya River from Bangkok.

The king, himself of Chinese descent, mustered the Chiuchow Chinese community to be his shipbuilders and mercenaries in the wars against the Burmese, bequeathing them the title of “Jin Luang”, or “Royal Chinese” because of the services they rendered.

Bangkok temple where dogs are given human funeral ceremonies

Chiuchow evolved as the most widely spoken Chinese dialect in Thailand partly because of the sea trade between southern China and the Gulf of Thailand (propelled by the monsoon winds and by the economic and political turmoil gripping southern China at that time).

Chiuchow immigration to Siam escalated in 1727, when Qing dynasty rulers dropped draconian regulations against migration amid crop failures and famine in southern China. They flocked to Bangkok, which became the capital of the new Chakri dynasty in 1782, and to other coastal cities, eventually moving inland to underpopulated Siam.

“Suphan Buri started to be repopulated around 1820, and from that time I think you had a lot of Chinese coming in,” Baker says. Banharn’s ancestors made Suphan Buri their home, but for the young, ambitious Banharn, the provincial town did not offer enough opportunities.

“So he packed a bag and got into a boat – back then there was no road to Suphan – and it took him a week to get to Bangkok,” says Varawut Silpa-archa, Banharn’s son. But not before going to the town shrine to make his famous oath.

“His legacy, his life, was all based on that oath,” Varawut says.

In Bangkok the young Banharn got into the construction business and focused on government contracts, where he made his fortune. In 1976, on the advice of Booneua Prasertsuwan, a former speaker of the House of Representatives and member of the Chart Thai (Thai Nation) Party, Banharn entered politics as a representative of Suphan Buri. He would continue to win every election in the province for the remainder of his political career, thanks primarily to his post-election benevolence.

Chef who started with street cart on making Bangkok Michelin guide

Before 1976, he had already spent some of his private fortune building schools and hospitals in the province.

“Prasertsuwan talked to my father and said, if you really want to do something for your hometown, it doesn’t matter how much money you have privately, it won’t be enough. The only way to do it is to use the government’s money, and to do that you have to become an MP,” Varawut says.

Banharn held numerous cabinet posts, culminating with that of prime minister from July 1995 until November 1996. His premiership was cut short by numerous corruption scandals that forced his resignation. He nevertheless made sure he kept his constituents happy in Suphan Buri, sometimes jokingly called “Banharn Buri”.

Prasertsuwan talked to my father and said, if you really want to do something for your hometown … The only way to do it is to use the government’s money, and to do that you have to become an MP

Using government funds he built Highway 340 linking Bangkok to Suphan Buri, one of the best two-lane highways at the time. His political opponents accused him of wasting the budget and catering to his constituency.

“I can’t blame them because the initial road ended in a fence, and then turned left into Suphan Buri, and beyond the fence was nothing, just rice paddies,” Varawut says. “But that was just the first phase.”

Eventually Highway 340 was extended to Nakorn Sawan, in central Thailand, offering an alternative to Highway No 1, the main road to the north.

Besides roads, irrigation canals, schools and utilities – which require public budgets – Banharn spent his personal fortune creating tourist attractions in his hometown, such as a clock tower (like a small Big Ben) and the 123.25-metre-tall Banharn-Jamsai Tower (a miniature Tokyo Skytree). Jamsai is the name of his widow.

“It was like he was playing a SimCity video game, but it wasn’t a game, it was an actual city and he actually did it,” Varawut says.

Then there was the Dragon Descendants Museum. The concept of building a museum was hatched in 1996, when Banharn was still prime minister, as a means of commemorating the 20th anniversary of Sino-Thai diplomatic relations that year.

The plan was under study for 10 years and the museum took another 600 days to build, finally opening on December 24, 2008. It cost 380 million baht, paid for largely by Banharn with donations from several wealthy Sino-Thai businessmen.

An accompanying “Celestial Dragon Village”, in imitation of Lijiang – a Unesco World Heritage Site in China’s Yunnan province – opened three years later, with souvenir shops and restaurants. All was built on a 30 rai (11.86 acre) plot of land around the town shrine that Banharn acquired over the years and donated to the Dragon Descendants Museum charity.

The museum was designed to instruct Thais about China’s culture and history. The 20-room museum – in the belly of the dragon – takes a visitor from the “Chinese origin myths” to the arrival of Chinese immigrants in Thailand. Earphones offering English and Chinese translations are provided.

Varawut, who now leads a reformed Chart Thai Pattana Party, also supervises the museum – and runs the province’s soccer club.

“My priority now is to make sure the party survives,” he says.

You’ll die for a coffee at this Bangkok ‘death cafe’

Varawut has a big legacy to live up to in Suphan Buri, where his father’s contributions loom large, as will, soon, his statue.

“The ethnicity issue is long gone in Thailand,” Varawut says. “Now it is just about politicians and the military, really.”