Coping with miscarriage: how one woman dealt with three losses and why she shares her experiences with others

- After her third miscarriage, Julie Sajnani-Nandwani began talking about her experiences to cope, sharing her story online and with friends

- According to one doctor, even in a woman’s best reproductive years, one in 10 pregnancies end in miscarriage between the sixth and 20th weeks of pregnancy

Between 2010 and 2013, Julie Sajnani-Nandwani suffered three miscarriages. “Natural miscarriages break you in a way you can’t explain,” says the 39-year-old mother-of-two. The last time, she says, it happened when she was in the bathroom at her son’s school.

“The worst part was: I had to bring myself to flush it and move on,” says Sajnani-Nandwani. Her husband was away at the time, so she had to pull herself together and take their son home and act as though nothing was wrong.

Although her husband knew of her struggles with miscarriages, she often suffered in silence. She would tell no one else about them, not even her mother or sister, as she didn’t think they would understand.

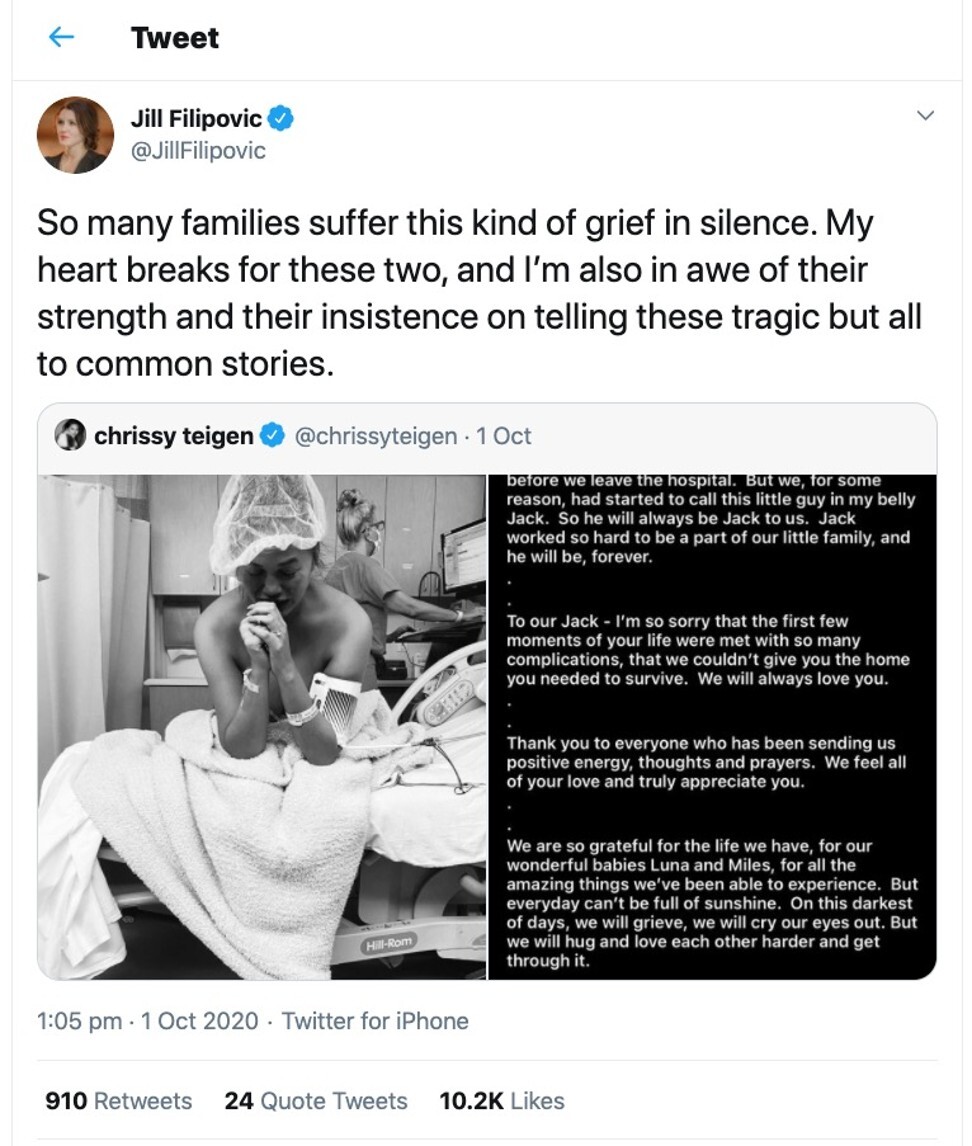

Teigen wrote: “We are shocked and in the kind of deep pain you only hear about, the kind of pain we’ve never felt before. We were never able to stop the bleeding and give our baby the fluids he needed, despite bags and bags of blood transfusions. It just wasn’t enough.”

She added: “We are so grateful for the life we have, for our wonderful babies Luna and Miles, for all the amazing things we’ve been able to experience. But every day can’t be full of sunshine. On this darkest of days, we will grieve, we will cry our eyes out. But we will hug and love each other harder and get through it.”

The Hong Kong couples not allowed to bury their children

Her husband Legend wrote: “This is for Chrissy. I love and cherish you and our family so much. We’ve experienced the highest highs and lowest lows together. Watching you carry our children has been so moving and humbling.”

The posts sparked various conversations online, from those who thought it was wrong of them to mourn such a private loss so publicly, to others who shared their own stories and defended the couple’s right not to suffer in silence.

Ten to 20 per cent of pregnancies end in miscarriage, according to the Mayo Clinic of Rochester, in the US state of Minnesota. The classification of miscarriage varies from place to place – in Hong Kong, a miscarriage is defined as the death of an embryo before 24 weeks of pregnancy.

“There’s always grief associated with such loss and the severity of that grief is context-dependent. Like everything to do with childbirth, it elicits strong emotions,” says Lord.

There should be … acknowledgement that there’s no right way to experience, grieve or lose your baby

According to Lord, even in a woman’s best reproductive years, one in 10 pregnancies end in miscarriage between six to 20 weeks of pregnancy. “As you approach 35 years of age, it goes up to about one in seven pregnancies, and by the time you get to age 40, it’s close to 50 per cent,” says Lord.

“That made me realise that nobody talks about it unless you talk about it,” says Sajnani-Nandwani.

From that moment, Sajnani-Nandwani began sharing her story, inviting others to share their experiences and asking if they have advice to offer. Women have since done so, including a friend who connected her to a yoga teacher to help her cope better mentally.

Sajnani-Nandwani had her own Teigen moment online in 2018, when she opened up about her miscarriages on a mum-focused forum. That post led to an outpouring of supportive comments.

“Somehow, you felt comfort knowing you’re not alone,” she says.

Frustrated Hong Kong couple finally get go-ahead to bury their miscarried son

Though opening up about such losses has helped, Sajnani-Nandwani admits she hasn’t fully recovered. She’s kept sonograms of those failed pregnancies but, to this day, she can’t bring herself to look at them. “I am still grieving in my own way, it’s still bottled up somewhere inside,” she says.

According to Lord, a woman’s beliefs about when the point of maternal responsibility begins, their cultural background, personal experiences, as well as their own coping mechanisms, all shape their experience after such loss.

“There’s a huge amount of potential dispute on a woman’s version of her beliefs around her loss versus another’s,” says Lord.

That partly explains the controversy surrounding Teigen’s posts. Supporters say no one should have to suffer in silence, while detractors suggest other women may have suffered just as much but have coped in a different way, says Lord.

“There should be … acknowledgement that there’s no right way to experience, grieve or lose your baby,” says Lord. She urged people to show greater understanding and tolerance towards women who go through pregnancy loss, and know that every woman’s response is different and unique.

At Lord’s practice, she says explaining to her patients why such loss occurs helps them to cope. More women choose to have children later in life, and maternal age is the strongest known risk factor for miscarriage.

Up to the age of 30, about eight per cent of pregnancies end in miscarriage; from 30 to 34 years, that rises to 12 per cent; from 35 to 37 years, 16 per cent; from 38 to 39, 22 per cent; from 40 to 41, 33 per cent; from 42 to 43, 45 per cent; and from 44 upwards, to 60 per cent.

Studies suggest that genetic factors may account for half of all miscarriages.

After an operation for a miscarriage to remove remnants of the pregnancy, the placenta is checked for genetic abnormalities. “Around 90 per cent of those pregnancies … show an abnormal number of genetic abnormalities,” Lord says.

“That relieves the guilt so much because it’s absolute proof women couldn’t have done better in caring for the baby as, from the moment of conception, that baby could not have survived.”

She emphasises that, other than by taking pharmaceutical drugs that trigger an abortion (and such medications have clear warning labels on this), “for most women, there is no way you can cause yourself to lose a baby”.