Gen Z trends last ‘maximum 4 weeks’, unlike punk and hippy culture of old: it’s why, on TikTok, things like cottagecore and girl dinner blow up and over so quickly

- Tomato girl. Cottagecore. Latte make-up. Girl dinner. Gen Z trends for looks and lifestyles have never been hotter – or blown over as quickly as they appear

- Experts say young people use them to bind themselves to a community, to build confidence, and foster creativity in a fast-paced world facing crisis after crisis

When it comes to fashion and beauty trends, we have entered an age of hyper-categorisation.

Summer 2023 saw periwinkle manicures renamed blueberry milk nails, and brown lips and sandy eyeshadow dubbed latte make-up.

These are just the tip of the iceberg, and two of the many trends to be labelled by social media users on TikTok and sites like Aesthetics Wiki in recent months.

But is this categorisation craze just for fun, or is there more behind Gen Z’s obsession with turning everything into an aesthetic fronted by a viral buzzword?

Thanks to fast fashion, social media and online shopping, trend cycles move quicker than ever.

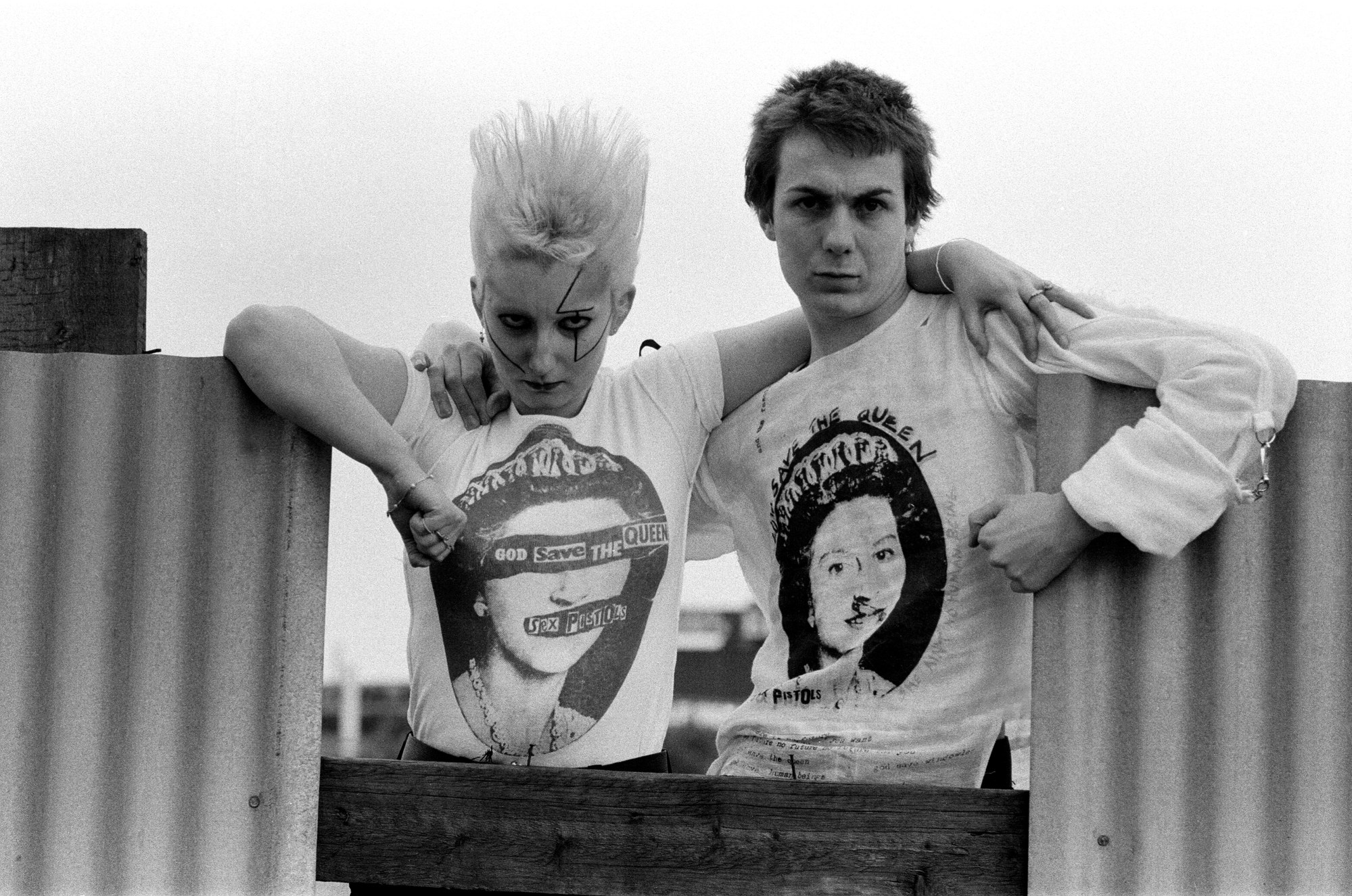

“Cut to the 20th century, where trends are pretty much a decade long … then cut to today, and what’s happening on TikTok and social media, where trends last [a] maximum four weeks before the next one comes along.”

There is a sense, when it comes to fashion and make-up, that everything has already been done before. There are only so many new ways to design clothes or apply make-up, and even colour charts have their limits. But ultimately, true originality is not quite the point.

Los Angeles-based psychologist Dr Jeanette Raymond explains how “most young people want to differentiate from their parents’ generation. One way of doing that is to rename what is already out there as something different so that they can identify with it, and use it as a badge to bind them to their peer group.”

What may seem frivolous is Gen Z’s way of creating a sense of belonging and tribe building in an increasingly digitised world.

Jessica Tang, trend and culture analyst at forecasting firm WGSN, tells the Post: “Young consumers today see aesthetic trends as an aspirational lifestyle that offers community and comfort, and turn to aesthetic plurality on social media to discover their identity, build confidence and foster creativity.”

While aesthetics may have replaced some aspects of traditional youth subcultures, can they ever really replicate their authenticity or organic social interaction?

This is the major difference between aesthetics and subculture. As Tang points out: “Gen Z don’t feel tied to any one aesthetic, and bounce between them freely, mixing, matching and creating new variations along the way.”

For some, this is the main appeal of aesthetics: you may dress like a tomato girl but be allergic, and you can tag yourself as cottagecore all while living in a city apartment.

As Guy Debord predicted in his seminal work of philosophy and Marxist critical theory, The Society of the Spectacle, back in 1967: “All that once was directly lived has become mere representation, the decline of being into having, and having into merely appearing.”

There has been some pushback from TikTok users against overzealous trend labelling.

Writer Syd Robinson refers to the rebranding of dark brown hair colours to “smoky espresso” and mousy blonde to “apricot blonde” as the “magazine-ification” of perfectly acceptable terminology. In a now viral post, TikTok user Katie Raymond called blueberry milk nails “dumb”.

It does not end with fashion and beauty. Too lazy to cook? Crackers and cheese at night is actually a “girl dinner”, with the hashtag racking up over 1.4 billion views.

While this all seems harmless enough, as YouTuber Mina Lee touches upon in her video about aesthetics, it can lead to forms of self-surveillance where even the messiest and laziest parts of peoples’ lives become a performance.

And while these moments may not be as aesthetically pleasing as a cottagecore get-up, there is nothing carefree and effortless about having to constantly think about capturing every moment on camera.

WGSN’s Alison Ho explains that “cute nicknames seem to help consumers sprinkle a bit of imagination into boring aspects of daily life”. And this is not just happening in the West; she raises the culture of nicknaming products and brands in Asia, which can be a way for shoppers to express their opinions and feelings about certain products.

It is not all escapism and fantasy. Unlike previous generations, the open nature of social media platforms like TikTok also allows for greater diversity in fashion and beauty, including but not limited to body positivity.

Antonino takes an optimistic view, saying: “Social media offers an unprecedented platform for challenging traditional beauty standards and promoting a more inclusive definition of beauty.”

And Eldridge, as a make-up artist, encourages users to have fun with trends. “It’s still really interesting, as long as you take it with a pinch of salt. It’s all a combination of marketing and fun.”