Chinese fashion brands with European character are bucking the local identity trend – and finding a market in millennials and Gen Z

- Patriotism might be in vogue for many Chinese fashion labels, but European-inspired brands like Juvil and Sans Titre are finding a willing audience at home

- The styles appeal to millennials and Gen Z with links abroad through travel and study, and those who view wearing such styles as reflecting their own success

Recent years have given birth to countless Chinese brands and designers that overtly and proudly embrace their Chinese identity. Some incorporate cultural motifs into their work, while others appeal directly to patriotic sentiment in their marketing campaigns.

However, a number of Chinese brands are bucking that trend and wearing European inspirations unambiguously on their sleeves.

Guangzhou-based Juvil is one such brand. Founded by Hong Kong entrepreneur Adrian Cheng of K11 and New World Development, the jewellery brand describes itself as “Scandinavian-inspired” and references “Nordic nature” and “Nordic flair” in its marketing materials.

In fact, on the brand’s website, it identifies itself in the persona of a white Scandinavian woman named Juvil, featuring a video showing her as “the happiest woman on earth”, strolling dreamily through a variety of pastoral scenes. The camera lingers on Juvil’s jewellery, using grass, trees and water as backdrops and evoking a comfortable life grounded in nature.

A European-inspired brand like Juvil might seem anomalous in the current fashion environment. A 2018 survey by financial services company Credit Suisse showed that Chinese consumers, especially those aged between 18 and 29 years old, were increasingly willing to choose domestic brands over international labels.

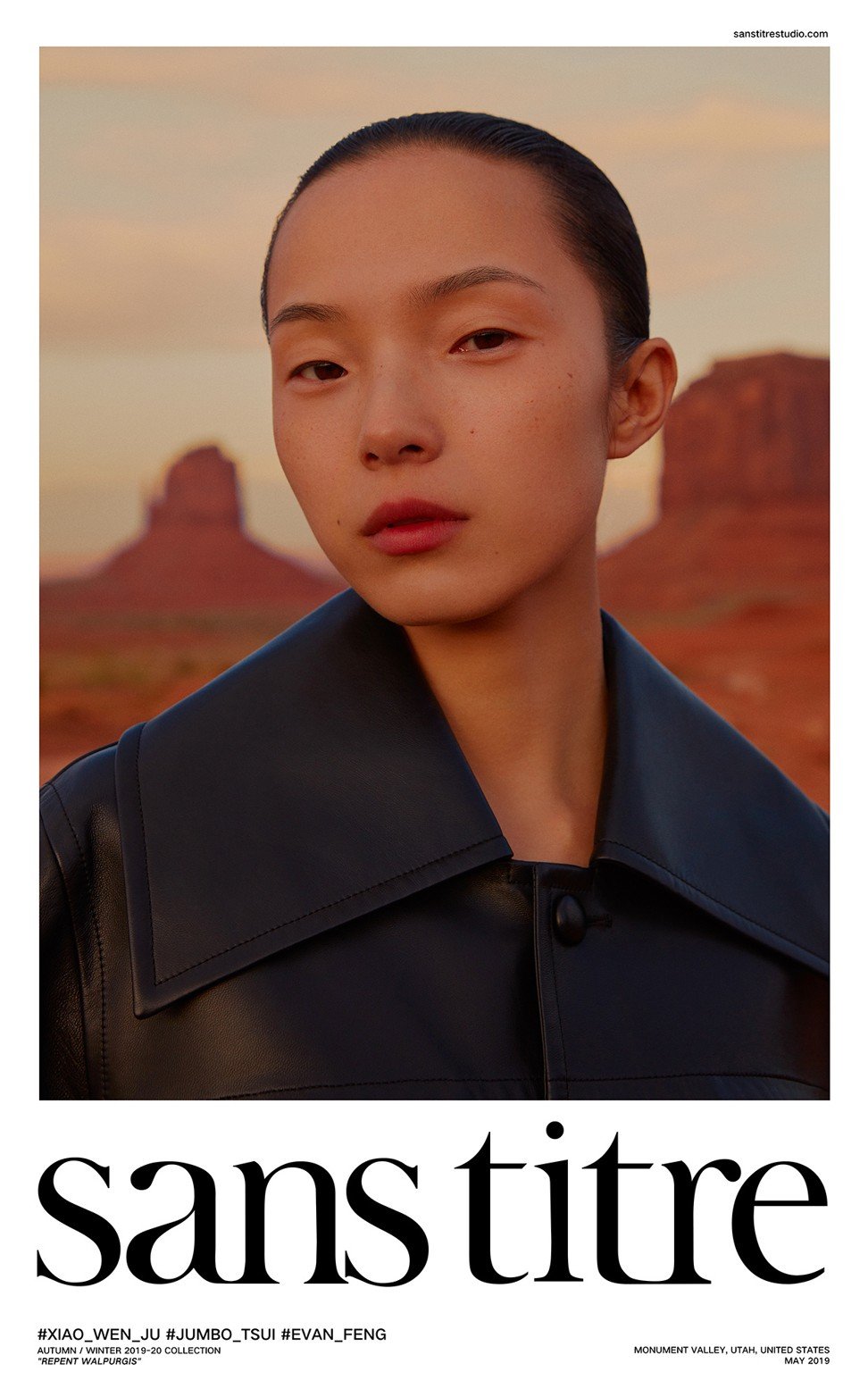

Fashion brand Sans Titre was founded in 2015 by designer Xu Jiazheng and photographer Jumbo Tsui. It is based in Beijing but, as the name suggests, the brand is heavily inspired by French style.

“Our experience living in Paris working in the fashion industry led to our obsession with the French language of fashion,” Tsui said. The pair have also incorporated Japanese elements into their designs, a result of time spent in Tokyo.

For Chinese consumers, a brand like Sans Titre affirms China’s success, perhaps even their own personal attainment. To these millennials and Gen Zs, a European aesthetic may not even seem “foreign”, but rather a style they have a personal connection to, whether through overseas travel or study.

This is, in many ways, the Sans Titre story. Xu studied at the prestigious Parisian fashion school Esmod, later working for Hermès, while Tsui lived in the French capital for four years, shooting for a number of luxury brands. Their work reflects their lived experiences and is representative of a generation of young Chinese people whose education and cultural fluency is a point of pride.

“With the fast growth of social media, the wall between ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ has already fallen down,” Tsui said. “We believe that our customers are not looking for a label or a sign on their clothes, but something that belongs to themselves.”

Juvil speaks to a similar sense of aspiration among consumers, appealing to a modern Chinese sophistication that takes in overseas travel, cultural literacy and appreciation for the natural world.

“While the founder enjoys visiting different places around the world, Scandinavia always holds a special place in his heart because of the spectacular aurora displays and the wealth of natural heritage and remarkable architecture,” a representative for the brand told the Post.

Juvil’s identity is unlikely to have happened on a whim. Cheng set up his company’s research arm, the K11 Future Taskforce, primarily to track the evolving Chinese millennial and Gen Z market. Cheng also launched venture capital firm C Ventures in 2017, to identify and incubate brands that could appeal to young Chinese consumers.

Juvil currently has branches in Cheng’s K11 mall in Guangzhou and in the new flagship K11 Musea development in Hong Kong. With Cheng’s expansive portfolio of brands and commercial developments covering fashion, jewellery, media and art, Juvil has room to grow, and the international aesthetic may allow it and similar brands to scale more easily to overseas markets.

British-Chinese designer Pauline Cheung, founder of Shanghai-based bridalwear studio Peony Rice, warned that brands with one foot in China and one in overseas markets face a tricky balancing act.

An “international” aesthetic may be appealing to Chinese consumers, Cheung said, “but it depends who you're targeting. Some things can go too far Western and the Chinese market doesn't really understand it.”

The interplay between a brand’s “Chinese” or “international” credentials has always shaped Chinese consumer perceptions. Just two decades ago, brands like Metersbonwe and Ochirly made a name for themselves by putting out approximations of contemporary European and American styles. Even 10 years ago, “international” and “Western” were taken as bywords for quality, and European luxury brands like Louis Vuitton were desirable status symbols.

However, Cheung believes there’s still a tendency to view foreign products as of higher quality than Chinese products.

“I do think people still look outside, not necessarily to the West, but just outside China,” Cheung said. “It's almost like confirmation that the product is better than the product that they get domestically.”

Cheung said that the key shift is the tilt away from Western-centric consumer preferences towards Japan, South Korea, Southeast Asia and beyond.

“I think a lot of this has to do with also where the Chinese can travel,” Cheung said, citing increasing interest in South American and Moroccan goods. “They opened Morocco up to the Chinese without a visa I think a couple of years ago, and all the travel agencies started promoting Morocco.”

The international sphere is important in other ways that still persist. When Cheung moved to China in 2006 for a job for a luxury brand – three years before she launched Peony Rice – making it internationally was a rite of passage for a Chinese brand.

“Back in the day, to be successful in China, it was almost like you had to get your brand overseas,” Cheung said. “To do shows, get some press, then bring it back to China, and then you will be successful. That still kind of flies.”

Tsui is doubtful that Sans Titre’s international association has given the brand a boost. “It helps, but it’s not that helpful so far,” he said. In any case, Tsui and Xu are not trying to position themselves or chase a preconceived target consumer.

“We don’t think it’s necessary to adapt what’s on trend in a certain region,” Tsui said. “We’re trying to show our ideas on Chinese spirit to customers, and we hope that it’s the customers who find us instead of us finding them.”