How Disney got kicked out of China over Martin Scorsese’s Kundun, a 1997 movie that ripped a hole in US-China relations

- About the early life of the Dalai Lama, Kundun caused tempers in China to boil over and was accused of being an interference in the country’s internal affairs

- Stuck between a rock and a hard place over its release, Disney took the coward’s way out – not that this did the movie giant much good

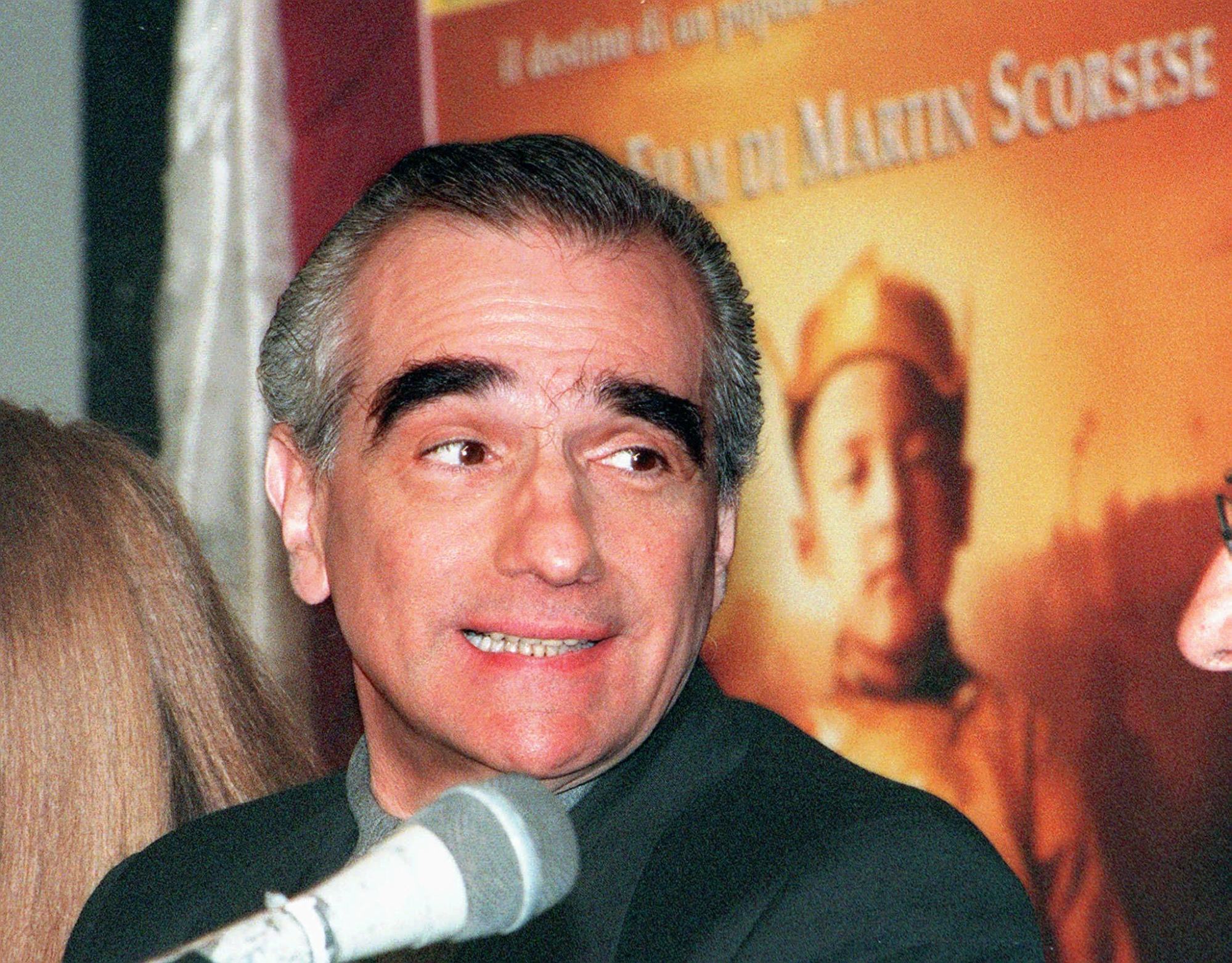

Director Martin Scorsese is no stranger to controversy.

Yet it was Kundun (1997), a contemplative drama about the early life of the Dalai Lama – played by Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong, a relative of the actual Dalai Lama – that caused the biggest furore, ripping a hole in US-China relations that took years to repair.

The first hint of trouble came in 1996, when Disney received a call from the Chinese embassy. It said the Chinese government was unhappy about Kundun (the Tibetan name for the Dalai Lama), which had started filming two days earlier in Morocco. The unspoken subtext? “Stop it.”

Although Universal had already passed on Kundun for fear of damaging its other business interests, the film hardly seemed worthy of an international incident. Despite wonderful production design, music and cinematography, it felt like the kind of mid-level prestige picture that nets a few Oscar nominations and then gradually becomes relegated to a career footnote for all concerned.

How 2012 shark movie Bait 3D became a monster hit at the Chinese box office

The problem in this case was that the system was China.

“We are resolutely opposed to the making of this movie,” said a Chinese film bureau official. “It is intended to glorify the Dalai Lama, so it is an interference in China’s internal affairs.”

Worse was soon to follow: on November 1, 1997, China’s Ministry of Radio, Film and Television sent a memo to the Motion Picture Association of America blacklisting Disney, Columbia TriStar (regarding Seven Years in Tibet) and MGM/United Artists (regarding Red Corner) for making films that “viciously attack China”.

It went on: “In order to protect Chinese national overall interests, it has been decided that all business cooperation with these three companies to be ceased temporarily without exception.”

Disney was, to put it lightly, in quite a fix.

If it released the movie, it would forfeit access to one of the world’s largest audiences, as well as a long-planned Disneyland outpost in Shanghai – all amounting to untold billions of dollars. If it didn’t, it would forever be known as the studio that sold out Scorsese, one of cinema’s greatest talents, to Chinese hypocrisy.

Instead, it took the coward’s way out, releasing the movie with as little fanfare as possible – on Christmas Day, no less – then shrugging when it made only US$6 million. Not that this did much good.

“All of our business in China stopped overnight,” Disney CEO Michael Eisner told The New York Times. Scorsese and the other filmmakers were banned from entering the country.

The next few years were characterised by some furious backtracking. Disney hired former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to smooth relations, and Eisner flew to Beijing to apologise to Prime Minister Zhu Rongji in person.

“The bad news is that the film was made,” Eisner said. “The good news is that nobody watched it.” It was an astonishing admission from the CEO of a major studio, and a hint of the power that China would start to wield in Hollywood in the coming years.

As for Kundun, the film received four Oscar nominations before becoming a footnote in Scorsese’s career.

“I personally think that, unfortunately, they [Disney] didn’t push the picture,” Scorsese admitted to the BBC in 1998.

But was that really because of China? “Who knows? The market China represents is enormous, not just for Disney, but many other corporations around the world.”

And that’s the difference between real life and Hollywood movies in a nutshell. In real life, it’s the system – not the little guy – who wins.