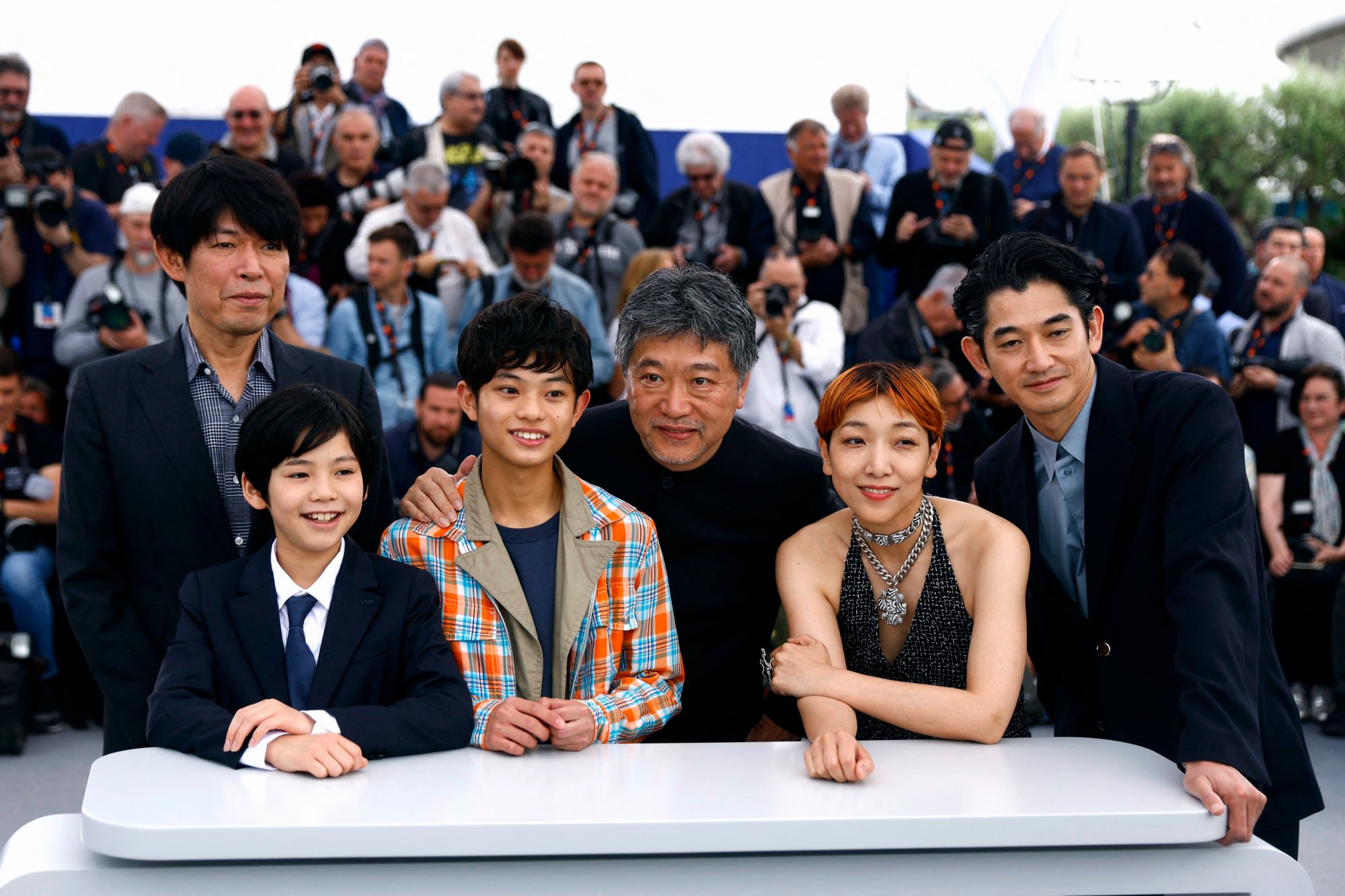

Hirokazu Koreeda on why Monster, best screenplay winner at Cannes, isn’t just another Japanese movie to draw from Rashomon

- Monster examines from various perspectives the intense friendship between two schoolboys and what it reveals about bullying, peer pressure and love

- The director says he sees the story as both a celebration ‘of these boys and what they found’ and a statement about Japanese society’s twisted view of the world

“Of course, that’s a film that I respect greatly,” he tells the Post, admitting that this three-part story owed a debt to Kurosawa. “I understood that straight away, but I wanted this not to be just about an interesting structure.”

In that time, Koreeda has become regarded as Japan’s premier auteur, if not quite on the level of Kurosawa, his delicate stories of human interactions, especially the family dynamic, finding favour with art house cinema audiences around the world.

This twisted view of the world that adults might have gets reflected upon the children. That’s what happens in Japanese society

While Rashomon deals with the murder of a Samurai, seen through various conflicting and subjective viewpoints, Monster’s world is more domestic.

It begins with Saori (Shoplifters’ Sakura Ando), who discovers that her young son Minato (Soya Kurokawa) has seemingly been injured by a teacher, Mr Hori (Eita Nagayama), in connection with a disciplinary matter.

She rages at the school principal, but there’s more than one side to the story, as becomes clear when events are replayed through the eyes of first Hori and then Minato.

Minato’s feelings for his classmate Yori (Hinata Hiiragi) form the emotional epicentre of Monster. The physically weak Yori is bullied by his peers, a cruelty that Koreeda blames more on the adults in their orbit.

“The teacher tells the boys to be like men, and these adult values are compressed into children’s society,” the director says. “So this twisted view of the world that adults might have gets reflected upon the children.

“That’s what happens in Japanese society, and that’s where the cracks start to appear. School is just representative of that.”

I’ve had experiences myself of having feelings for someone that I shouldn’t have feelings for.

In the simplest of ways, Koreeda shows how school life is about the survival of the fittest.

Minato “gives in” to peer pressure when others pile rubbish onto Yori’s desk. But when these bullies suggest Yori make fun of a girl, he won’t.

“Yori refuses to be a machine,” says Koreeda, praising the boy’s courage.

The close attachment between Yori and Minato, who is confused by his feelings, puts Monster in the same bracket as Lukas Dhont’s 2022 Oscar nominee Close, which also dealt with the intense friendship of two boys.

“I think the fact that this boy [Minato] begins to see a monster in himself is because he has emotions that he doesn’t understand and he can’t give voice to,” says Koreeda.

“And that emotion is that he loves someone … which is a normal emotion. But he can’t say that, and it just so happens that someone that he loves is another boy. But that is something that can happen to everybody.

“I’ve had experiences myself of having feelings for someone that I shouldn’t have feelings for. And I think if someone had just told these boys that ‘That’s OK’, that would have released them.”

Arriving in Pride month, the film’s exploration of LGBTQ themes may be subtle, but it will surely be embraced by the gay community. Koreeda simply feels elated by the story. “And that’s not because it’s critical of anything in particular … it’s celebrating these boys and what they found,” he says.

“The adults, on the other hand … the adults who are reaching out and trying to understand them get left behind in the process. So maybe it’s critical of that, but overall it’s celebrating the boys, who have left the adults behind, and are running towards their own happiness.”

Indeed, it’s often the adults that look foolish in Monster; the scene where Saori confronts the school principal and Hori almost plays like slapstick comedy.

“I was trying to say that even at the most serious moments, if you take a step back, there are some really strange and silly things happening,” says the director. “And that’s what makes it feel real, I think.

“So there are weird things happening in that moment – but that’s what’s real about it. So looking close up, it’s a tragedy but if you remove yourself it’s a comedy.”

It’s what makes watching Monster so interesting, with Koreeda deftly switching tone as events are replayed.

I was really proud that I got to work with him right at the very end

The last segment, for example, has the air of a melodrama, as the Yori/Minato relationship is deepened. Even the way characters are viewed subtly shifts.

In the aforementioned confrontation scene, Hori’s behaviour seems almost unhinged, until it’s replayed through his perspective.

“Because it’s a story about seeking the monster, when the point of view changes, the monster also shifts,” says Koreeda. “That was something I was very aware of.”

Sometimes, the director’s work is so subtle, it takes one of his performers to highlight it. Take the apartment where Minato and his mother live.

“One of the details he liked to pay attention to is where props are put,” says Ando, who plays the single mother. This includes “off-season” Christmas decorations. “In the script it’s not Christmas season at all,” she explains.

When she questioned it, a crew member pointed out that Koreeda took inspiration from a relative, who left the odd festive decoration up on the wall. “I think it’s just his way of expressing some details.”

Monster marks Koreeda’s first collaboration with the legendary Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, who died in March 2023. The director has been a fan ever since Sakamoto played in the pioneering band Yellow Magic Orchestra.

“He was kind of a star. And [his] film music, of course … this is something that I respect hugely, but also his stance on social issues. And the statements that he made – he’s kind of a really respected big brother for me, although we didn’t have a close relationship.”

About 10 years ago, Koreeda had a chance to work with Sakamoto on a project that ended up falling through. “I thought at that point, maybe I would never get the chance to work with him. But as I was in the process of making this film, he was the only person I had in mind for the soundtrack.

“And of course, he wasn’t well and so I thought it might be difficult, but I decided to write to him anyway. He watched what I put together and agreed to write some music for it. So I was really proud that I got to work with him right at the very end.”

(1).JPG?itok=0BHk6odg&v=1665981271)