How Chinese abstract artist Ding Yi turned crosses from a symbol of ‘criticism and denial’ into a tool of expression, as seen in Shenzhen retrospective

- Ding Yi has been painting canvases filled with plus signs and the letter x for 35 years, as seen in a retrospective at the Shenzhen Museum of Contemporary Art

- The exhibition shows how the artist went from pure abstraction to making references to the world around him – his native Shanghai, as well as Xinjiang and Tibet

Seeing artist Ding Yi’s retrospective in the futuristic Shenzhen Museum of Contemporary Art and Urban Planning, one has to marvel at the fact that the 61-year-old Shanghai native has laboriously sustained, for 35 years and counting, his practice of covering monumental paintings in tiny, hand-drawn plus signs and repetitions of the letter x.

This practice has been described as unvaried, but viewing around 60 examples from his “Appearances of Crosses” series under one roof offers dramatic proof of the shifts it has undergone.

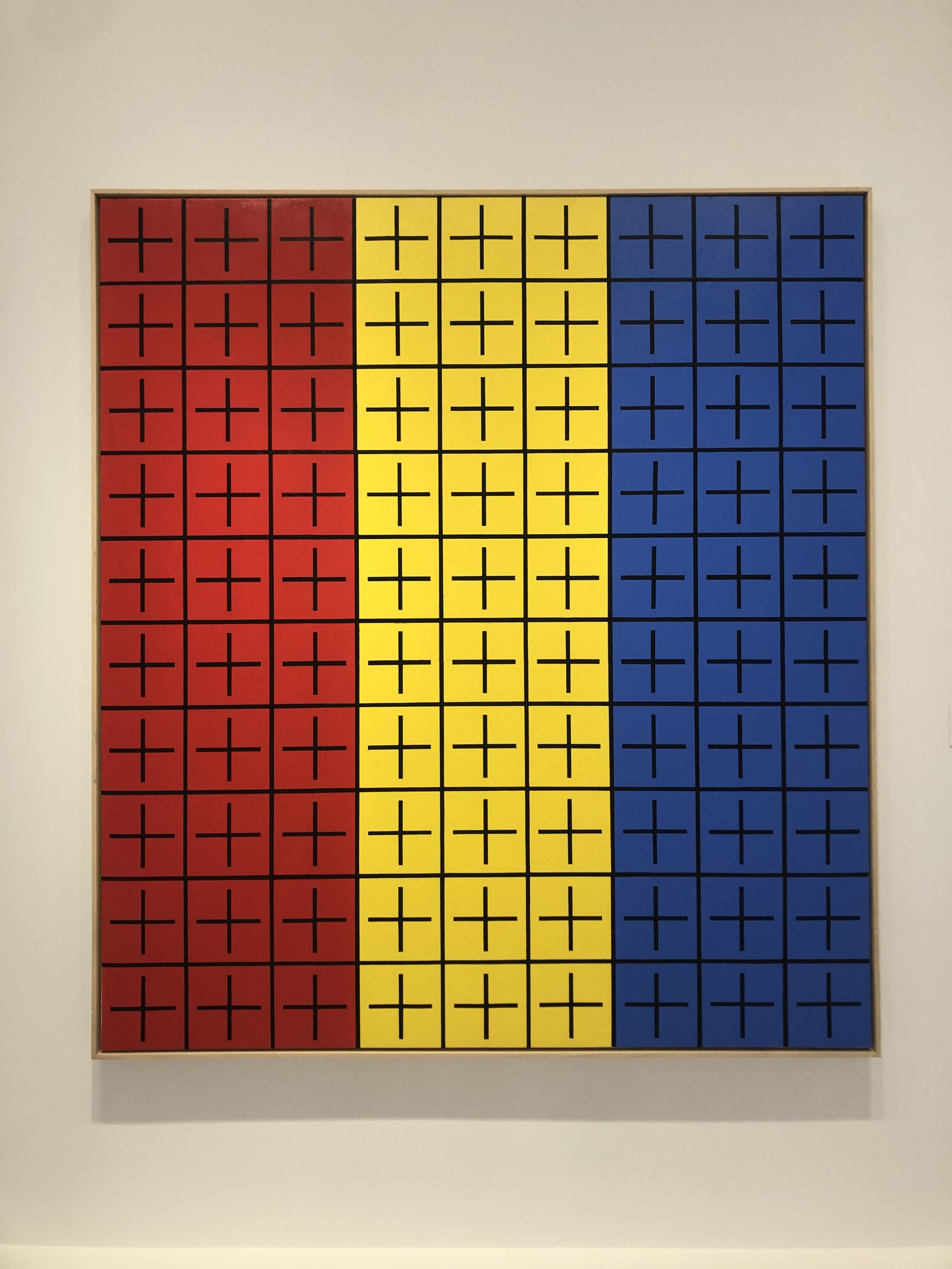

Called “Cross Galaxy”, the exhibition starts with a loud statement – a replica of Appearance of Crosses I hanging directly in front of the gallery entrance.

While the caption suggests it is the original from 1988 that Ding produced when he was a student in the Chinese painting department of Shanghai University, the show’s curator, Yongwoo Lee, clarifies that the old one is long gone and that this, and two other paintings from the same time, were repainted in 2020 and 2021.

The work is a near-square divided evenly into three vertical strips in red, yellow and blue. The acrylic surface is perfectly smooth, with little trace of the painter’s hand.

The tricolour background is further divided by black lines into a uniform grid of 90 squares, each with a plus sign inside just short of touching the edges.

In the late 1980s, after studying design as an undergraduate, Ding was sailing through a master’s degree in Chinese painting which mainly required students to mimic the works of elderly professors.

He changed his first name in 1986 from Rong, meaning prosperous, to Yi, a Chinese character written in one simple stroke which can mean either one or two, and which goes much better with the simplicity and openness of his art.

To us, the generation that grew up during the Cultural Revolution, crosses meant only one thing – criticism and denial

Now represented internationally by four art galleries, Ding says he was the odd one out among his fellow students.

Abstraction was not a mainstream choice at the time; most of his fellow students were turning the official, propagandistic style of Socialist realism on its head in what became known as the cynical realism movement, or appropriating cultural icons as “political pop”.

He, too, had once allowed the intense feelings of the time to show in his paintings. Next to the deliberate flatness of Appearance of Crosses I are two 1985-6 oil paintings, called Breaking the Sacrifice and Taboo, which are covered in crosses and blank squares in rough, furious brushstrokes against a stormy backdrop.

Chinese artist Yue Minjun’s NFTs: a parody or a response to market shift?

The artist, wearing his signature round glasses, his black hair in a bob, explains in Shenzhen that those earlier crosses were the products of an era of liberation after the Cultural Revolution.

But later, as other young artists filled their canvases with political meaning, Ding crossed out memory and context in his paintings and turned the symbols of denial into new tools.

To make something entirely new would require a steadfast and rational approach to abstraction that did not refer to real-life objects, a way of making art that didn’t look like art, and the wiping away of traditional baggage, he decided.

“That’s why, in the 1988 painting, I used the three primary colours. I wanted to say: ‘Let’s start from scratch!’” he says.

He kept his word for about 10 years, making “pure” abstractions that conflate art and design. Those works feature repetitive rows of plus signs and x’s – and asterisks where the two symbols cross – spread evenly across their canvases with no focal point or hierarchy, like the pattern of the tartan fabric that he would sometimes paint on.

‘Moving allows us to be fresh’: Hong Kong ‘travelling’ art gallery returns

Eventually, Ding decided to allow himself to make explicit references to the world around him.

“A new phase of the cross series began in the late 1990s. People kept asking me why my art didn’t reflect the changes in Shanghai. And so I started to make a record of the physical changes in the city,” he says.

The new wealth, material abundance and confidence of the time is apparent from the blast of bright hues in the exhibition’s “cityscapes” section. Ding calls them snapshots of his beloved hometown.

Hong Kong child of empire on his museum-like home full of Chinese textiles

The ones showing bright streaks zapping across a dark background, for example, could be night views of Shanghai, the city ablaze in raw energy.

They also hint at broader themes. The “artificial” fluorescent paint that he picked for this phase reflects the strangeness of the time, Ding says.

Among the most eye-catching of the works here is Appearances of Crosses 2008-21, a set of five dazzling red-and-gold square panels arranged to roughly suggest the outline of China.

He is increasingly drawn to that part of the world because he has been looking for a universal humanism beyond the values associated with the world’s dominant cultures, including his own, he says.

Unlike the rhizomic configuration of his earlier works, these 2023 paintings are strikingly binary. Two different shades of cinnabar red denote heaven and earth, Ding says, the two spheres connected by a shower of shooting stars.

Ding has always denied that his crosses are religious, and continues to maintain the apolitical nature of his art. So why is he connecting these paintings with the two autonomous regions in China that are most often associated with religion and politics?

Ding Yi’s art is about the universal law that is in all of us. The universe began with explosion, followed by expansion with time

“With age, I am not so determined to be removed from reality,” he says. The new paintings are not so much about the places themselves but meditations on individuals’ relationship with the collective, and their positions in history, he says.

Appearance of Crosses 2018-83 seems to be a monochrome galaxy filled with stars. On closer inspection, it is a giant Go chess board covered in white and black discs placed on top of a grid of crosses made with double lines in pencil.

‘I added red wine’: Hong Kong ink artist drunk on creativity in new show

Then there’s the Wind House, a room where ceiling fans covered in painted crosses are spinning, as if filling the air with the symbols.

Obliteration? Or palimpsests of history?

Chinese museums’ loan of art and artefacts to US counterpart is a landmark

“Ding Yi’s art is about the universal law that is in all of us. The universe began with explosion, followed by expansion with time,” says Gong Yan, director of Shanghai’s Power Station of Art, in a symposium held alongside the exhibition’s opening.

“He said he had to start at zero. And he has kept going, while continuing to use the same basic building blocks in new ways. To me, his art incorporates tradition, history and breakthroughs.”

“Ding Yi: Cross Galaxy”, Exhibition Hall A3, Museum of Contemporary Art and Urban Planning, Shenzhen, 184 Fuzhong Road, Futian Central District, Shenzhen, China, Tue-Sun, 10am-6pm. Until Oct. 15.