Central Asian hoard of avant-garde art from Soviet era draws belated attention, just as its visionary founder Igor Savitsky forecast decades ago

- Igor Savitsky amassed the biggest collection of Soviet-era avant-garde art outside St Petersburg in remote Nukus, Uzbekistan. The art world has woken up to it

- He foresaw ‘people from Paris’ would come to the museum he founded, and indeed it recently loaned works for exhibitions there. Its future is uncertain, though

Few visitors to Uzbekistan in Central Asia make it as far west as Nukus, a city whose rigid grid of streets reveals it to be the product of Soviet-era planning. Unlike ancient Samarkand, Bokhara and Khiva, it lacks warren-like old towns and ancient mosques, madrasas and minarets.

But distant Nukus is home to the snappily titled State Museum of Art of the Republic of Karakalpakstan Named For I. V. Savitsky.

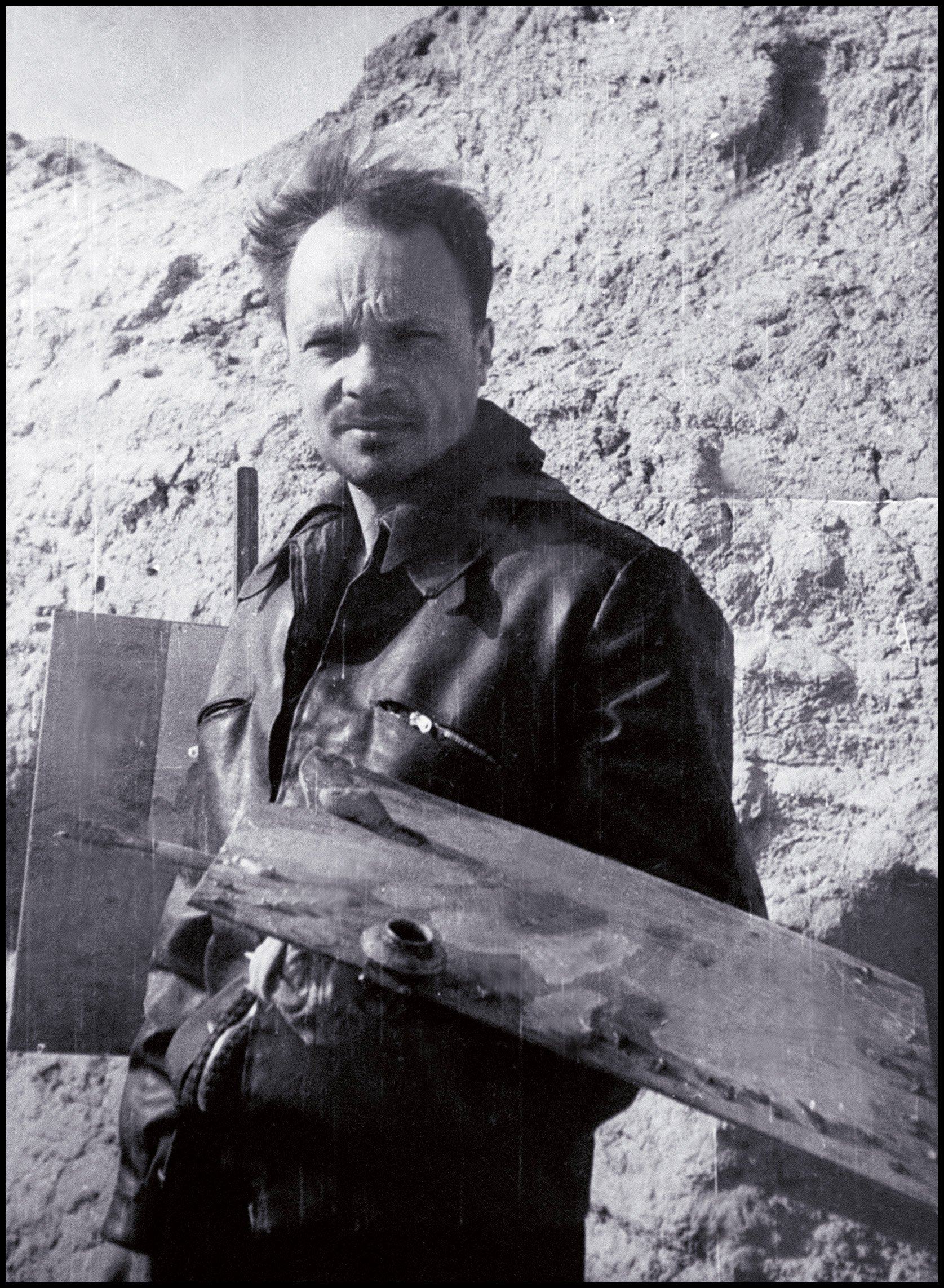

The city is the capital of the autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan, a large, mostly desert area that occupies the entire northwestern part of Uzbekistan. It was here that Igor Vitalievitch Savitsky (1915-84), an artist and collector born in Kyiv, now the capital of Ukraine, assembled a fabulous hoard of treasures in semi-secrecy and founded and led the museum, often referred to simply as the Nukus Museum.

Savitsky’s collection at the museum runs to tens of thousands of objects, and comprise archaeological artefacts dug up in the neighbouring desert, Karakalpak folk art, and 20th century avant-garde paintings despised by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, whose creators he often sent to the gulags, or simply had shot.

In attempting to preserve this last category, Savitsky risked the same fate. Yet here, astonishingly, is the largest collection of the Soviet-era avant-garde to be found outside St Petersburg in Russia, much of it rescued during Stalin’s lifetime.

Until recently, the collection was guarded zealously by Savitsky’s chosen successor, who was determined to keep it intact and in place. But, as Marinika Babanazarova tells me over tea in a Tashkent cafe, growing international recognition that the avant-garde art collection is as important as its location is remote only increases the demands that all or part of it be moved to a more high-profile location.

Some of the artists in the collection would probably have stayed in obscurity if not for Savitsky.

A graduate of Moscow’s Surikov Art Institute, he had joined the Khorezmian Archaeological Expedition in Karakalpakstan as an artist in 1950 and, living among the Karakalpak people, witnessed how Soviet-enforced uniformity was causing the decline of their culture. He began collecting traditional clothes, embroidery, jewellery and carpets.

When the size of the collection became unmanageable, Savitsky went to see local communist leader Kallibek Kamalov and asked him for the then astronomical sum of 3 million roubles to build a museum.

Kamalov was sympathetic, and Moscow far away. Although the project went directly against Stalin’s policies, the local leader secretly siphoned funds from elsewhere, and the museum opened in 1966.

By that time Savitsky, now teaching landscape painting in Nukus, had also discovered local artists who once painted in banned avant-garde styles with specifically Central Asian subjects.

In those times “avant garde” simply meant anything that Stalin didn’t like: Impressionism, expressionism, constructivism – in fact, any -ism that wasn’t the Soviet Socialist realism sanctioned in 1932 as a way to glorify the Communist Party.

In the Tea-House (1928), by Uzbek-born painter Alexander Volkov (1886-1957), shows Vladimir Lenin glowering down on a convivial gathering. But it wasn’t realistic enough for Soviet standards, so Savitsky quietly acquired the painting. Ural Tansykbaev (1904-74) came to be decorated by the Soviet Union for his realist paintings, but Savitsky persuaded him to reveal his earlier experimental works.

“I’ll take them all,” he said.

Babanazarova says Savitsky spent the last 18 years of his life collecting more widely. Travelling three days by train back to Moscow, he would visit artists or their families and discover banned art kept secreted away under sofas and in attics.

One such work is the The Bull, a playful construction of a horned beast with pitch-black staring eyes that is now an emblem of the museum.

The painting’s history was unknown until Babanazarova obtained access to KGB archives that revealed it to have been painted in the 1920s in Tashkent, now Uzbekistan’s capital, by Vasiliy Lysenko, who was sent to a labour camp in 1935 accused of counter-revolutionary activities.

This and hundreds of other paintings that Savitsky took in were in terrible condition, Babanazarova says.

“I worked with him for more than 10 years. He was a little bit crazy and a little bit genius,” says Aygul Pirnazarova, the museum’s head of applied folk arts, as she stands surrounded by samples of Karakalpak embroidery that Savitsky taught her how to preserve.

When Savitsky died in 1984, a victim of his casual approach to handling the toxic chemicals used in art restoration, Babanazarova, a curator from a prominent local family who had worked for Savitsky for years, succeeded him as museum director and discovered that only about half the collection had been paid for. The rest were acquired with IOUs.

A year later Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev launched perestroika, a period of reform that allowed previously banned art to come onto the open market, whereupon it soared in value.

“It was a hungry time,” Babanazarova recalls. Families of artists took the museum to court, and works that had not been paid for had to be returned; the museum spent about eight years sorting out debts. And this was not its only problem.

“I was pressed by local nationalists who said: ‘Why should we be so foolish like this Russian old guy? Stop buying this Russian art! Give them away!’”

After 31 years of preserving Savitsky’s memory she was suddenly removed from her post by the Karakalpakstan Ministry of Culture and Sports in 2015, which accused her of malfeasance.

The people from St Petersburg and Moscow were very arrogant with provincial museums

She and her supporters, including staff, families of artists and overseas patrons, strenuously denied the accusations and a long-winded investigation came to no conclusion.

Eventually, she was placed on the appraisal committee for appointing the current museum director, Tigran Mkrtychev, a Russian curator who began his three-year term in 2020.

The new director has had to cope with serious challenges, such as questions from the Friends of Nukus Museum (set up by overseas patrons) about the use of donations, and botched repairs he inherited from one of his predecessors which has halved display space until at least 2023.

European art masterpieces showing in Asia in ‘most ambitious project’ ever

Miyrigul Erekeeva, head of exhibitions, says tourism companies often complain. “They say ‘You have 100,000 objects in your collection and you show not more than one per cent in one building.’”

Alongside antiquities and exquisite crafts are works by artists who worked in soon-to-be-banned styles, mostly in the early Soviet years, with hints of Gauguin, Cézanne, Dalí and other European influences but with distinct local flavours.

“The artists were saturated with revolutionary ideas. That’s why those artworks that reached Europe were regarded as Russian art, not as European art, because they had their own topics,” says Erekeeva.

Mkrtychev told the Art Newspaper at the time of his appointment that he was keen to take the collection on tour, and Babanazarova herself has just attended Uzbek-related exhibitions at the Louvre and the Arab World Institute in Paris, both involving art loaned from the Nukus museum.

She clearly revels in the recognition the museum is now receiving.

“The people from St Petersburg and Moscow were very arrogant with provincial museums. They would say that Nukus is a collection of second- and third-rate paintings.”

China cosies up with Central Asian ‘stans’ as tensions rise with the West

To her satisfaction, there’s now much eating of words. But growing international recognition of the collection’s importance increases Babanazarova’s fears that works loaned overseas may be waylaid in Tashkent on their return.

Weeks after Savitsky’s death, she faced down an instruction from the central government to give up some objects permanently to the capital’s National Museum of Arts of Uzbekistan.

“I was not the director yet,” she recalls. “We were waiting for his body to be delivered to Nukus [for the funeral]. And they came to take some objects. I was fighting a lot not to give these objects, and wrote a letter to Moscow in order save these collections [for Nukus].”

These days, there is a growing appreciation of the collection’s potential to draw visitors and their money, especially since July’s rare protests against a now-withdrawn attempt to end Karakalpakstan’s autonomy which saw at least 18 people killed, according to Uzbek authorities, and a month-long state of emergency imposed.

New hotels and guest houses have opened, and there’s now a cafe opposite the museum which is probably the only place in town for a cappuccino.

“Savitsky would often say that one day people from Paris will be coming to Nukus to see this collection,” says Babanazarova.

At the time, even she laughed at him. But he has been proved right.