China is plugging pension hole by tapping into US$25 trillion in equity in state-owned enterprises

- Beijing wants to invest more of the national pension fund in China equity market to generate better returns than banks or government bonds

- SOE transfers and higher investment income are two of several methods government pursuing to plug hole in pension system

Every month, Liu Yuan sets aside around 900 yuan (US$131), or 8 per cent, of his salary to be paid into the public pension fund, while his employer contributes about 2,000 yuan.

These payments will guarantee the 33-year-old accountant of a construction company in eastern Shandong province a basic monthly pension payment of around 4,000 yuan a month when he retires in 25 years, all other things being equal.

But starting this May, his employer can cut the mandatory contribution to his account by about 200 yuan each month, as a new national policy to reduce the burden of social payments on companies takes effect. This could affect the future financial security of hundreds of millions of urban workers in the country.

The policy will cut employers’ pension contribution rate from as high as 20 per cent for each employee’s salary to 16 per cent that Beijing believes will help stabilise growth and employment as China faces its worst economic slowdown in decades amid an escalating trade war with the United States.

It also includes lowering companies’ mandatory contribution for the highest income earners, calculated based on a cap of no more than three times the average salary for the province or city, and for those who earned the least to draw more firms or self-employed people to contribute to the pension scheme.

“The policy [to cut contributions] is a necessary move to stabilise employment. It’s aimed at reducing companies’ burden and boosting their earnings, which are already struggling amid the economic downturn,” said Ma Wenyu, a macro analyst at Shenzhen-listed Shanxi Securities.

While the changes could take some heat off companies, the reduction in contributions to an already shrinking national pension fund raises more questions about China’s ability to provide retirement income to its rapidly ageing population among a shrinking labour force.

Shrinking pension fund

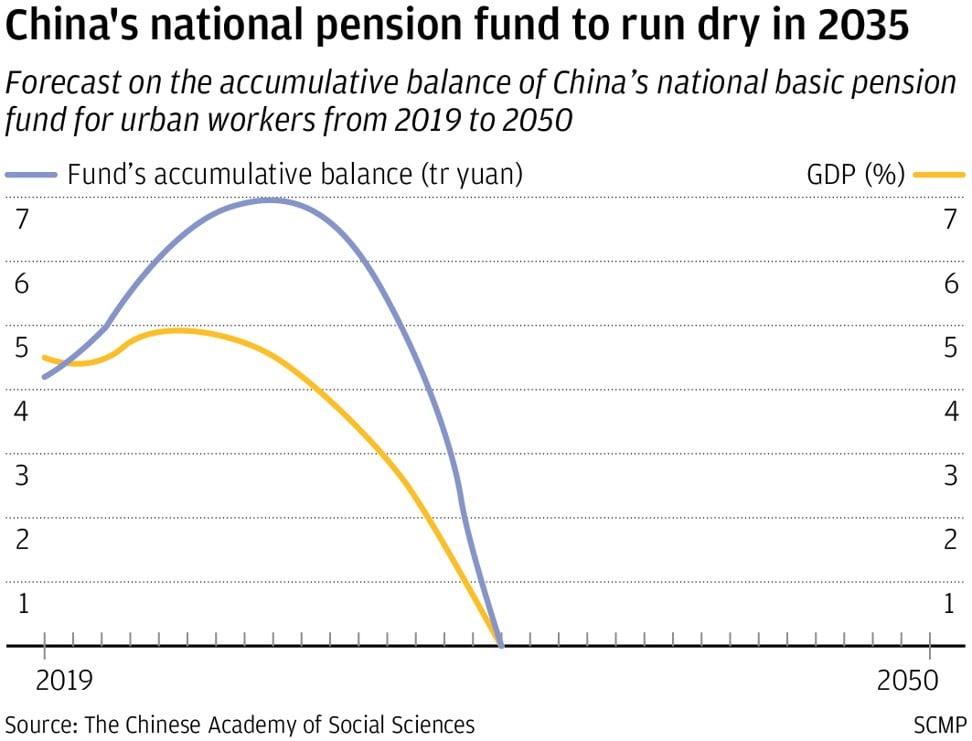

By the end of 2018, the fund held a reserve of 4.8 trillion yuan, according to its annual report. Last year, it received about 3.7 trillion yuan in new income, exceeding its 3.2 trillion yuan in outlays.

The new policy, however, will effectively slash the fund’s income and bring forward the time in which it starts to shrink to 2020, eight years ahead of what was previously estimated, according to calculations by Dong Keyong, a professor and director of the Pension Finance Research Centre at Renmin University of China.

The Chinese government has admitted that the new policy will worsen the strain on the fund, but promised to increase its income to offset the impact.

Among the ways are: raising capital through equity stake transfers from state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to the fund; increasing fiscal injections from richer provinces; and deepening reforms of the pension system to motivate more urban workers to join the scheme, according to a statement by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MHRSS) last month.

Beijing announced in November 2017 its intentions to shift 10 per cent of the equity of a few selected state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) – which oversees the pension fund. Since then, stakes in 18 central government-owned firms valued at a combined 75 billion yuan were transferred to the NSSF by the end of last year, according to the latest data from the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission.

They included a 10 per cent stake each in the country’s biggest casualty insurer People’s Insurance Company of China and its fourth largest life insurer China Taiping Insurance. The PICC stake was worth 32 billion yuan, based on the company’s A-share price on March 12 when the transfer of 2.99 billion shares was completed, and that for China Taiping, whose transfer is being processed, could be valued at HK$7.4 billion (US$942.8 million), based on a 10 per cent interest of its Hong Kong-listed unit.

The equity stakes in the 18 SOEs would have been less than 0.1 per cent of the 178.75 trillion yuan (US$25.97 trillion) of total assets, according to official data, held by China’s SOEs at the end of last year.

The policy [to cut social security contributions] is a necessary move to stabilise employment. It’s aimed at reducing companies’ burdens and boosting their earnings …

Beijing plans to expand the transfer scheme this year to include provincial and city government controlled companies. Several provinces like Yunnan, Sichuan, Xinjiang, and Anhui have published plans earlier this year to implement such transfers.

Difficulty in generating income

Despite government efforts to shore up the pension fund and expand revenue streams in recent years, experts remain concerned about the increasing difficulty it faces to raise enough funds to cover the country’s rapidly growing number of retirees.

Zhao Yayun, a researcher for Citic Foundation for Reform and Development Studies, said the central government should further increase the transfer of capital from SOEs, while also urging the fund to be more proactive investing in the capital markets to increase its income.

“The fund requires constant blood transfusions. But it also needs the ability to feed itself,” he said.

The NSSF published its first annual report in November, which showed the pension fund generating a return of 8.78 billion yuan, or 5.23 per cent, in 2017 on investments that included bank deposits, equities, bonds, pension products, securities investment funds, stock index futures and government bond futures in China.

In particular, investments related to equities, analysts said, were a concern given the volatility of the Chinese capital markets, compounded by the addition of the SOE stake transfers that increased the fund’s exposure in the markets.

As of April, the NSSF has become a top 10 shareholder of more than 300 listed companies, according to statistics from Shujubao, a Chinese financial data provider.

All of the six stocks that were added to its portfolio last year took a beating in 2018 as China’s major indices in Shanghai and Shenzhen recorded their worst performance in a decade, losing more than 24 per cent. Jiangsu Provincial Agricultural Reclamation and Development lost 53 per cent, Jiangxi Xinxin Industrial – 23 per cent, Guizhou Qianyuan Power – 16 per cent, Songcheng Performance – 14 per cent, Shenzhen Airport – 11 per cent and Joyoung – 6 per cent.

That said, the fund, analysts also pointed out, could afford to be more tolerant of short-term market fluctuations because of the nature of pension funds, which maintains a diversified portfolio of different asset classes for a better balance of risk and return over the long term.

“The pension fund has a strong characteristic – a long investment horizon,” said Xiong Jun, a fund manager and chief economist at Tianhong Asset Management. “That means it has a higher tolerance for risks and volatility. Even if asset prices fall [in the short-run], the fund is under no immediate pressure to cash out and suffer losses.”

By the end of the first quarter this year, the pension fund held 714 million shares of companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges, up 70 per cent from the 419 million shares at the end of 2018, according to data from the exchanges.

Reforming the pension system

To date, only 15 per cent of the pension fund’s balance has been invested, while the rest sits in banks or in government bonds with low returns, Tang Jisong, head of fund supervision unit at the MHRSS, said in February.

Tang said Beijing was encouraging local governments to invest more of the fund in the equity and bond markets as part of the drive to find new investment opportunities and design product portfolios that generate better returns.

“Investment returns will contribute increasingly more to the pension fund’s value in the longer run,” said Zheng Bingwen, director of Intentional Social Security Studies at CASS.

Equally critical to boost the fund’s sustainability, Zheng said, were reforms to raise the efficiency of pension system.

The current mandatory retirement age for ordinary workers is 60 for men and 50 for women, but 55 for female cadres employed in the government system.

The fund requires constant blood transfusions. But it also needs the ability to feed itself

According to the MHRSS’s 13th Five Year Plan (2016 to 2020), it plans to introduce a “progressively delayed retirement scheme” before 2020, in which the retirement age would increase gradually depending on when the employee was born.

For example, one proposal calls for men born in 1960 to delay their retirement age by six months. The delay for people born in 1961 will be 12 months, while those born in 1962 will be 18 months, and so on. Such adjustments would lessen the government’s pressure to pay out to the retirees all at the same time, and help uphold the promise to make full and timely payments over the long term.

“By cutting employers’ contributions, we are actually trying to encourage more companies and individuals to participate in the scheme and increase the total balance, thus making the cake bigger,”

Nie Mingjuan, head of the pension and insurance office at the MHRSS, said at a press conference last month.

Many small businesses, especially private firms, had opted out of the scheme because the previous contribution was too huge a burden to shoulder.

By the end of 2017, the national basic retirement fund covered 403 million people – 293 million urban employees and 110 million retirees, according to the latest statistics from the MHRSS in May last year.

More than 130 million urban workers remain uncovered.

Under the scheme, each retiree’s pension comprises two parts: money in the individual account and money in the social pool account. The money in each individual account came from the employee’s monthly contributions which he or she can claim upon retirement. But the social pool account is a pay-as-you-go account funded by employers’ contributions. This pool is used to pay out to current retirees.

Zheng suggested increasing the allocation of funds in the pension system to individual accounts, which are directly linked to employees’ future pension payments and would motivate more workers to join the scheme.

Liu the accountant said he was pessimistic about the outlook for his retirement.

“I’m working hard [to contribute to the fund] to provide for the elderly now. But when our generation of “post-80s” retire in 30 to 40 years, I’m afraid there will be no money [in the fund] to provide for us.”

There is good reason for Liu’s concern.

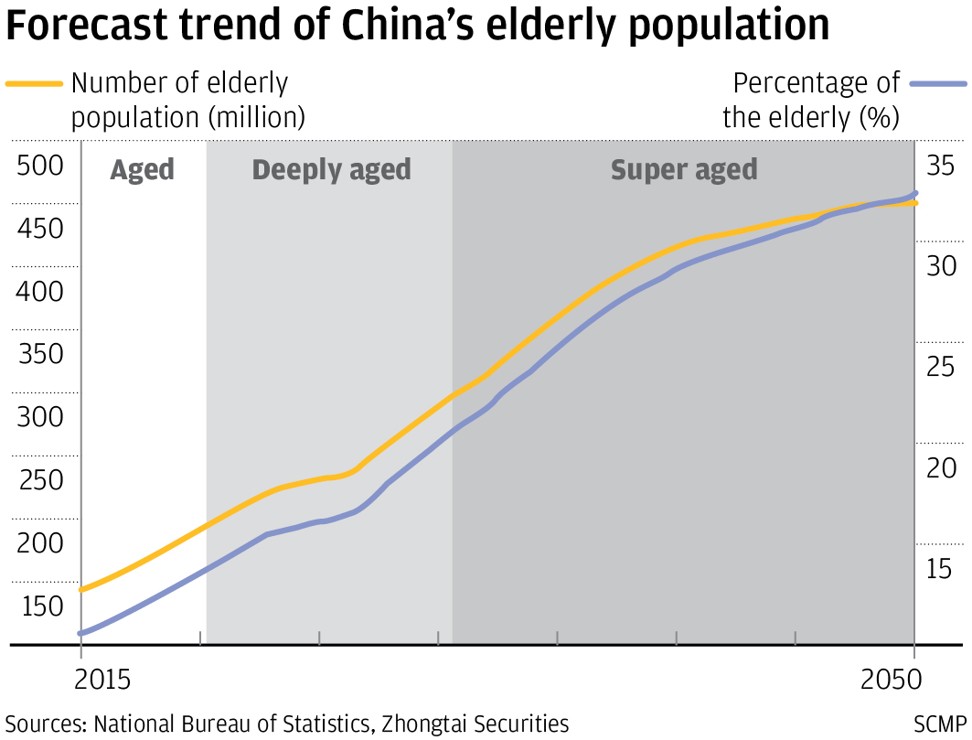

By the end of 2018, 17.9 per cent of China’s population, or 250 million people, were 60 years or older, an increase of 8.6 million from a year earlier, according to figures from the National Bureau of Statistics published in January. Some 11.9 per cent, or 167 million people, were above 65. Based on a forecast made in 2015 by the China National Committee on Ageing, the number of people above 60 will peak at 487 million in 2053, accounting for 34.8 per cent of the total population.

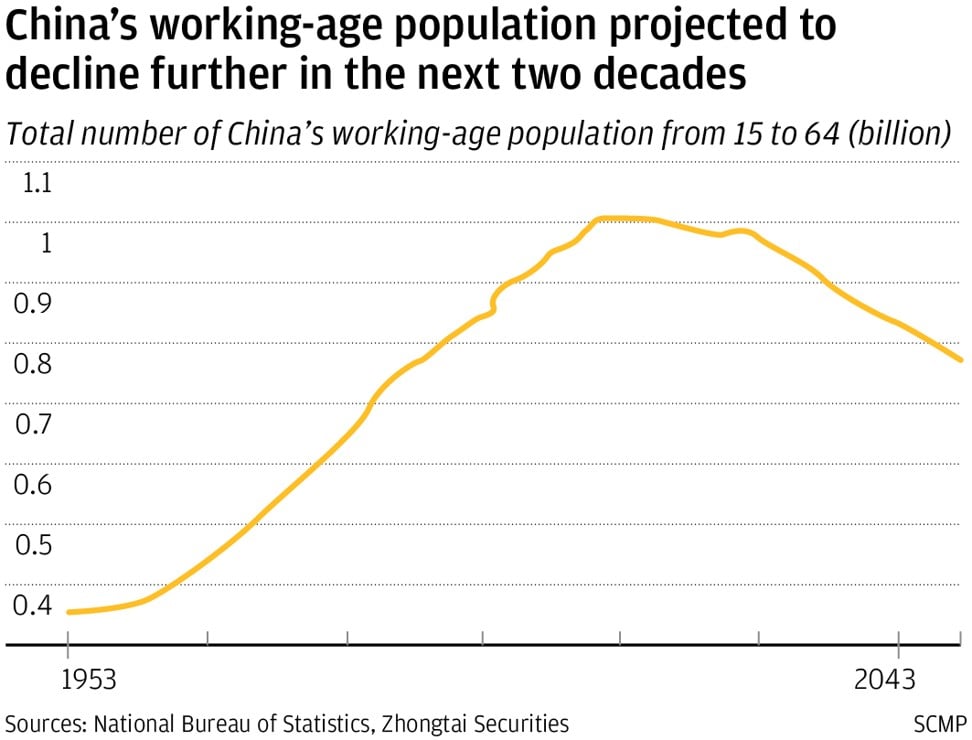

“Each of us young people has to now provide, on average, for 0.41 of an elderly person and a child, besides for ourselves,” wrote Liang Zhonghua, chief macro researcher for Zhongtai Securities, who is 31 years old, in a recent research report.

“But by 2030, each young person will have to provide for an average of 0.5 elderly and child. By 2050, the ratio will increase to 0.8, double the rate now,” he said.

“The burden will become heavier and heavier.”