Chongqing battles rising unemployment as China’s traditional industrial base follows nationwide slump

- The economy in the landlocked city grew just 6 per cent in 2018, its slowest pace since 1989, falling behind its own 8.5 per cent target

- Local government struggling to find jobs for residents and returning migrant workers who were laid off as the US-China trade war forced factories to downsize

With the Chinese economy slowing, concern has increased among Chinese policymakers about the outlook for employment, since ensuring sufficient employment is seen as a necessary ingredient in maintaining social stability in the country. Employment was the top priority the Politburo set last July when it shifted its economic policy focus to stabilising growth, leading the government to enact a series of policies to counter rising joblessness. This series will explore the employment challenges faced by different segments of the Chinese economy. This final instalment looks at the situation in China’s traditional industrial base of Chongqing.

The lights are out on a chilly Friday morning in January at the Zhicheng Job Centre, a once-bustling spot in the southwest of the city of Chongqing where recruiters used to come to find future employees. But on this occasion a four-hour job fair for marketing and services industries has been scrapped at the eleventh hour.

“No company has registered for this fair,” said a member of staff. “We have no choice but to cancel it.”

It is a far cry from the picture the job centre paints on its promotional brochure, with four job fairs planned every week across its 32,000 sq ft premises and 500 booths, potentially helping more than 200 companies connect with around 2,000 jobseekers.

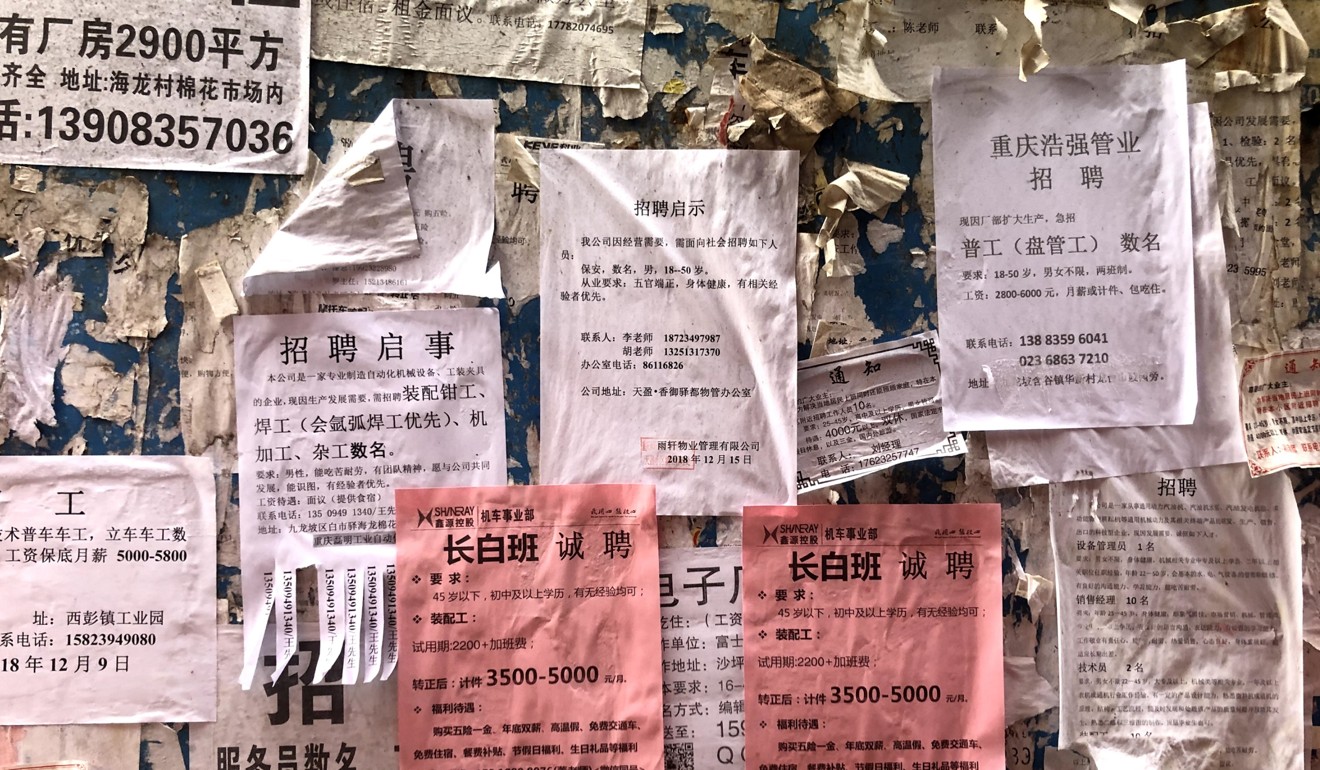

The local government has attempted to offset the cancellation of these large-scale job fairs across the city by organising smaller neighbourhood events, seeking to reassure the population even after growth in industrial output nosedived last year.

Until last year, economic expansion in hilly and landlocked Chongqing, China’s traditional industrial base, had surpassed the national pace in the last decade, and it was one of the fastest growing regions nationwide until the country’s overall slowdown.

Chongqing’s economy grew just 6 per cent in 2018, its slowest pace since 1989, falling behind its own 8.5 per cent target, which has put tremendous pressure on the local government to keep the population employed.

Local officials also need to accommodate returning migrant workers who lost their jobs when factory owners in export-driven coastal regions like Guangdong and Fujian provinces cut back amid a slowdown in demand caused by the US-China trade war.

Chongqing’s economic plight echoes the pressure that other inland provinces like neighbouring Sichuan face.

The city needs to create at least 800,000 new urban jobs this year to keep its unemployment rate “within a targeted range”, with a minimum of 600,000, director of the Employment Service Administration Bureau, Li Weimin, told the official Chongqing Daily in January.

Li said, on average, Chongqing needs to create 700,000 jobs per year.

While unemployment numbers in places like the United States are an important indicator for policymaking and follow economic cycles, China’s job data does not follow the same pattern.

The official unemployment rate in China’s urban areas was 3.8 per cent at the end of last year, while in a separate survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the figure was 4.9 per cent.

The NBS figure, covering 31 Chinese provincial capitals and municipalities, had remained unchanged at 4.7 per cent since September.

However, in figures released by the China Institute for Employment Research at Renmin University, the supply of jobs in major cities in western China, including Chongqing, fell by 77 per cent in the fourth quarter of last year compared to the same period in 2017.

The same research showed the supply of jobs in the east coast region dropped by 36 per cent, underlining the worsening unemployment situation nationwide.

Chongqing’s rising unemployment is largely the result of its declining industrial output growth, which last year slowed to a 30-year low of 3 per cent.

Production in its core car industry fell 17.3 per cent and growth in the electronics sector slowed by 14 per cent last year, the breadth of decline overshadowing the double-digit growth seen by its hi-tech industries.

To stave off the threat of rising unemployment, the city needs to increase investment in its industrial sector, which contributed more than 60 per cent to its gross domestic product in the past decade, said Ran Hong, deputy director of Chongqing branch of People’s Bank of China in a recent article published by the Chongqing Daily.

Carmaker Changan Ford is one of the city’s largest employers and the 50-50 joint venture between American giant Ford Motor Company and the state-owned Changan Automobile employs around 18,000 people, but has recently been forced to lay off contractors on its assembly line because of slow sales at the end of last year.

Contractors are hired on short-term contracts, offering more flexibility when demands decreases, but they do not receive the financial benefits or legal protections offered to full-time employees.

One senior technician at a Changan Ford factory, who did not want to be named, said that at least 130 “non-core” contractors had been fired, and those who stayed on could no longer work overtime to increase their income.

Changan Ford, when contacted by the South China Morning Post, did not mentioned the lay offs, saying it was reorganising its cost structure.

Many contractors from Changan Ford have been forced to look for temporary or part-time jobs until the Lunar New Year holiday, when factory recruitment typically resumes.

But these part-time posts, previously abundant at the Huibo Job Centre in the northern district of Chongqing, have recently been hard to find, and at its last job fair in mid-January before the centre closed for the Lunar New Year holiday, half the booths were empty.

A few jobseekers had gathered around a booth occupied by a security service firm, which was attempting to hire 60 guards to work eight-hour shifts, six days a week, with accommodation provided for a monthly salary of just below the official 2,907 yuan (US$431) average urban wage in Chongqing last year.

“If there is not so much work in the factories any more because of decline in manufacturing and export opportunities, what we have seen over the last few years is that laid-off factory workers go to the service sector, which is still expanding up to this point,” said Geoffrey Crothall, communication director from China Labour Bulletin, an Hong Kong-based non-governmental organisation that monitors labour rights.

“At the moment, the service sector is still be able to absorb a lot of laid-off people. The problem is that the jobs that are available are not necessarily very good jobs.

“They will be in transport, food delivery, courier driver … a lot of these jobs are very insecure, don’t necessarily pay very well. They can be laid off at any minute without any compensation.”

The surge in service jobs, particularly at small companies, has allowed urban employment growth to remain relatively stable even as China’s economy has slowed.

The employment sub-index in January’s Caixin composite Purchasing Managers’ Index, which mainly covers small private firms, showed that the workforce in the service industry grew, barely offsetting the downsizing witnessed in the manufacturing sector for the first time in eight months.

A monthly survey from the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business gauging more than 300 alumni, mostly executives at private companies, also showed their intentions to recruit staff had plunged to the worst level in six years since September last year and barely improved in January.

The challenge confronting Chongqing officials is how much the city’s rapidly growing service sector can soak up the increase in available labour, including returning migrant workers, even though their numbers have decreased since 2015 with factories in coastal cities moving inland.

One option is to encourage migrant workers to start their own businesses, with subsidies from the local government, but critics argue that such initiatives are attempts to cover up the depth of the jobless problem and could result in overinvestment in a particular sector.

Baishiyi, a dusty industry town of 44,000 people in Chongqing, is urging workers to “come home and build your own business.”

Huang Yunlian was one of many who responded to the call, and two years ago set up a business to produce components and spare car parts with his 50,000 yuan (US$7,412) of life savings.

“Without the government offering subsidies and championing success stories of entrepreneurs, many of us wouldn’t be excited enough to try [to form a new business]”, said the 33-year-old, who returned from working in Shenzhen.

“As proprietors, we would think: as long as I earn the same amount as I did as a migrant worker, I can keep the business going. But in reality, only a tiny number of people can even achieve that.”

Despite the economic slowdown, Huang was able to earn a net profit of 60,000 yuan (US$8,900) last year, as a downstream supplier to motorcycle and car manufacturers in Chongqing, compared with his bigger and highly leveraged rivals who suffered from poor cash flows as clients delayed payments.

“Businesses like mine are at the bottom of the supply chain. When times get tough, I can lower my prices to get by. But for factories in the upstream segment, they are burdened by the pain of a lot of debt,” he added.