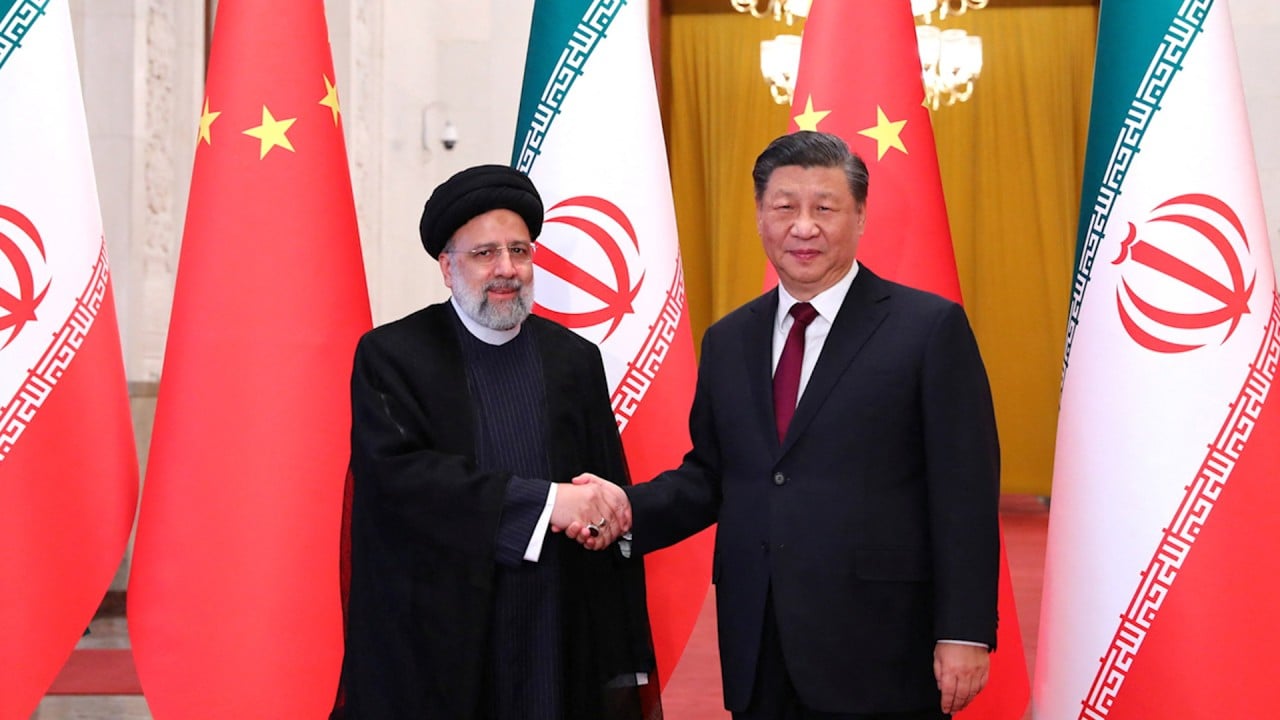

Power imbalance in China-Iran relations on full display during Raisi’s Beijing trip

- Sanctioned and isolated, Tehran has less to offer Beijing than Moscow, which can at least boast a powerful military and global presence

- Within Iran, there is also wariness of Chinese investment, and not even shared concerns about Afghanistan have helped to spur cooperation

In contrast, Iran is a heavily sanctioned and isolated power that produces little that Beijing immediately needs. Its rich hydrocarbon supplies are of interest to China, as is its large consumer population and open market for outside infrastructure investors. But these are all things that China can also find elsewhere.

Nowhere has this relatively limited dependence been on greater display than after President Xi Jinping visited the China-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) summit in Riyadh late last year. A joint communique issued after the summit highlighted GCC members’ concerns about Iranian behaviour in shared waters.

There is considerable resistance to China on the ground in Iran as well. In the wake of the announcement of the 25-year strategic partnership deal, a version of the document was leaked online, leading to a number of senior figures speaking out against it.

Former president Mahmoud Ahmedinejad, previously an eager ally of China’s when in power, expressed concern as part of his lobbying to return to power, recognising the public sentiment against the deal, while other senior leaders highlighted the plight of Uygurs as something the authorities should focus on with China.

Can China maintain balancing act in Middle East ties?

Both Israel and Saudi Arabia are implacable adversaries of Iran, and locked into confrontation with it in various locations around the world. Israel, in particular, has shown itself capable of reaching deep into Iran to go after specific individuals or targets.

In fact, the Taliban is often keen to highlight Iranian firms as alternatives to Chinese ones in their pursuit of external investment in the country. In other words, the one place where Chinese and Iranian direct interests collide, the two are in competition.

The reality is that the China-Iran relationship is as unbalanced as the China-Russia one, though the dependency from Iran’s direction is far more substantial. Moscow is as needy of Beijing, but in many ways has more cards that are useful to China. This power dynamic was on prominent display during this week’s visit, which was high on rhetoric with the substance still to be delivered.

Raffaello Pantucci is a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London and a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) in Singapore