Argentina’s Milei has a China conundrum of his own making on his hands

- To address a faltering economy, Argentina chose a leader who has vowed to cut the state’s role drastically

- However, international trade and investment demands substantial government involvement, and Buenos Aires can ill afford to jeopardise relations with a top trading partner like China

Argentina’s future stands at a crossroads, caught between Milei’s ideological aspirations and the practical realities of governance. A critical factor will be his willingness to push forward policies despite internal and external constraints, with profound implications for the region’s international orientation.

Such pronouncements underscore one of the many paradoxes of Milei’s rise: a pro-market leader potentially jeopardising relations with Argentina’s top two trading partners, Brazil and China.

Yet after the general elections, Milei has adjusted his public image, tempered his tone and begun to build connections with established politicians such as Patricia Bullrich, whom he had accused of being a “terrorist” in the 1970s.

The impending handover also marks a shift in Argentina’s political landscape, which has been dominated by the Peronist Party since the restoration of democracy in 1983. For the first time, a political group totally lacking executive experience is poised to occupy the highest office.

Despite securing victories in 21 out of 24 districts, Milei’s faction did not win any provincial governorships and will hold just 15 per cent of the seats in the Congress and over 10 per cent of the Senate. Not only will these minorities hinder any significant reforms, but they will also require a more strategic, pragmatic approach to governance.

Milei’s meteoric rise to political prominence raises concerns, particularly in areas that demand long-term, sustained strategies, such as diplomacy.

Since the election, he has subtly shifted his international stance without abandoning the cold war rhetoric. While emphasising his alignment with the so-called free world, such as the US and Israel, his budding administration has also said that the private sector can continue doing business with China and Brazil.

Diana Mondino, Milei’s primary international affairs adviser and likely future foreign minister, explained this diplomatic conundrum. Addressing business and political leaders, she said, “We will not break off relations”, but rather seek private partnerships over state-driven agreements. She repeated the same intentions in front of Chinese reporters who interviewed her in late November.

This posture is rooted in the ideological core of their political movement, which views the government and state apparatus as inherently corrupt and inefficient. As Milei said after his election victory: “Everything that can be privatised will be privatised.”

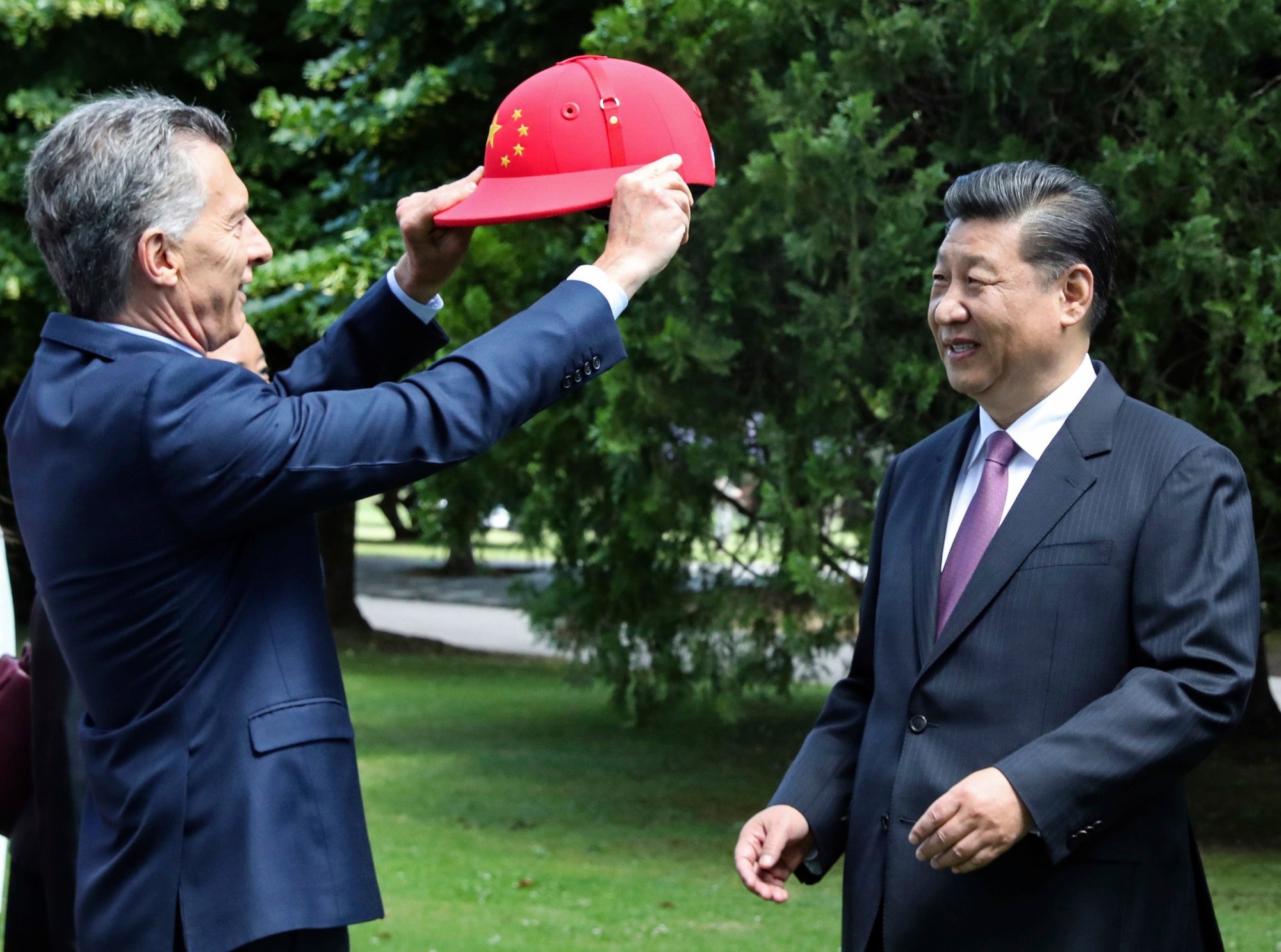

After the vote, Chinese President Xi Jinping offered his congratulations and Milei reciprocated by posting the letter on X (formerly Twitter), extending his good wishes to the Chinese population. In a meeting with Chinese ambassador Wang Wei, Mondino invited Xi to the inauguration ceremony – a move interpreted as an olive branch.

China has reaffirmed its willingness to work with Argentina, but pointed out that “no country could step out of diplomatic relations and still be able to engage in economic and trade cooperation”.

These disputes set the tone for the relationship. On the one hand, the efforts to de-escalate indicate an acknowledgement of Argentina’s dire economic situation. With more than 8 million children in poverty and an annual inflation rate of 142 per cent, Argentina simply cannot afford to lose its second largest trading partner.

Yet, Milei’s ideological convictions will wield significant influence on policy decisions. A striking irony becomes evident when considering his posture on China. Despite his advocacy of reduced state intervention, the reality of international trade and investment demands substantial government involvement.

Herein lies the central contradiction for Argentina: In seeking to address a faltering economy, the electorate has opted for a leader who wishes to reduce the state’s role in every aspect of life.

Milei thus stands as a transformative figure in Latin American politics, representing not only a pragmatic shift but also a broader ideological reorientation for a country familiar with radical fluctuations in both its economy and diplomacy.

Salvador Marinaro is an Argentine scholar and associate professor at Fudan University

.jpg?itok=Sfnz7QjB&v=1698126257)