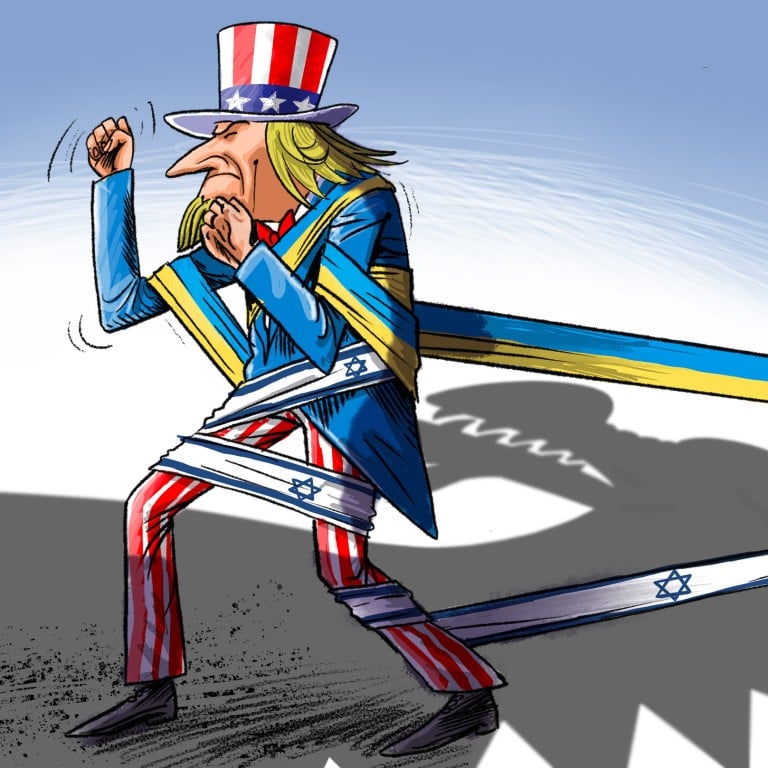

As war in Ukraine and Gaza rage on, can the US afford to take on China?

- Given its commitment in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, it is unclear how the United States can also sustain its rivalry with China

- Amid rising tensions in the South China Sea, frontline treaty allies such as the Philippines have grounds to worry about how ‘ironclad’ the relationship is

“The United States defence agreement with the Philippines is ironclad,” declared US President Joseph Biden amid rising tensions in the South China Sea. “Any attack on the Filipino aircraft, vessels or armed forces will invoke our mutual defence treaty with the Philippines.”

Economically, the Biden administration is yet to present a credible alternative to Beijing’s mega development initiative in Asia. Geopolitically, fear of strategic abandonment is gaining ground in the region, while China is well-placed to steal the march on the US.

After almost a century of global preponderance, America is facing the real prospect of “imperial overstretch”. As historian Paul Kennedy warned, great powers can decline and fall when the cost of maintaining their primacy outweighs their actual resources.

Like few contemporary leaders, Biden views his presidency in grand historical terms. He has also been compared with famous past American leaders. Amid the escalating conflict in the Middle East, Biden has channelled wartime presidents such as Woodrow Wilson, who sought to “make the world safe for democracy”, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, who famously described America as an “arsenal of democracy”.

Biden maintained that “American leadership is what holds the world together. American alliances are what keep us, America, safe”.

Accordingly, he called on the US legislature to double down on defence aid for foreign allies. The amounts being requested are staggering: US$14.3 billion in additional aid for Israel and US$61.4 billion for Ukraine, two nations that have already been major beneficiaries of American military assistance. Between 1951 and 2022, Israel received US$225.2 billion in US defence aid (on top of US$92.7 billion in economic aid). Ukraine has secured more than US$43 billion following Russia’s invasion last year.

These spending priorities are not in line with American public opinion, which tends to see China as the greatest threat to US primacy, ahead of Russia or any Middle Eastern power. Crucially, the real prospect of greater American involvement in the traditional strategic theatres of Europe and the Middle East has three major implications for Asia.

First of all, it may only reinforce lingering fears of strategic abandonment among frontline treaty allies such as the Philippines.

For almost half a century, various US administrations have refused to directly help the Philippines amid the latter’s maritime disputes with neighbouring states in the South China Sea.

In the 1970s, then US secretary of state Henry Kissinger argued in a diplomatic cable that “there are substantial doubts that [Philippine] military contingent on island in the Spratly group would come within protection of [Mutual Defence Treaty]” and firmly warned against allowing Manila to leverage its US alliance “for purpose of enlarging Philippine territory”.

Since 2015, the total US defence aid given to the Philippines has been barely more than US$1 billion, even as rivals in the South China Sea rapidly modernise their naval capabilities. The upshot is that Manila continues to depend on Washington militarily, especially in a South China Sea contingency.

South China Sea: collision takes three-way game of chicken closer to the brink

Finally, the US’ deepening military reinvolvement in regions such as the Middle East is bound to create greater discontent and anger among Muslim-majority nations, who have fretted over Washington’s categorical support for Israel through the decades.

And with an isolated Russia growing increasingly dependent on China’s goodwill, the Asian superpower has also become a vital player in determining the future of the Ukraine conflict. Far from containing China, the US is ending up with a formidable rival across the world.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China and the Struggle for Western Pacific, and the forthcoming Duterte’s Rise