Belt and road: West should work with China to build infrastructure – not against it

- After 10 years of the Belt and Road Initiative, the West seems to be finally getting its act together in finding financing for its infrastructure

- But it would be a pity if the largesse was used to compete with China, when the global scale of the challenge calls for cooperation

This is not the popular view, I know, but as someone long interested in infrastructure (my first editorial on the subject was published in 1966), I have respect for China’s initiative, despite its initial shortcomings.

Building physical infrastructure, whether in the form of highways, railways, ports or power systems, is a very costly undertaking, especially when it crosses borders. Governments and private investors shy away from it.

This was the situation in 1994 when I acted as chief external editor of the World Bank’s World Development Report on infrastructure, when the Washington Consensus strongly favoured private, not state, initiatives.

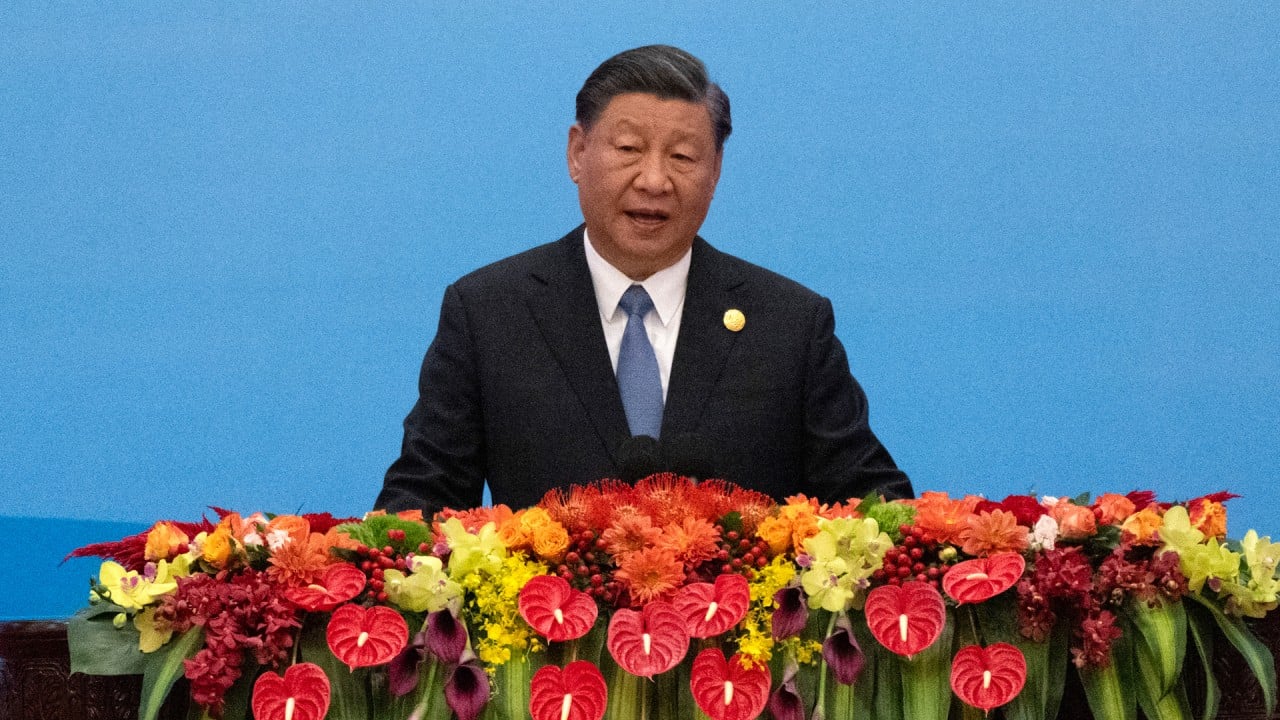

Then along came Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, proposing a remarkably bold venture for a hemisphere-spanning network of highways, sea lines and ports. It was breathtakingly imaginative.

The initiative should have been welcomed with open arms, not least in Europe. Here was an emerging Asian power offering to build highways and railways linking East and West, across the vast expanses of Central Asia and at vast cost to itself. Which other power was willing or able to do that?

The United States and Europe seemed stunned into silence for a while. Caught off guard, they reacted defensively even though the Belt and Road Initiative promised to give new impetus to global growth and development. Reasons were quickly found to oppose it.

China was perhaps at fault, however, in not preparing the ground more fully, in that its initiative was not provided with an institutional structure capable of accommodating multinational partners.

A multitude of economic powers might agree to participate but could not sign on to it in the formal sense via an international treaty and enjoy the power of voting on the initiative’s course and content.

But if China did not optimise the launch of the belt and road and AIIB to support what has since become a global competition to become the world’s top infrastructure power, rival nations have done even less well.

A plethora of international infrastructure initiatives, more remarkable for their sheer number than their efficacy, have since emerged involving the US, Japan, India, Australia and European powers in various combinations, most of them marriages of convenience or China-countering alliances.

The issue of financing is absolutely critical where infrastructure is concerned because of the huge sums involved in cross-border ventures, especially on the scale of the Belt and Road Initiative.

This realisation is finally dawning on Western powers, as evidenced by the belated conversion of key World Bank member governments to the idea that the bank should act as a leader, not a follower, of the private sector in infrastructure building.

This would give the (mainly Western) powers that control the World Bank, and some regional development banks, much more financial clout to tackle the global infrastructure challenge (as well as climate change and other big issues).

World is waking up to how development banks can fund social good

But it would be a pity, even a tragedy, if the World Bank family of development banks were to use this potential largesse to compete with China on infrastructure and in other socio-economic development areas.

Such is the scale of the challenge in providing the modern world – developing and advanced nations alike – with physical and digital infrastructure that we can hope to meet it only if national leaders stop playing politics with our future. They must be big enough to rise to the challenge in concert rather than in competition.

Anthony Rowley is a veteran journalist specialising in Asian economic and financial affairs