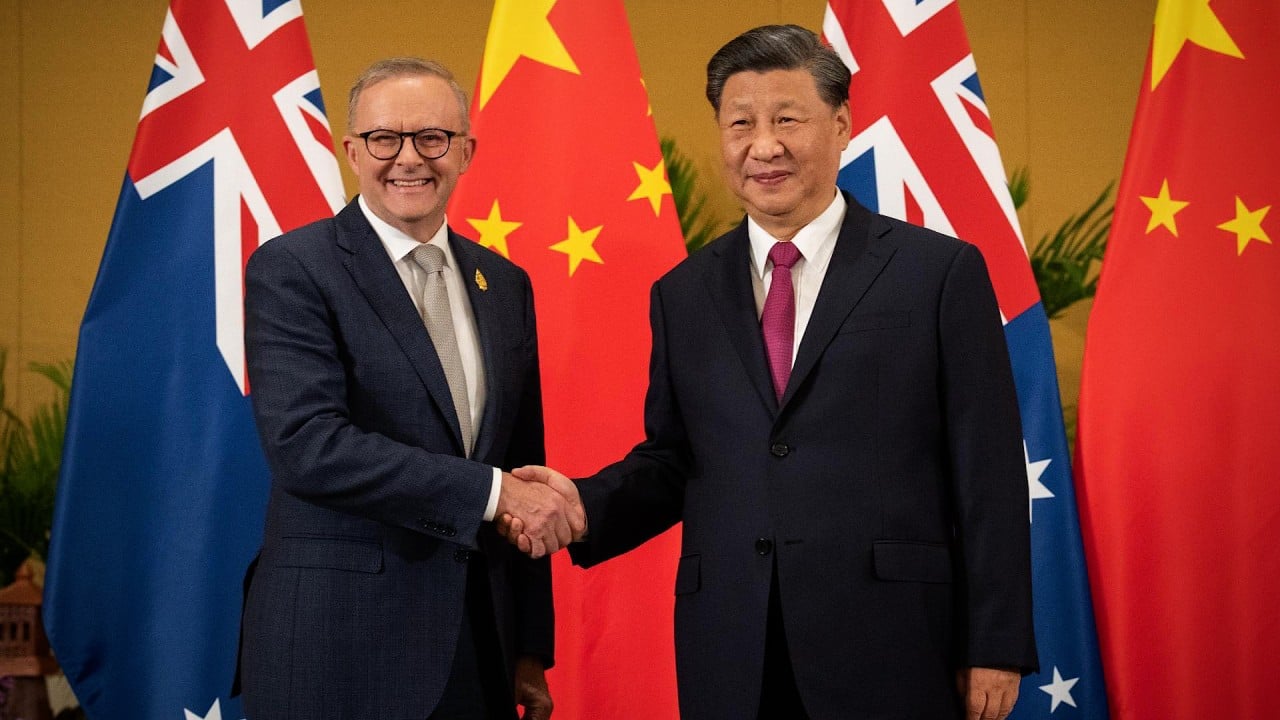

How Australia’s Albanese can get back to business as usual with China

- Geopolitics has got in the way of a potentially rewarding partnership between two economically complementary countries with no territorial or historical quarrels

- To mend ties with Beijing, Canberra must regain its strategic autonomy and shift away from the US policy of China containment

Towards the end of my stint as top economic diplomat at China’s Consulate-General in Sydney in May 2005, the Australia China Business Council held a farewell party in my honour. Addressing the gathering, I predicted that two-way trade between China and Australia would more than double between 2004 and 2009. My upbeat tone met with loud applause. And yet I sensed during the Q and A that some in the audience were not so optimistic.

My prediction was not a wild guess. It was based on an assessment of critical factors in bilateral commercial and economic ties.

On the other hand, China was well-placed to satisfy Australia’s need for a large number of finished products. Economically speaking, China and Australia were natural partners rather than competitors, much less adversaries.

The two countries are separated by the vast Pacific. They never had border clashes or territorial disputes. It would take quite a stretch of imagination to suggest that China would invade Australia or vice versa.

Besides, the two countries do not have any historical grievances; Australia was not part of the Eight-Nation Alliance that invaded China at the turn of the last century.

However, my prediction about Chinese-Australian trade was proved wrong. It took just three, not five years, for bilateral trade to more than double from a little over US$20 billion in 2004. Two-way trade topped US$43 billion in 2007. In 2009, it almost tripled to US$60 billion. New records were set year after year. In 2022, bilateral trade reached US$220.9 billion.

Today, all the factors in favour of robust economic ties between China and Australia remain unchanged – except the geopolitics.

What have the Chinese ever done for the Australians?

However, for Australia and China to enjoy stable and lasting relations, it would require a fundamental shift in Australia’s perception of China’s strategic orientation.

The current prevailing perception of China in Australia is not in line with reality. China seeks beneficial ties with Australia. As it is, coping with a Washington hell-bent on beating it takes up Beijing’s time and energy. Making Australia an enemy would not be in China’s strategic interest.

When the suspicion surrounding China is dispelled, Australia should see China’s economic development as an opportunity, rather than a threat.

For a structural change in the relationship, it is also crucial for Australia to have an independent foreign policy, reflecting Australia’s own strategic interest. It is no secret that the US means to contain China, and is getting its allies, including Australia, to fall in line.

While China is not about to ask Australia to sever its alliance with the US, it would be damaging to China-Australia ties if the alliance is used against China.

Does Australia really want to be at front line of US aggression against China?

An Australia serving as a foot soldier in the US geopolitical campaign can’t realistically expect business as usual with China; how many of us could be enthusiastic about doing business with a hostile party? Given that Australia enjoys a huge trade surplus with China (US$60 billion in 2021 alone), for China to be helping Australian exports grow would be akin to loading the opponent’s gun.

As Australia’s largest trading partner, China currently accounts for about 30 per cent of Australia’s global exports, and is likely to continue playing a crucial role in Australia’s future prosperity. If Australia is genuinely interested in constructive relations with the propeller of its economic growth, it will need to have strategic autonomy.

It is anachronistic to cling to an alliance forged more than 70 years ago, when many African and Asian countries were still in the shackles of colonialism and the US alone accounted for about 40 per cent of global gross domestic product. Times have changed. So has the global political and economic landscape.

Zhou Xiaoming is a senior fellow at the Centre for China and Globalisation in Beijing and a former deputy representative of China’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations Office in Geneva