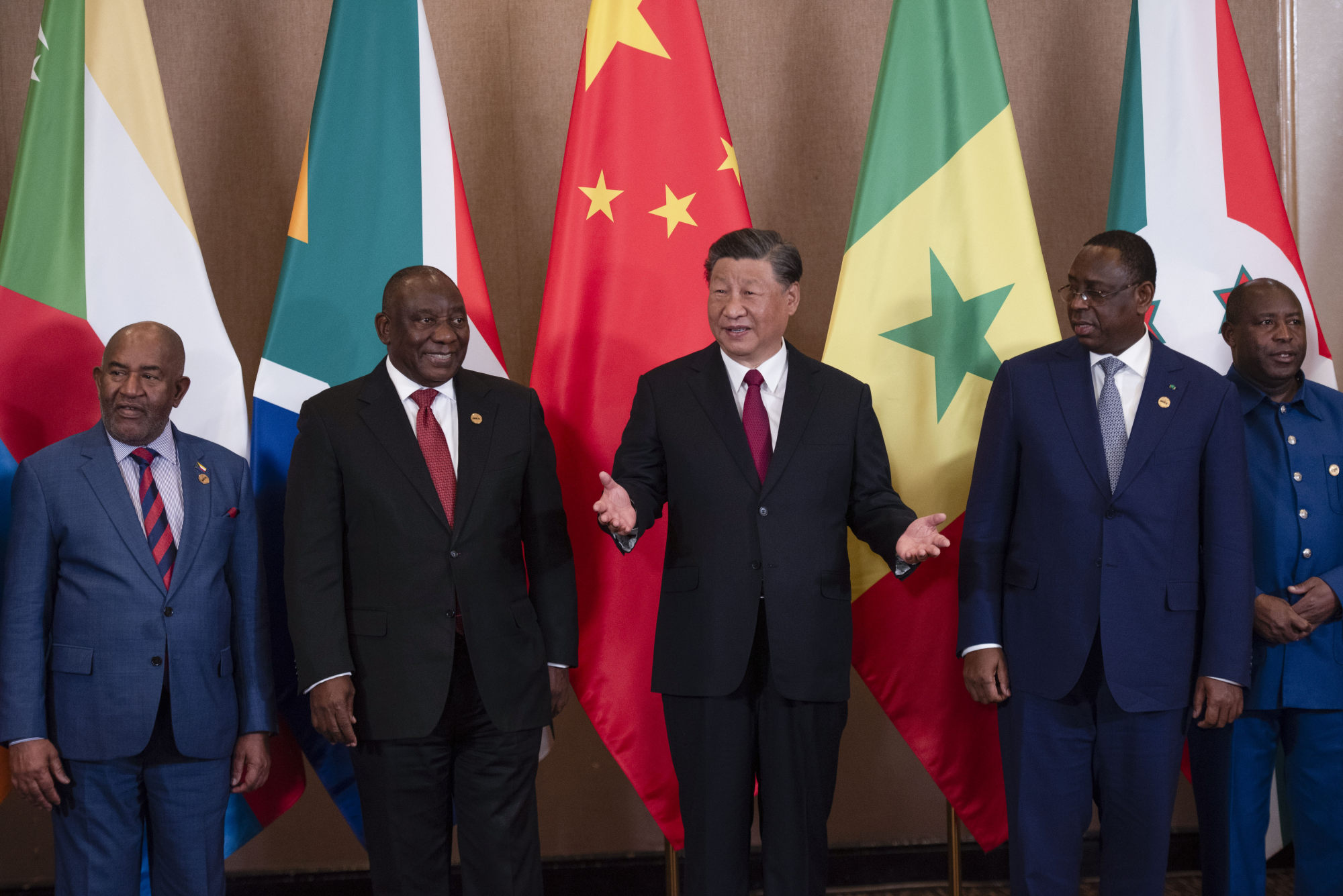

Expanded Brics’ key message: the West is not the only show in town

- The grouping seems too inherently illogical to be a threat, with core members in conflict and countries with vastly different economic, strategic and military weight

- But the point at the moment is about normalising a world order of institutions not led by the West

But this misses the bigger point of Brics and the other institutions that are characterised as being part of the new alternative order being pushed by Beijing in particular. At present, the point is not so much about creating real threats to the established institutions, but normalising a world order of institutions that is not led by the West.

The core idea is to preserve the world order that has been in existence since the end of World War II and was strengthened by the collapse of the Soviet Union. The barely hidden agenda is to freeze out authoritarian adversary powers like China and Russia.

Under the wider rubric of its Global Development Initiative, China is saying that the world does not need to be defined by the rules and order crafted by Western powers.

Western analysis struggles to explain this through the lens of action usually used to define international institutions. The fallback is to compare it to the Western institutions it seems to be competing against.

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation is often characterised as an “eastern Nato” and then derided for the general lack of tangible action. Yet, the SCO has ended up doing a lot under the radar.

From being a grouping that brought four Central Asian countries together with China and Russia to define borders and establish relations in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, it now has a collective land mass and population larger than any other regional organisation.

What Saudi SCO decision means for China’s influence in Middle East

It regularly brings together government ministers, businesspeople and the media from its member states. The SCO University, a network of existing universities, encourages student exchanges, while other programmes include gatherings of young business leaders, a film festival and marathon.

It conducts joint counterterrorism exercises, and the China National Institute for SCO International Exchange and Judicial Cooperation in Shanghai provides training and builds links among law enforcement agencies across the organisation.

Although the economic side is somewhat underdeveloped, the SCO has helped craft agreements to facilitate cross-border trade and developed common approaches to digital legislation and commerce among some members.

None of this is overtly game-changing but, cumulatively, it is substantial and highlights a path that could be followed. With member countries in conflict, a practice of not seeing the platform as their only vector of engagement offers appealing flexibility.

But this fluidity should not be mistaken for vacuity. It is normalising a world order that is not led by the West, the key point that China, India and others are eager to advance.

Raffaello Pantucci is a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London and a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) in Singapore