As warming ties with the Philippines show, the EU is quietly building a new golden age with Asean

- Far from a routine exchange of diplomatic niceties, recent developments in EU-Philippine relations reflect a broader geopolitical trend in Asean amid US-China jostling

- The EU’s constructive diplomacy has won Southeast Asian nations over, as economic synergies build trust and European strategic autonomy sits well with Asean neutrality

Other than taking a jab at Beijing, von der Leyen also underscored her commitment to pursuing a more comprehensive partnership with the Philippines. Accordingly, she unveiled economic grants and revived negotiations for a free-trade agreement.

Brussels is also expanding its strategic footprint in the Indo-Pacific to maximise economic opportunities and mitigate a Sino-American cold war in the world’s most consequential region.

Philippine-EU relations have been on a roller-coaster ride over the past decade. Under the reformist Benigno Aquino III administration, relations reached an apogee. Eager to tap European markets, the Aquino administration oversaw the lifting of bans on Philippine carriers and held off restrictions on Philippine fisheries’ exports.

On a 2014 trip to Brussels, Aquino said there was “no better time for us to build [a] strategically rounded partnership”, as trade and investment ties boomed. As a fellow democratic nation and a “new tiger” economy, the Philippines was also emerging as an attractive partner for Brussels.

During her visit to Malacañang Palace, von der Leyen underscored her commitment to accelerating “a new era of cooperation” as part of a broader effort aimed at jointly “strengthening our democracies” and preserving a “rules-based international order”.

On his part, Marcos hailed their “shared values of democracy” and emphasised his “desire to bring our bilateral relationship to greater heights”. Far from a routine exchange of diplomatic niceties, the warming of EU-Philippine strategic ties reflects a broader geopolitical trend in the region.

First, there is an emerging economic symbiosis between the EU and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Asean is the EU’s third-largest partner outside Europe after China and the United States, with bilateral trade reaching €271.8 billion (US$300 billion) last year.

Is China’s slice of export pie melting as geopolitical uncertainties heat up?

Similarly, the EU is Asean’s third-largest trading partner, accounting for a tenth of Southeast Asia’s trade. The picture is even more impressive on the investment front: the EU is Asean’s second-largest source of foreign direct investment with €350.1 billion in 2020.

With growing economic interdependence came greater strategic trust. The upshot is a shared appetite for deeper security partnership. In 2019, the EU signed a special defence pact with Vietnam, allowing the communist nation to participate in Europe’s crisis management operations as a special partner.

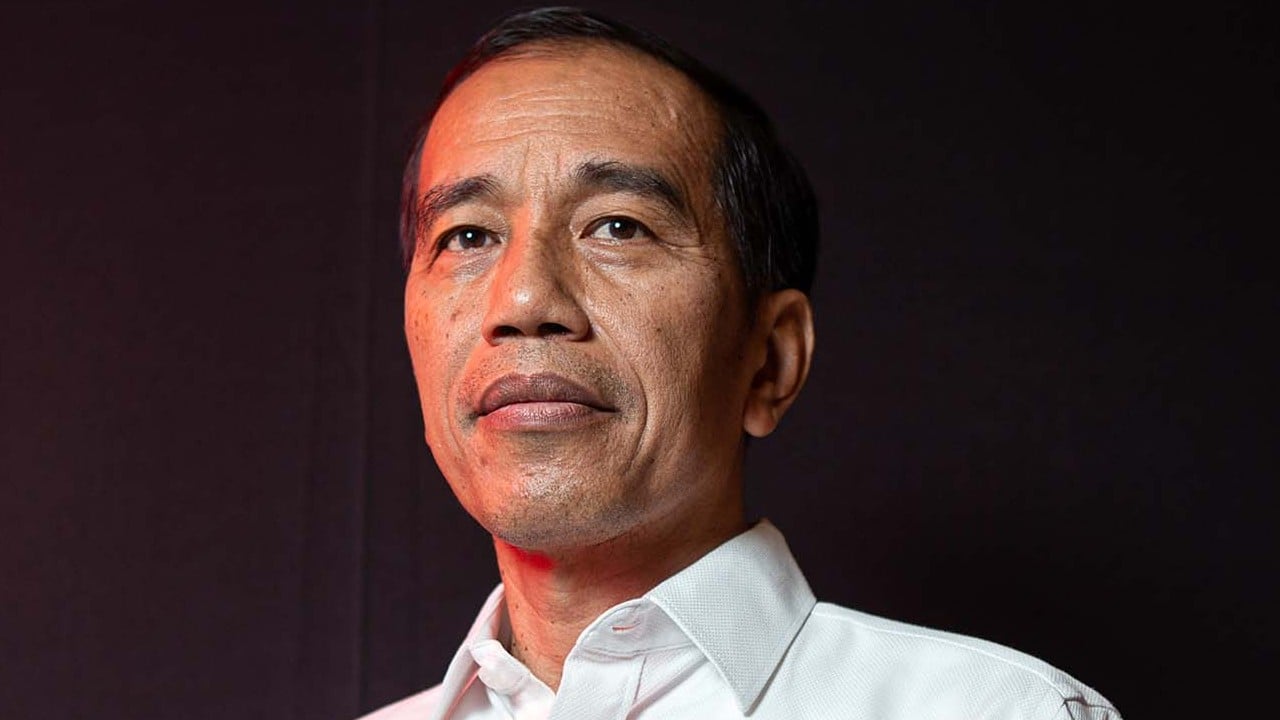

During her Manila trip, von der Leyen also offered security help to the Philippines, with a focus on strengthening its coastguard capabilities. The key European powers of France, Sweden, Spain and Germany, meanwhile, have been pursuing increased defence cooperation with the Philippines. The EU is also courting closer defence ties with Indonesia, Asean’s de facto leader.

Concerns over China’s increasing assertiveness in regional waters are a key driver of EU-Asean relations. But neither the EU nor Asean are in the mood to fully align with the US, which has ramped up sanctions and naval countermeasures against China.

How the Wagner revolt set back Macron’s vision of an autonomous Europe

But as French President Emmanuel Macron has made clear, the EU doesn’t want to play second fiddle to Washington, especially when dealing with China. After all, key European nations, especially Germany, are far more invested in expanding economic and strategic cooperation with the Asian powerhouse.

The EU’s constructive diplomacy has won Asean over. As a survey by a Singapore-based think tank shows, Southeast Asian policy elites view the EU as their top preferred “third party” partner, way ahead of Japan or India, amid growing concerns over the risks of Sino-American conflict in the region.

Steadily yet quietly, the EU is building a new golden age with Asean on their shared strategic interests and outlook.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China and the Struggle for Western Pacific, and the forthcoming Duterte’s Rise