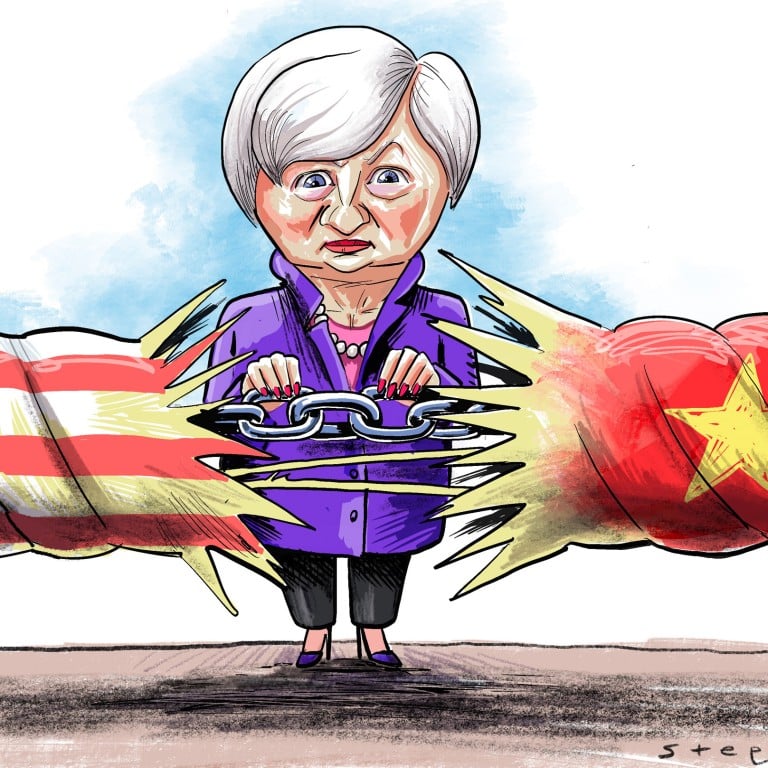

US-China relations: Yellen, Blinken meetings won’t fix weakening foundation

- A series of high-level meetings and positive rhetoric meant Yellen’s visit was encouraging to many, but the underpinnings of US-China tensions remain

- Leaders on both sides will have to expend significant political capital for a desperately needed diplomatic breakthrough in the near future

The Biden administration, meanwhile, has embraced a more protectionist approach to economics. As early as 2020, future national security advisor Jake Sullivan, then a top Biden aide, co-authored a report on how the US needed to embrace an aggressive economic strategy which both protects the middle class as well as ensures the country will maintain as large a lead as possible in cutting-edge industries.

Dump property or cut holidays? Middle class in China, US prepare for tough 2023

Aside from strengthening its economic foundations, the Biden administration has also unleashed a wave of sanctions targeting China’s cutting-edge industries. As a 2022 report from the Centre for Strategic and International Studies – a top US think tank – put it, what we are witnessing is nothing less than a “new US policy of actively strangling large segments of the Chinese technology industry”.

Even if the Biden administration loses power next year, there is little indications of a major reboot in US economic strategy. Republican strategists such as Elbridge Colby, who played a role in shaping the Trump administration’s national defence strategy, are calling for a whole-of-nation strategy that targets the foundations of China’s economic and military power.

This brings up the second major structural challenge: deepening public scepticism towards Sino-American detente in the near future. It appears the US policy elite’s view on China are shared by the broader populace. A Gallup poll published in March found that only 15 per cent of US respondents viewed China either very favourably or mostly favourably, with two-thirds of respondents seeing China as a “critical threat” to vital US interests.

Trump’s tariffs on China have cost the US, but they look likely to stay

The third, and perhaps most crucial, factor is the impact of US economic strategy on the geopolitical front. Beijing has repeatedly insisted that restoring institutionalised bilateral dialogue hinges on the removal of US sanctions which have not only targeted Chinese economic champions but also defence leadership.

In response, the Biden administration has maintained that diplomacy should come without preconditions, giving little indication of a significant compromise.

The upshot is the continued absence of fully functional military-to-military diplomacy even as the two superpowers continue to ramp up their naval presence in the South China Sea, Taiwan Strait and the broader Western Pacific. In short, leaders in both the US and China will have to expend significant political capital for a desperately needed diplomatic breakthrough in the near future.

Richard Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China and the Struggle for Western Pacific, and the forthcoming Duterte’s Rise