Law on my side: How Chinese are protesting against illegal local Covid-19 measures

- In a quiet revolution, lawyers, police and former judges are offering legal advice online, pointing out that many local measures violate government policies and laws

- These well-educated, legally literate people can act as a buffer in clashes between the masses and the party, challenging the party to course-correct when their interests are at stake

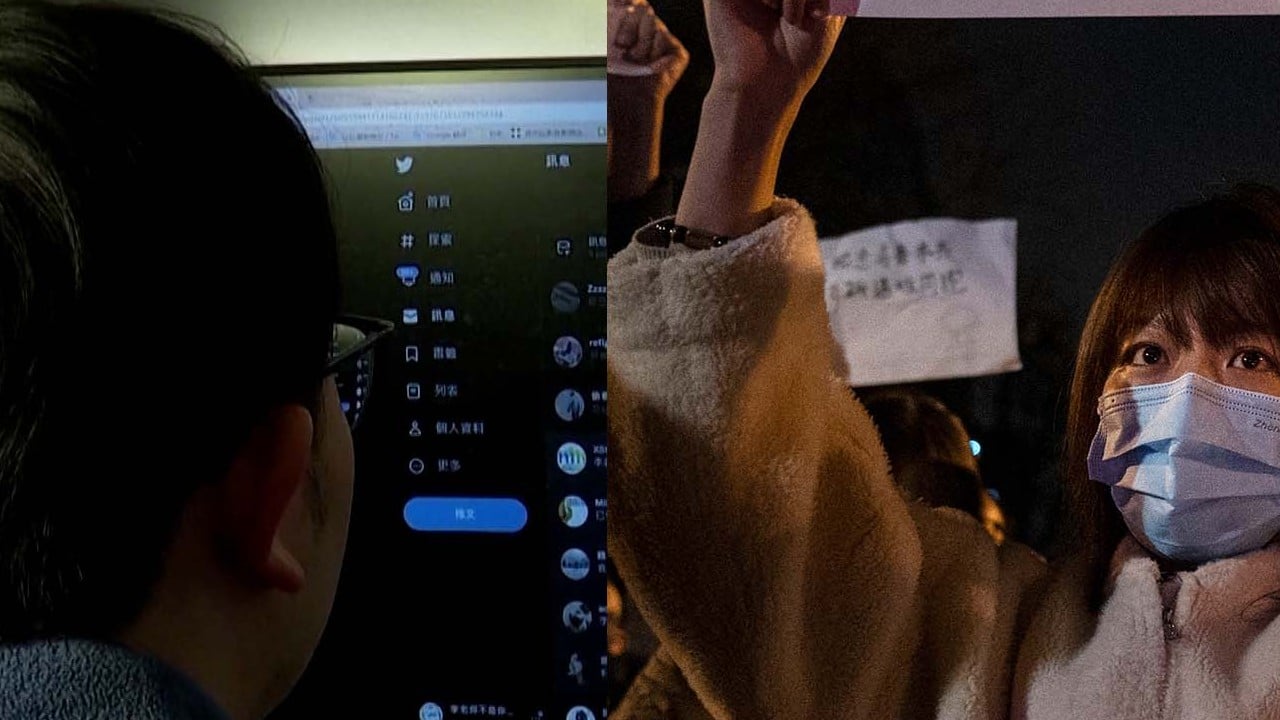

Their venues are not city streets but internet forums. Their objective: to teach ordinary Chinese about the laws that prohibit many of the worst behaviours experienced during lockdown.

These quiet activists include lawyers, police officers, professors and former judges. They comb through laws, and the constantly changing Covid-19 policies and local rules, to offer distressed citizens suggestions solidly grounded in law.

A lawyer invoked multiple laws to argue that, without approval from a county-level authority or higher, the police cannot arbitrarily check the contents of citizens’ mobile phones. In one case, a local police station in Zhejiang issued an apology and suspended an offending officer. Some experts even posted a chart of “guidelines for argument”, with step-by-step instructions on what to say when forced by the authorities into Covid-19 testing.

The weaponisation of the law against rights violations on this scale in China is unprecedented. There has been only one other national protest, in 1989, since the post-Cultural Revolution re-establishment of China’s legal system. But the current movement benefits from four conditions that did not exist in 1989.

First, China’s legislations are by far the most comprehensive since the establishment of the People’s Republic. It now has 293 national laws, 598 administrative regulations and over 13,000 local decrees.

Beijing has been touting the rule of law in recent years, even elevating it to the focal point of the Communist Party’s 2014 plenary session. In most people’s experience, rule of law is only rhetoric. China’s efforts in legal education, along with economic growth, have created a buffer between the party and ordinary folk.

Although the government is ruthless in repressing some dissent, especially challenges to one-party leadership and the one-China policy, it tolerates narrower criticisms that are fact-specific and law-based. It has allowed the circulation of articles and blog posts teaching people how to talk to “Big Whites” to prevent arbitrary quarantine, and how to invoke legal provisions to keep children at home.

The number of Chinese with a solid legal background is still rapidly increasing. The Ministry of Justice’s new five-year plan forecasts 750,000 lawyers by 2025. If China can stabilise its economy and recover from the pandemic, its middle class will also continue to expand.

These well-educated and legally literate people can act as a crucial buffer in clashes between the masses and the party. They can also challenge the party to course-correct when their interests are at stake. Right now, they feel their life over the past three years have been taken away. They are turning to the law to get it back.

Chi Yin, a former judge in China, is now an operations manager and a research scholar at the US-Asia Law Institute of New York University School of Law