How Hong Kong’s redevelopment projects can be showcases of ‘organic city’ growth

- The decision to bulldoze Kowloon Walled City in 1993 wasted a chance to turn the area into a cultural treasure that celebrates its history and character

- Instead of more cookie-cutter shopping centres and residential towers, Hong Kong needs development that evolves from the local characteristics of each district

When asked about “organic architecture”, the general public – as well as some architects – might have the false impression it involves structures built in organic shapes or resembling natural forms such as a flower, a seashell, an icicle or an animal.

Wright’s architecture went a step further, revealing how spaces could evolve and adapt. They are considered “organic” precisely because of their ability to grow like organisms.

According to Patricia Mooney-Melvin in The Organic City, a similar concept can apply to a city as “an organism composed of interdependent neighbourhoods”. Development would be decided at the local level by social planners and organisers as the implementation of these projects often faces challenges from city leaders and politicians.

London’s Notting Hill district used to be occupied by Caribbean immigrants in subdivided rental units, but it reinvented itself into a fashionable, must-visit neighbourhood lined with colourful Victorian town houses atop curbside cafes, bistros, craft shops and street markets. The area hosts the annual Notting Hill Carnival at the end of summer to celebrate the British West Indian community and cultural diversity.

How Singapore has become a garden city, but Hong Kong hasn’t

A contrasting example is the area just south of Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, which was heavily bombarded during World War II. The whole district had to be rebuilt from the ground up and became Potsdamer Platz. Currently, one sees a bustling business district with high-rise towers in glass, concrete and steel but without much cultural character or historical context.

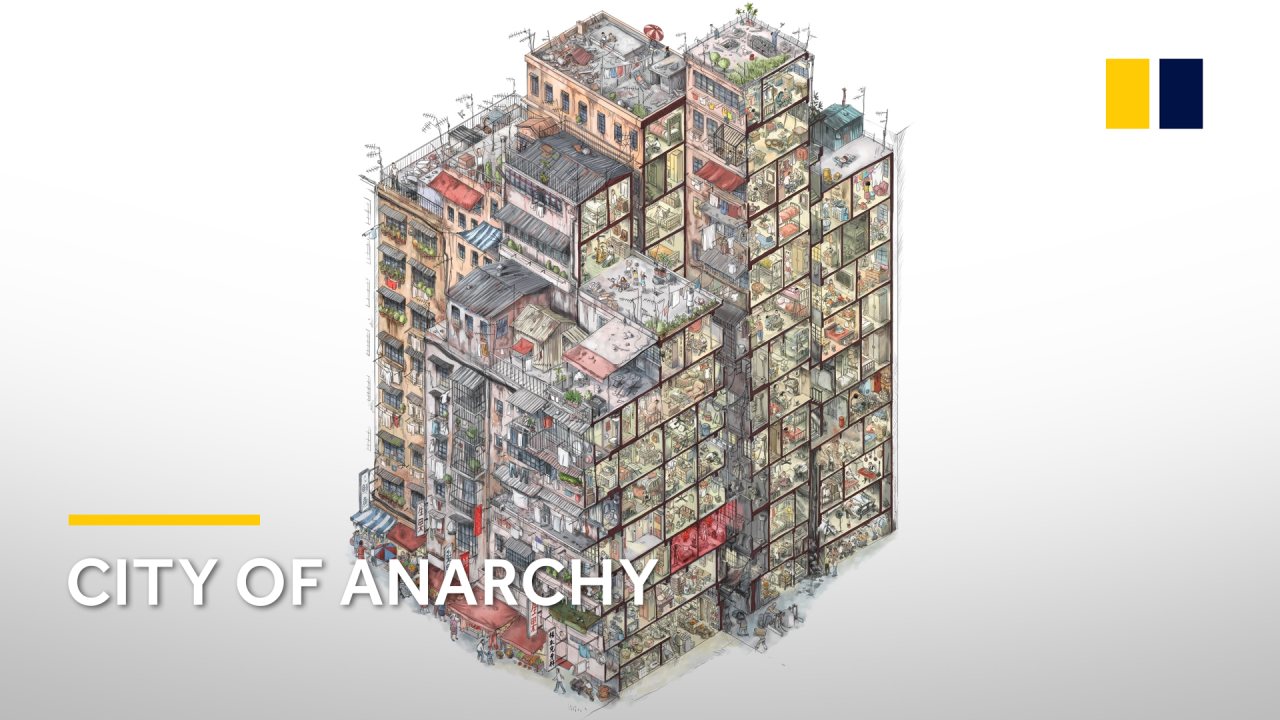

The Walled City could have been redeveloped in a more conceptually sophisticated way that preserved its character. We lost an opportunity to turn it from a dystopia into a cultural treasure.

Kowloon City once again appears to be under the knife, with the Urban Renewal Authority recently announcing a HK$15 billion (US$1.9 billion) redevelopment plan of the Lung Shing area covering more than 37,000 square metres and affecting hundreds of households and small businesses. Many low-rise tenement houses and ethnic businesses will not survive.

Wai Chi-sing, the Urban Renewal Authority’s managing director, said the plan was to avoid single-block projects and discourage “fragmentation” of the district, but this fails to recognise that fragments are precisely what a city is supposed to be made of.

Fragments are where we find cultural diversity, pockets of neighbourhoods, hidden treasures and a variety of experiences in a multilayered and multicultural city. Do we want all districts to look the same and all development to repeat an identical formula?

Organic growth does not mean out-of-control development. The government can provide formative guidelines and work with local neighbourhoods and residents on a vision for Kowloon City. The Urban Renewal Authority should thoroughly evaluate existing structures and retain as many as possible while holding owners and landlords responsible for complying with achievable safety and hygiene standards.

Such a unique experience cannot be airdropped into a district or implemented without understanding the underlying historic and cultural context of the place. Instead, it needs to grow from within.

To borrow the words of Alvar Aalto – another master architect who was once dubbed the “Finnish Frank Lloyd Wright” by The Wall Street Journal – “the very essence of architecture consists of a variety and development reminiscent of natural organic life. This is the only true style in architecture.”

Dennis Lee is a Hong Kong-born, America-licensed architect with 22 years of design experience in the US and China