Ukraine crisis: why Western sanctions against Russia are a double-edged sword

- Not only have US and European sanctions largely failed to make authoritarian governments toe the line, they have further entrenched those regimes and fuelled an East-West geopolitical rift

- With the West’s influence waning, reviving dialogue with countries that do not share its norms may be the only way out

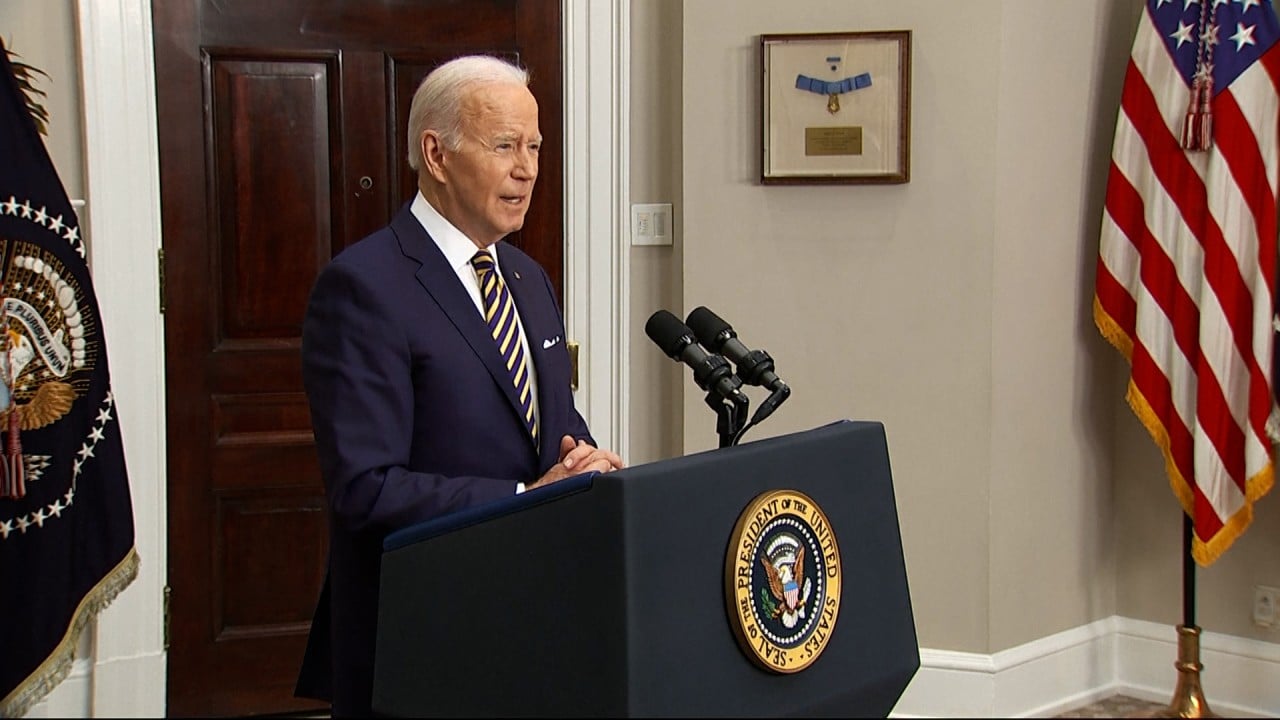

Short of outright military confrontation, economic sanctions are as far as the US and its allies can go towards punishing Moscow. For years now, in the aftermath of the debacles in Iraq and Afghanistan, successive US presidents have favoured sanctions as a coercive tool.

In 2017, US president Donald Trump added nearly 30 per cent more individuals and entities to the US sanctions list than his predecessor Barack Obama had done in his last year. Obama had added nearly three times as many in his last year in office as he had in 2009.

Yet, despite their growing popularity in war-weary Washington, sanctions have largely failed to achieve their goals, whether in North Korea, Venezuela, Iran or elsewhere. Instead, they have left long-term consequences for the world at large.

That is significantly lower than Western currencies, but as Western sanctions continue to target authoritarian regimes everywhere, Beijing will seek to fill the gap.

The absence of cooperation from China and Russia has also rendered Western sanctions less effective. In 2021, China imported 324 million barrels of crude from Iran and Venezuela on the cheap, skirting sanctions by often rebranding the imports as oil from Oman or Malaysia.

How sanctions on Russia risk mass destruction of the global economy

Without the means of basic survival, most people are unable to keep protest movements going, and as a result, regimes become more deeply entrenched over time. In 2019, a report by the Washington-based Centre for Economic and Policy Research estimated that 40,000 Venezuelans died as a result of sanctions imposed by the Trump administration in 2017.

Then, government propaganda, which paints the West as an uncompromising enemy, also begins to succeed. In Venezuela, for instance, President Nicolas Maduro had reigned over economic mismanagement even before the US imposed sanctions on his country. Yet, sanctions helped Maduro deflect the blame, and in 2019, one poll found that a whopping 68 per cent of his people blamed the US for their poor quality of life.

For Washington, all this has also comes with significant geopolitical costs. As America’s unilateral clout has declined, its power to build global consensus against repressive regimes and human rights violations has also declined.

Don’t sabotage Iran nuclear deal, West warns Russia

The long-term cost for the West is not only that it is unable to secure consensus – and thereby demonstrate leadership – but also that sanctions progressively diminish its own economic leverage, as each of these countries gets increasingly disconnected from the West and more reliant on China.

Under these circumstances, rather than imposing wide-ranging sanctions everywhere, the West should pursue deeper and more frequent East-West dialogue on international norms, especially with countries with which it does not share those norms.

If it comes down to a China bloc vs US bloc, who stands to gain the most?

But that left out several important countries and only played into the narrative of an East-West clash – an argument that many authoritarian regimes use in their domestic propaganda to drum up support against the West.

Admittedly, in the midst of Russia’s unilateral aggression against Ukraine, some might find a call for broad-based dialogue feckless. But in a world in which the West is progressively losing its clout, and sanctions are causing more harm than good, reviving multilateral dialogue may be the only way to get things done.

Mohamed Zeeshan is a foreign affairs columnist and the author of Flying Blind: India’s Quest for Global Leadership