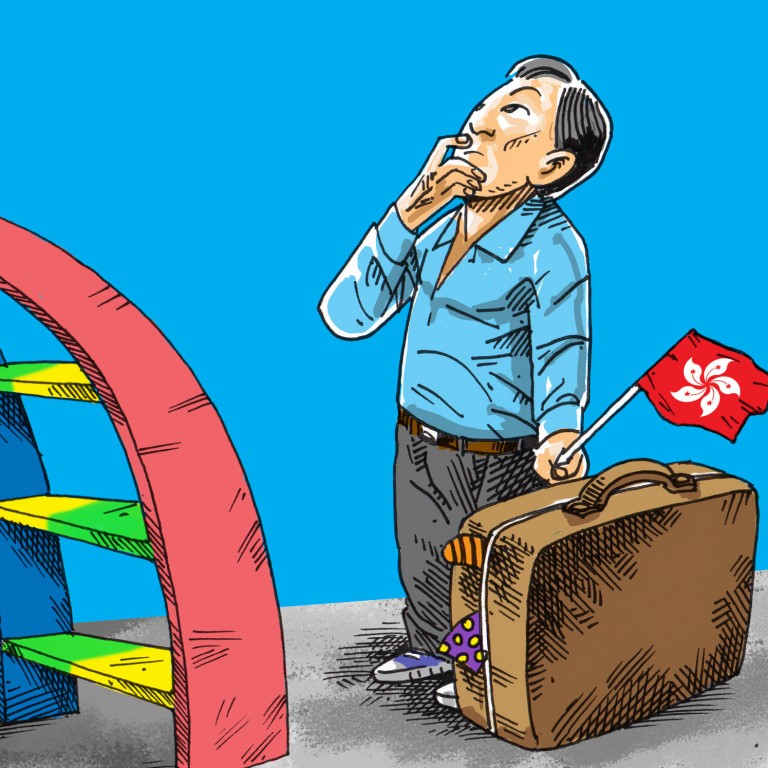

Hong Kong exodus: those who choose to stay need to decide where their loyalties lie

- It is not surprising to see many people leaving the city after the events of the past two years as history shows flight is in Hongkongers’ DNA

- For those committed to the city, it is time to help rebuild for the long-term future as part of China

Hong Kong people have flight in their DNA. This is not surprising in light of the city’s complicated history, but now that Hong Kong has been a part of China again for more than two decades, the people of this city need to reflect on the meaning of citizenship.

Hong Kong’s population increased quickly from about 2 million to 4.5 million between 1950 and after the tumultuous Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. The population had grown to almost 4.7 million by 1978 on the eve of China adopting its new policy to pursue development in earnest.

It is common for Hong Kong families to have relatives living overseas. For example, many who left the mainland after 1949 went further afield because Hong Kong was considered too close to China. Most who left saw the Maoist era in a very poor light.

People were desperate to get foreign passports. Wealthier people paid to obtain passports and residence rights in multiple jurisdictions to hedge their bets. Most preferred English-speaking countries – Australia, Britain, Canada and the United States – which were seen to be economically advanced and offered good education for their children.

Liberal democracies also demand loyalty of opposition parties. But, for Hong Kong people, some see such a demand as suffocating if their basic outlook cannot accommodate what they see as an illiberal China.

As a colonial administration, the pre-1997 British authorities did not require demonstrations of loyalty from ordinary people. Schools did not have to perform flag-raising ceremonies, and no one had to learn to sing the British national anthem.

As China turns inwards, Hong Kong’s global outlook fades

The protests in 2019 became calls for independence by some groups during the upheaval. Seeing legislators and well-known activists running to other countries to call for sanctions were among the reasons for Beijing to pass the national security law and impose it on Hong Kong without consultation.

Hong Kong has stepped into a period in which its people are having to reflect on their sense of political loyalty. Being a patriot cannot mean always agreeing with the local or national authorities, but the national security law has spelled out activities that endanger state security, which in political and legal terms represent red lines not to be crossed.

Hongkongers had the best of all worlds, but the protests of 2019 to achieve political purposes have changed that early liberal attitude from Beijing.

For some, flight seems to be the best option. For those who stay, it is time to rebuild Hong Kong for the long-term future as part of China.

Christine Loh, a former undersecretary for the environment, is an adjunct professor at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology