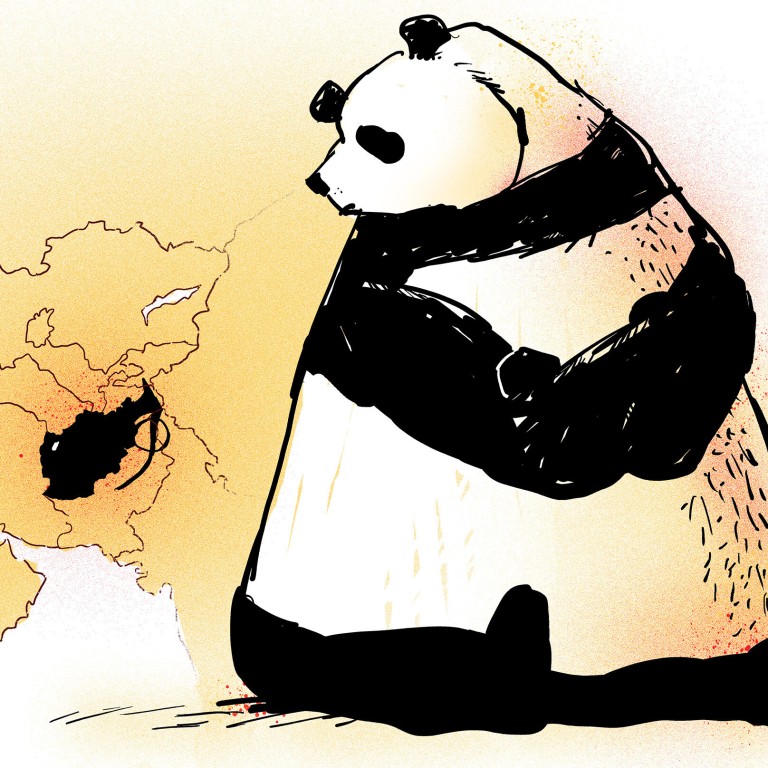

Time for China to stop hedging its bets in Afghanistan

- The flak Beijing has drawn for its Taliban engagement is not just unfair but also misses the point. If China’s Afghan strategy is to be faulted, it’s for doing too little

- China has the influence and tools – not to mention incentive, as Afghanistan’s neighbour – to take a leading role in fostering peace

Where China could be accused of failing Afghanistan is in not stepping forward to take a more proactive role in fostering an agreement, rather than simply waiting for some resolution to work itself out through bloodshed. As it turns out, this is also an echo of the approach Washington has decided to take.

The exaggerated narratives around Chinese potential economic plundering of Afghanistan have not played out as predicted. This, it should be noted, is much to the chagrin of the former government in Kabul, which would have loved to get the tax and investment benefits from the exploitation of the country’s natural wealth.

All of this is a reflection that Beijing does not trust the Taliban any more than the US or anyone else does.

This is often its main point of discussion when it focuses on Afghanistan. And it is likely to be the primary concern that Beijing worries about now it has new interlocutors in Kabul.

Beijing has also engaged in multilateral diplomacy of all kinds. It has played a limited role in some of the larger international engagements around Afghanistan, offering some support and money during international donor aid rounds.

It has fostered regional multilateral engagements, and has used Afghanistan as a point of engagement with its adversaries – both Washington and New Delhi, for example, have run training programmes for Afghan officials jointly with Beijing.

Why China and Russia might find common security ground in Afghanistan

But this also highlights the real failure of Chinese engagement in Afghanistan. Beijing has, sadly, not stepped in to take a more prominent and leadership role when it could have tried and clearly has all the links and tools in place to do so.

Beijing is ultimately going to be Afghanistan’s most powerful and influential neighbour. Pakistan may have deeper ties on the ground, but Islamabad is highly dependent on Beijing and likely to be even more so going forward.

Iran and Central Asia have also made large bets on Chinese economic partnership. China is now going to be seen as the major power across a wide swathe of the Eurasian heartland.

With all these connections, power and influence, China should logically have been a greater leader in Kabul. Admittedly, Afghanistan is a difficult country and China has little experience in conflict resolution of this sort, but it could have been hoped that it would have taken a more proactive role in a country with which it shares a border.

The Taliban won. Here’s what that could mean

There will doubtless be a certain amount of joy in Beijing as the narrative is advanced that Washington is leaving from China’s neighbourhood with its tail between its legs.

And Chinese officials will seek to play up the idea that this is the end of Pax Americana and a further demonstration of American fecklessness, something they will use in their larger narratives of confrontation with the US. But the US and the West were at least trying to bolster Afghanistan and help it transform.

Pre-eminent in Beijing’s concerns should have been the realisation that, while America may have played a role in making this mess, it is China that will have to live next to it at the end of the day.

Raffaello Pantucci is senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London