Pakistan hopes Joe Biden will maintain Donald Trump’s Afghanistan policy to preserve the Taliban peace process

- Afghanistan is Biden’s most immediate foreign policy challenge, with his range of options risking either the Taliban peace deal or decades of fragile progress

- Continuing Trump’s strategy would suit Pakistan as it would leave an ascendant role for the Taliban, a minimised Indian presence and a stable political order

With US President-elect Joe Biden due to be sworn in on January 20, Pakistani policymakers are watching the emerging contours of his Afghanistan policy which will shape the trajectory of US-Pakistan relations. A bipartisan consensus exists in Washington that there is no military solution to the war in Afghanistan and it should be terminated through a politically negotiated settlement, so a dramatic policy shift under Biden is unlikely.

A breakthrough in the intra-Afghan negotiations would augur well for US-Pakistan relations. The United States might restore suspended aid for Pakistan as compensation. However, a breakdown in peace talks and escalation of violence in Afghanistan would negatively affect bilateral ties.

Afghanistan is Biden’s most immediate foreign policy challenge, and his options range from bad to worse. If he maintains a counterterrorism footprint in Afghanistan, it would jeopardise the US-Taliban deal. The agreement necessitates, among other things, a full US withdrawal by May 2021 in return for Taliban commitments not to harbour foreign terrorist groups and to enter a power-sharing deal and comprehensive ceasefire with Kabul.

02:29

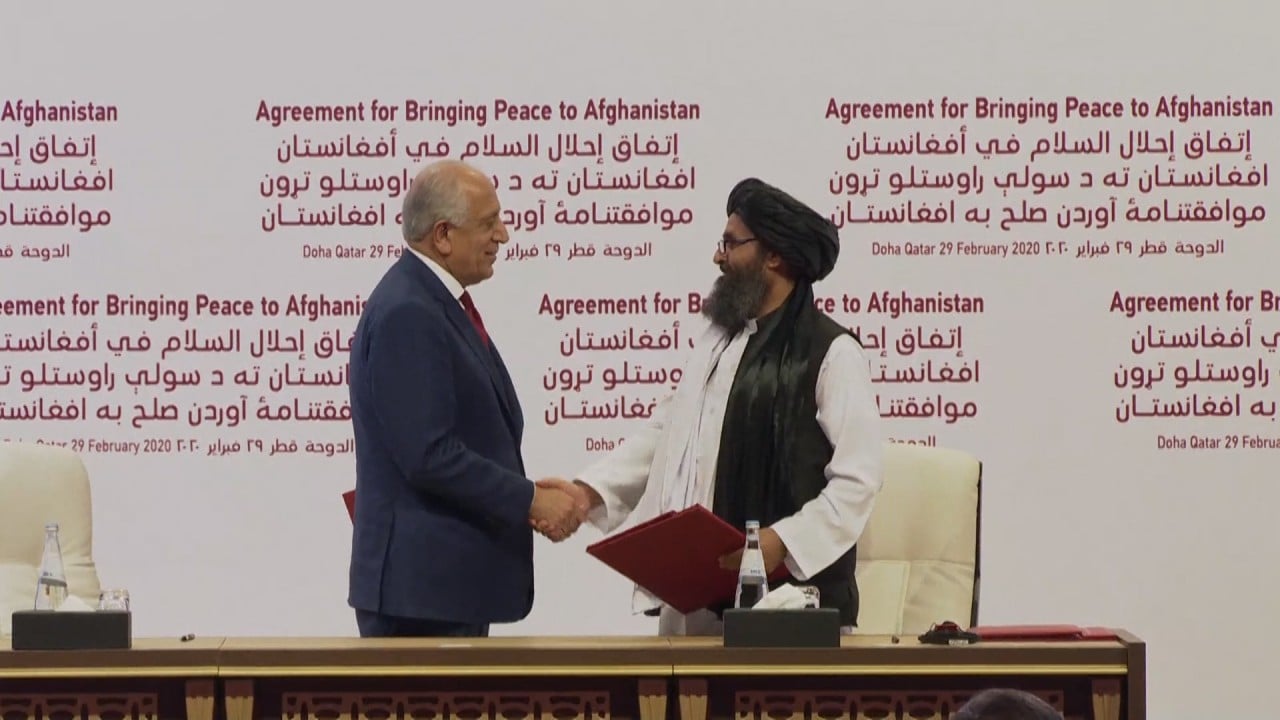

US, Taliban sign historic peace deal to end war in Afghanistan and withdraw US troops

From Washington’s perspective, a counterterrorism mandate targeted against al-Qaeda and Islamic State’s Khorasan province should have a buy-in with the Taliban leadership.

This is a likely source of Pakistan’s Afghan woes with the Biden administration. Islamabad would be expected to convince top Taliban leaders to agree to Biden’s new Afghan policy. However, that is easier said than done. If the Taliban agrees to a continued US presence in Afghanistan, it will compromise their ideological legitimacy and risk factionalisation.

The Taliban’s refusal to accept the US counterterrorism presence in Afghanistan will leave Pakistan in a Catch-22 situation. It needs to not give up on the former to secure its interests in Afghanistan, but it also needs to start on a good note with the Biden administration.

07:27

The Afghan peace process: trying to end the longest war in US history

Pakistan would welcome the Biden administration retaining Zalmay Khalilzad as the US special representative for Afghanistan, as the Pakistani military establishment enjoys a good working relationship with him. Since his appointment, Khalilzad has worked closely with Pakistani army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa. Their role was instrumental in clinching the US-Taliban deal and jump-starting Taliban-Kabul talks in Qatar.

The Biden camp is divided on keeping Khalilzad in his position. Given his knowledge of the Taliban, the Kabul administration and language expertise, some believe he should be retained until the transition is complete and Biden comes up with his Afghan policy.

Others want to see all those appointed by outgoing US President Donald Trump removed to start afresh. Further, they consider Khalilzad a controversial figure who signed a deal favouring the Taliban, not the US.

If the Taliban goes back on the February deal and the peace process breaks down, Washington will pressure Islamabad to use its influence to bring the Taliban back to the table or take action against its sanctuaries on its soil. Since 2009, the US Afghan policy has changed several times.

Why has Pakistan been left out of East Asia’s economic development boom?

This has strengthened the impression in Islamabad that Washington has not followed a consistent Afghan policy with clearly defined goals backed by requisite resources to achieve its goals. In this situation, Pakistan is determined not to allow the US to again use it as a scapegoat for American policy failures in Afghanistan.

Beyond Afghanistan, Pakistani policymakers believe Biden’s South Asia policy won’t differ from Trump’s, with deeper engagement with India and transactional, Afghan-focused dealings with Pakistan. Consistent with the policy of reviving America’s place as a global leader, instead of Trump’s isolationist “America first” approach, Biden could restore Washington’s position as a credible crisis mediator between India and Pakistan.

Abdul Basit is a research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Singapore. He tweets at @basitresearcher