Intellectual property theft: what Chinese and British firms should worry about

- Chinese companies are more vulnerable to data leaks through social media communications than foreign state-sponsored intellectual property theft

- Meanwhile, British companies should discard the belief that transparency buys trust

A British scientist, concealing his employment by a multinational trader, gained access to a processing plant in Fujian and obtained critical trade secrets. These profited his company and ultimately stimulated the British economy.

Tea manufacturing is convoluted: cultivation, picking, drying, heating, rolling, firing, sorting and packing, with specific methods for each stage. The process had been refined over centuries; outsiders could not discover it by experimentation. So the East India Company cheated.

Chinese commercial spying, by contrast, is generally aimed at intellectual property. It is driven less by nationalism than by commercial objectives, and is more commonly committed by Chinese companies against other Chinese companies than against foreign companies.

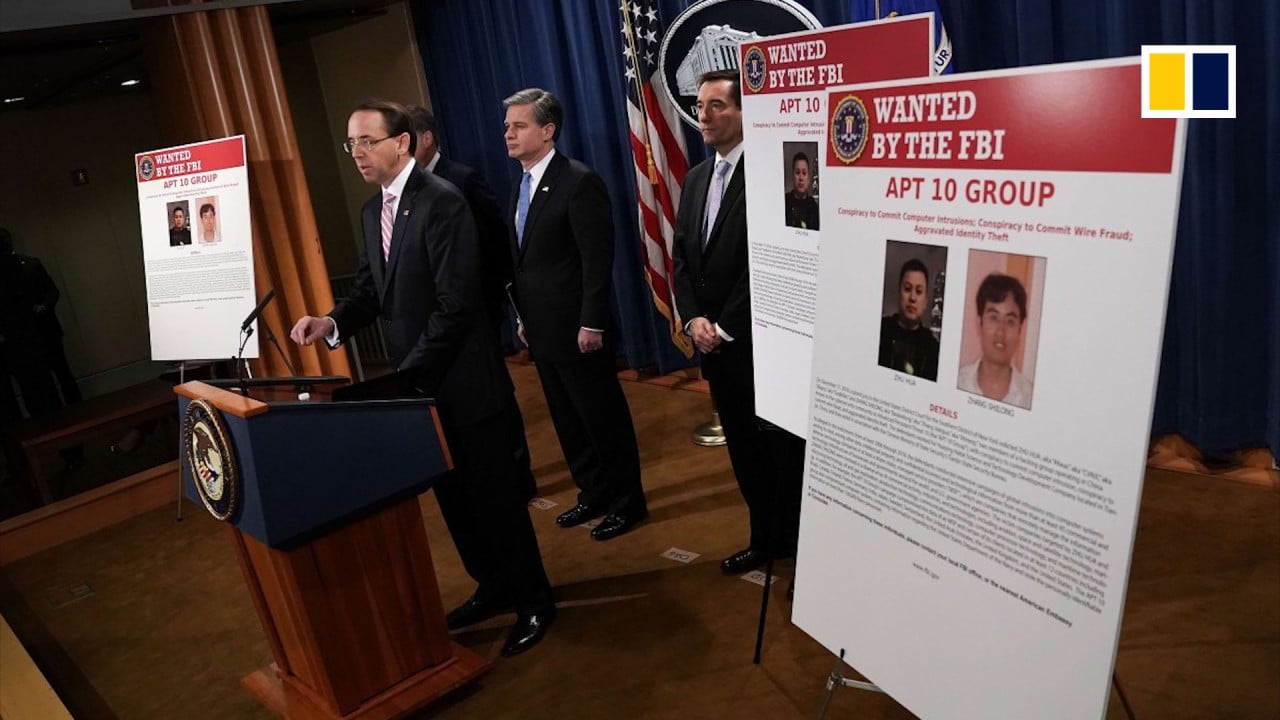

The cases that hit the headlines, however, are those where the Chinese government has actually taken part in the theft.

02:04

Two Chinese hackers charged as US accuses China of ‘massive hacking campaign’

Many Chinese businesses assume Western countries behave similarly. Recently one of our Chinese clients was presented with an information request by Britain’s Competition and Markets Authority during a national security review. Our client killed the deal rather than make disclosure, believing the United Kingdom was trying to steal secrets to help British companies compete.

This was not the case. While Britain’s Department of International Trade does help British companies export goods to China, there is no government department authorised to obtain and pass on commercial secrets to civilian recipients.

China’s government, on the other hand, does share commercial secrets of foreign companies with Chinese enterprises that might benefit, and in some cases facilitates the acquisition of those secrets.

China intellectual property cases surge as US complains of rampant theft

Chinese and British companies thus have different things to worry about in terms of commercial espionage. Chinese companies should concentrate on preventing leakage of information, which often happens via WeChat.

Senior management of that same Chinese company, however, having been fed a diet of distrust by state media, is likely to be feverishly protecting intellectual property assets rather than worrying about communications.

For example, a Shanghai-based newspaper urged Chinese food manufacturers to be wary of foreigners stealing their ancient recipes, an imaginary problem, and encouraged makers of jiaozi (dumplings) and tangyuan (sweet rice balls) to set up safeguards to stop this.

For British companies, the problem is a manic belief that transparency will buy trust. Only last week a colleague was asked to advise a UK technology company dealing with a Chinese supplier. She advised the client to perform due diligence on the supplier, but the company instead asked the Chinese entity directly for suggestions.

Chinese subsidies fuel surge in patents but experts warn of quality issue

The supplier gave the details of another company, suggesting that our client contact them for a reference. This would be like a detective conducting an investigation like this: “Excuse me, but are you the murderer?” “No, I am not.” “Sorry, my mistake.”

Due diligence is one area where Chinese and British companies have something in common: they’re bad at it. Businesspeople believe in their own perceptive powers – because they have served them well in their own country.

04:26

Chinese-American scientists fear US racial profiling

Sometimes their reluctance to do it stems from fear the investigation report will discourage shareholders from proceeding, but in reality the investigation seldom reveals a counterparty so dreadful that one should not work with it; more commonly, the investigator identifies risk areas and then produces a plan to reduce danger.

Trade war, IP theft the top risks for firms in China, Kroll report finds

Chinese and British business owners often see each other in black and white. Tremendous optimism becomes black despair when a deal doesn’t come off, and the counterparty’s entire nation is written off as either incompetent or dishonest or both, when in fact the problems arise from cultural differences.

It is these very differences that educate us, though, and businesspeople should deploy persistence and care to build profitable relationships.

Nicolas Groffman, who practised law in Beijing and Shanghai, is a partner at law firm Harrison Clark Rickerbys in London