Is the door closing for Beijing’s ‘wolf warriors’ on Twitter amid a US-China disinformation war?

- By fact-checking Donald Trump on other matters, Twitter has opened the door to a debate about who is posting what on its platform

- With millions of Americans sickened by Covid-19 and public opinion hardening against Beijing, Twitter may find itself facing a public backlash

The human and economic havoc wrought by Covid-19 has awakened Americans to a “war” many didn’t know the country was fighting, or didn’t care about – the US-China information war. It has been going on for decades. That Americans largely ignored it isn’t surprising. Most need bullets and bombs to think the United States is in a war.

When the virus first reached US shores, a reasonable expectation was that Beijing would be transparent about its origins, somehow make amends when Covid-19 was contained – even if it was just an apology – and take steps to ensure something like that didn’t happen again. The world would pull together and recover.

A few members of Congress began asking what Beijing was doing on Twitter in the first place; two asked Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey to remove Beijing’s “representatives” from the platform. Twitter replied in a tweet: “Official government accounts engaging in conversation about the origins of the virus … will be permitted” to stay on Twitter.

02:08

China says no evidence to suggest coronavirus virus came from Wuhan’s lab

As a private company, Twitter can largely do as it pleases. But with millions of Americans sickened by Covid-19 and public opinion hardening against Beijing, Twitter may find itself facing a public backlash – any social media company’s worst nightmare.

An analysis by Stanford’s Internet Observatory of this core showed they were mostly tweeting and amplifying on four topics, one of which was “Narratives around Covid-19 [that] primarily praise China’s response to the virus, and occasionally contrast China’s response against that of the US government”.

01:55

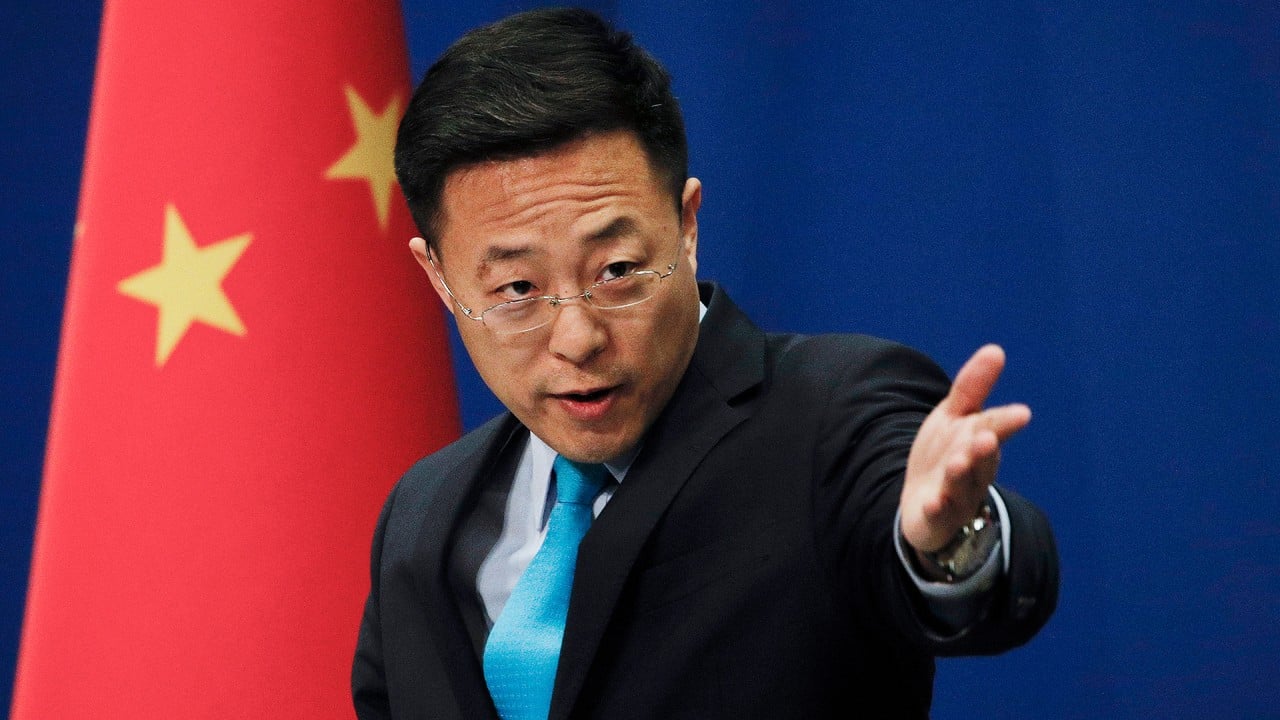

Chinese foreign ministry spokesman claims US army brought coronavirus to Wuhan

This narrative, pushed by these tens of thousands of accounts, also happens to be pushed consistently on the Twitter feeds of Beijing’s official spokespeople and news media. Since they seem the likely source for the parroted tweets of the networks Twitter took down, one might reasonably wonder if Twitter stopped short of fixing the root of the problem.

Let’s face it. A nobody keyboard warrior tweeting that the US army brought Covid-19 to Wuhan is hardly newsworthy. But Zhao tweeting it? That’s front-page news. His tweets, quickly ported to Weibo, were viewed more than 160 million times in the following 12 hours.

At press briefings and on social media, Beijing has continued to push the US army conspiracy narrative. On June 1, the Global Times thumbed its nose at Twitter, posting a slick video that further pushes the US-army-to-blame claim. It’s still there.

Warnings from inside over China’s ‘Wolf Warrior’ coronavirus diplomacy

By fact-checking Trump, Twitter opened the door to a debate about who is posting what on its platform. One might reasonably ask how Twitter can fact-check the president of the United States but not Chinese government spokespeople.

Twitter’s own rationale for shuttering the network of Beijing-linked accounts last August seems to have made the argument for the anti-Communist-Party crowd in Washington.

Even as their disinformation about Covid-19 continues, Beijing’s spokespeople have been tweeting incessantly to their millions of followers – taunting the US and specific leaders – about the racial protests there now. One could look at this and conclude that it’s a “coordinated state-backed operation” to “sow political discord”.

Robert Boxwell is director of the consultancy Opera Advisors