As Trump targets Iran, North Korea’s Kim would be wise to tone down his rhetoric and lie low

- When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, North Korea’s Kim Jong-il went into hiding, fearing he may end up being targeted like Saddam. As US-Iran tensions escalate now, it is worth wondering what lesson Kim Jong-un has drawn from that episode

In that earlier episode, North Korean officials bridled at their American counterparts who cited secret intelligence showing that Pyongyang was cheating by enriching uranium instead of reprocessing spent plutonium. There are two ways of producing fissile material for bombs, and uranium enrichment was barred under the 1994 Agreed Framework between the US and North Korea.

The result was a North Korean nuclear breakout and the situation that we are grappling with today, with Pyongyang having amassed a stockpile estimated at between 30 and 60 nuclear weapons.

The North Korean leader had probably backed himself into a corner in 2019, an unprecedented year of diplomacy which saw three meetings with his South Korean counterpart, President Moon Jae-in, suggesting that relations between the two Koreas would henceforth be conducted on a new plane.

In this regard, “a lasting and stable peace regime” would have been in the interests of both countries. For Pyongyang, this means that Washington must give serious consideration to partly or completely removing its regional nuclear deterrent. For Washington, the only basis for peace would be a meaningful North Korean denuclearisation.

This would suggest that, for whatever the reason, Kim’s goal is no longer denuclearisation. That’s if it ever was anything but the opposite: to keep the North Korean nuclear deterrent intact while bargaining for an arms control regime.

In short, the North Korean leader must reckon with the fact that the “imminent threat” criterion in international law (that is, the necessity for self-defence must be “instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation”, as formulated in the 19th century Caroline test) invoked by Trump remains relevant, even if unwarranted, as justification for US action against Soleimani.

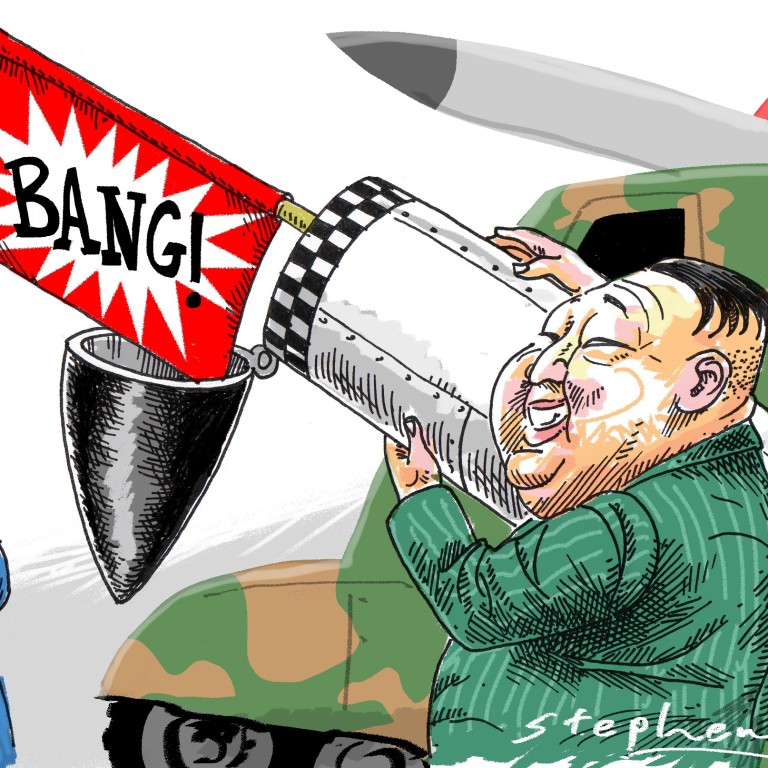

Thus, it could also be invoked to justify pre-emptive action such as a drone attack on North Korean missiles targeting US bases in South Korea or Japan.

To avoid returning to the days of fire and fury, Kim would be best advised to follow jazz maestro Duke Ellington’s advice to one of his lovers: “Do nothing till you hear from me”.

John Barry Kotch is a researcher and former US State Department consultant