Hong Kong’s retail landscape is changing as landlords lure restaurants to fill spaces abandoned by shops during pandemic

- The mix of tenants in malls and at street level is changing as restaurateurs pounce on slumping rents to expand

- Retail landlords are banking on them to boost footfall as people resume dining out amid an easing of Covid-19 restrictions

Gordon Lam, a caterer, had to endure a long wait to open his fifth restaurant, as Hong Kong’s tough Covid-19 measures barred evening diners.

But the wait was more than worth it for Lam and his business partners. They had managed to find their ideal premises after a leisurely six-month search of numerous vacant spaces, many of them offering cut-price rents and additional incentives.

What enabled them to find their perfect location at a favourable price was a trend that has emerged in Hong Kong’s retail property market in the last couple of years.

The space now occupied by SOW, measuring some 2,000 square feet, used to be an antiques shop.

Lam is paying a competitive price of less than HK$100,000 a month, and was granted a two-month rent free period by the landlord.

He said he came across some premises where the rent was a good 20 per cent below pre-pandemic market levels.

“Many [shops] have become restaurants. [Ours] could not be rented and was vacant,” added Lam. “We thought the rent was right so we rented it.”

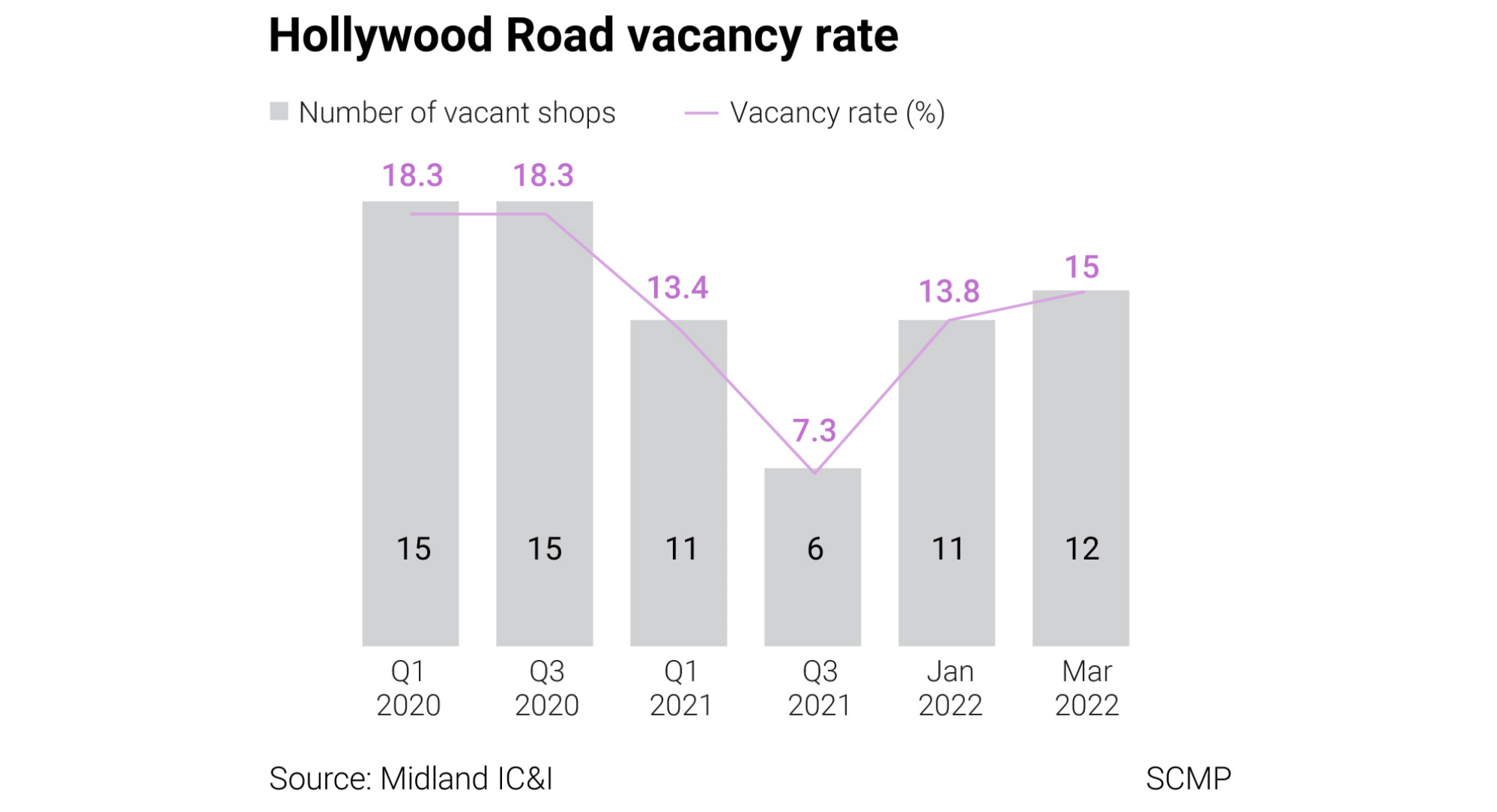

He said many of the famed antique shops in Lascar Row, in Sheung Wan, had been converted to restaurants after the pandemic all but killed off tourism in the city.

Lam spent some HK$4 million (US$510,000) to convert the premises for use as a food and beverage establishment, but considers it money well spent.

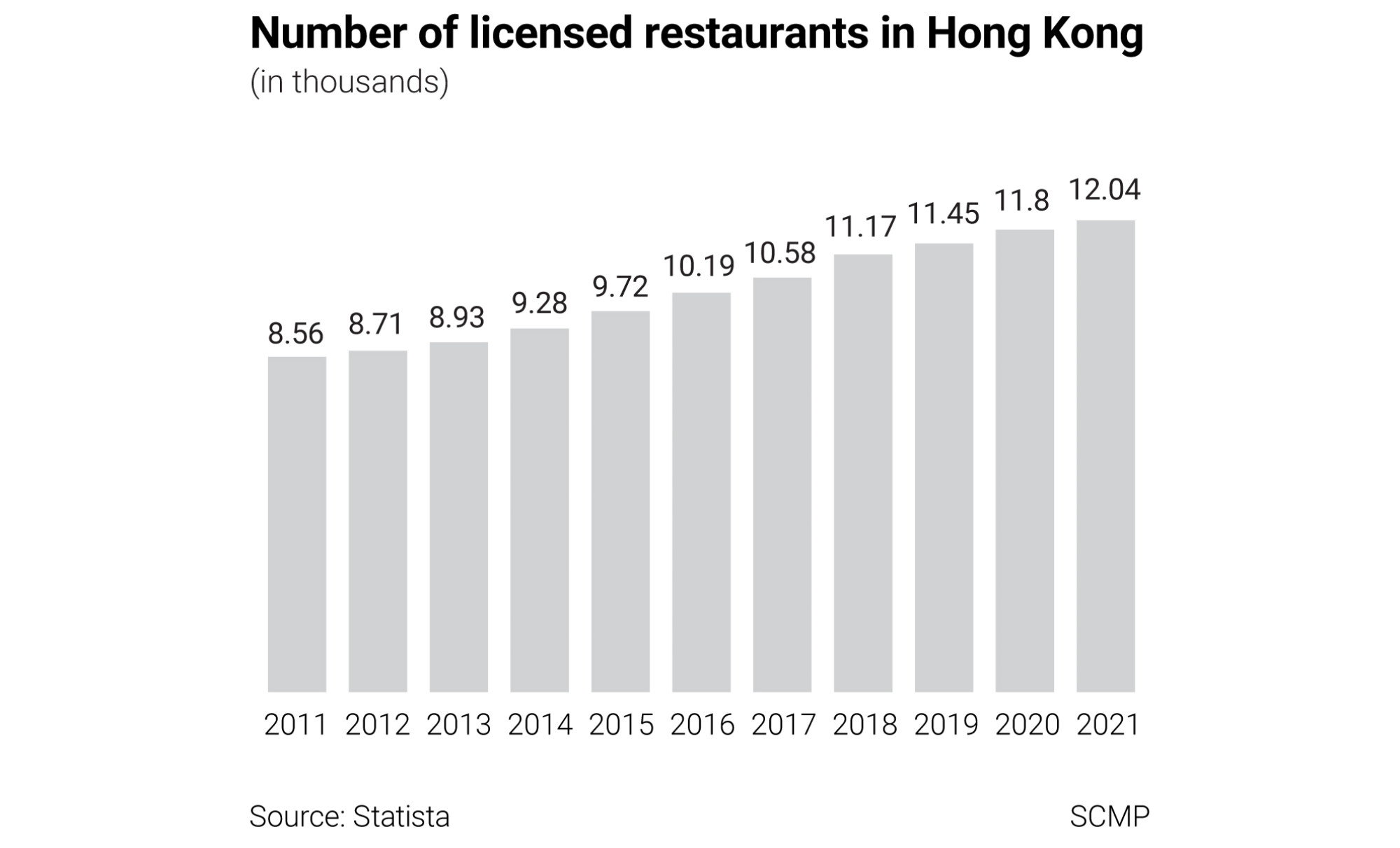

F&B used to account for around 20 to 25 per cent of the tenant mix in Hong Kong’s shopping malls. In some instances this is now up around 30 per cent, according to CBRE.

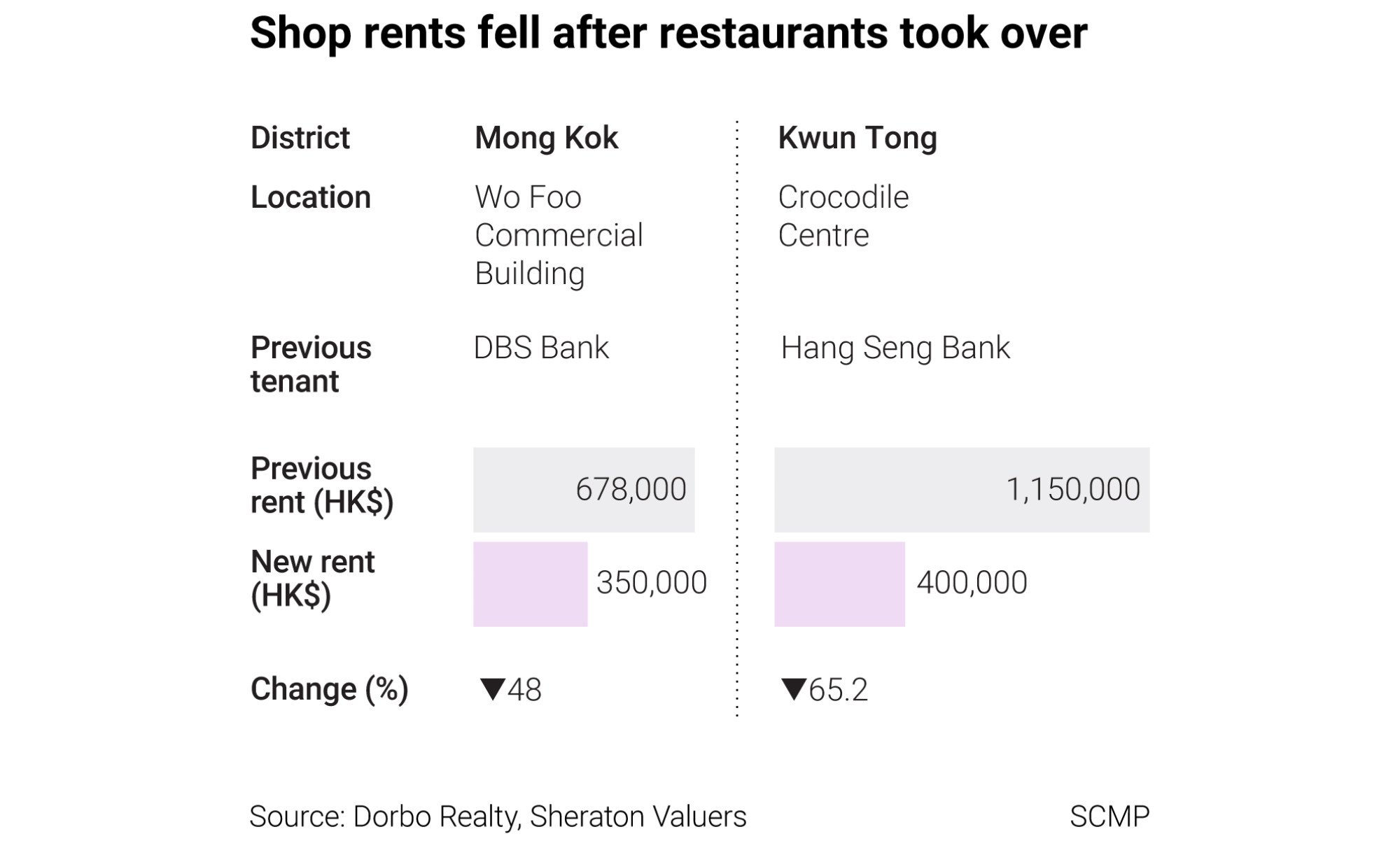

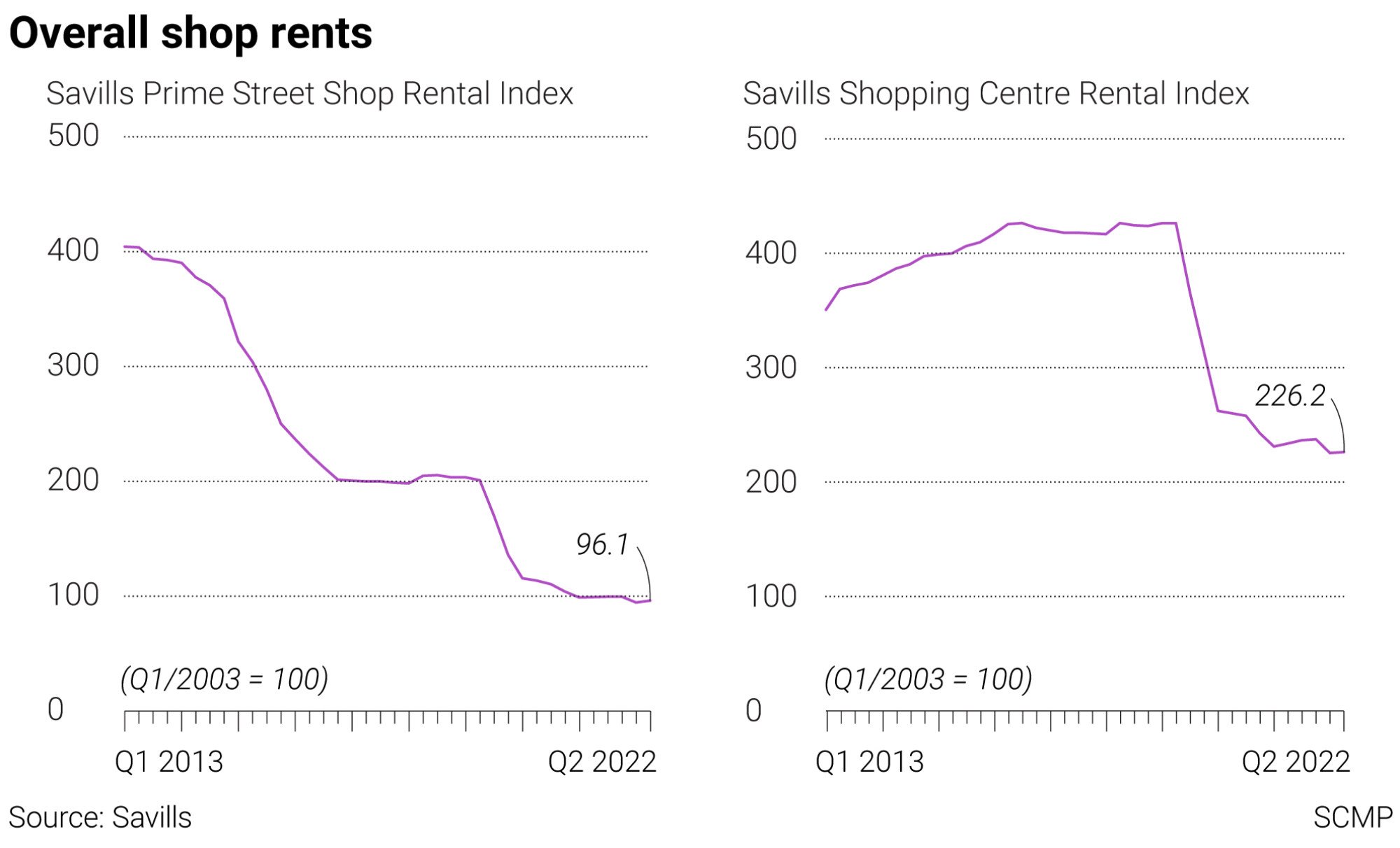

A high street shop rental index compiled by JLL is currently 75.3 per cent lower than the all-time high reached in the third quarter of 2014. That puts rents at a level last seen in the second quarter of 1988, the consultancy said.

Between April and June this year, about 160 restaurants opened on average every month, about half of them converted from retail to catering, said Chan.

The number of such conversions could rise to about 120 per month if the border with mainland China starts to reopen or social distancing restrictions are further relaxed.

And in June, the owners of Park Lane Shopper’s Boulevard on Nathan Road in Tsim Sha Tsui, one of Hong Kong’s four major tourist belts, submitted an application to turn the 300-metre long, 50-store complex into a food and beverage destination.

Founded in 2013, Hong Kong-based Pirata Group, which has 26 restaurants in Hong Kong, aims to have 100 eateries and a presence in five countries within the next five years. It plans to open at least 10 new restaurants next year and continue its international expansion.

“Disposable income in Hong Kong is very high at this point in time. So people are willing to go for experiences here in the city,” said Manuel Palacio, co-founder and chairman of the board at Pirata Group. “We’re looking very actively in the area. There are a lot of spaces and opportunities in Hong Kong right now. Terms are better.”

Many landlords are willing to commit to long-term leases, subsidise part of the cost by granting longer rent-free periods, and even on occasion help with the capital expenditure, said Palacio.

These arrangements can help foster “longer relationships”, and capital expenditure can be amortised over a longer period.

“Therefore, we can do better investments, and we can build better restaurants,” said Palacio.

Converting a former shop into a space suitable for F&B does not come cheap, however.

According to CBRE, the renovation cost is around HK$2,000 to HK$3,000 per square foot. There are many technical requirements, such as electricity and water supply, drainage and exhaust air extraction.

The conversion is handled by the tenants, not the owners of the premises.

In addition to front-of-house furnishings, a hefty investment is required into ventilation, refrigeration, cooking facilities and so on, said Steen Puggaard, the newly appointed CEO of Pirata Group.

“What we look for in F&B is a ratio that says every dollar spent on capital expenditure should yield at least three dollars. In annual revenue, this is a key metric we always look for,” he said. “Because with that, and assuming normal profit and loss and cost, we are able to get our investment back in three to four years. That’s an important number for us.”

As a rule of thumb, rental for retail outlets tends to be more expensive than for restaurants because landlords understand that the investment in capital expenditure for F&B can be substantially higher.

“F&B is probably four or five times as expensive as retail,” said Puggaard.

About 5 to 10 per cent of retail space will eventually be converted for food and drink use, according to Vincent Poon, chief operating officer at Tian Tian Catering Group, which has five restaurants in Hong Kong’s shopping centres.

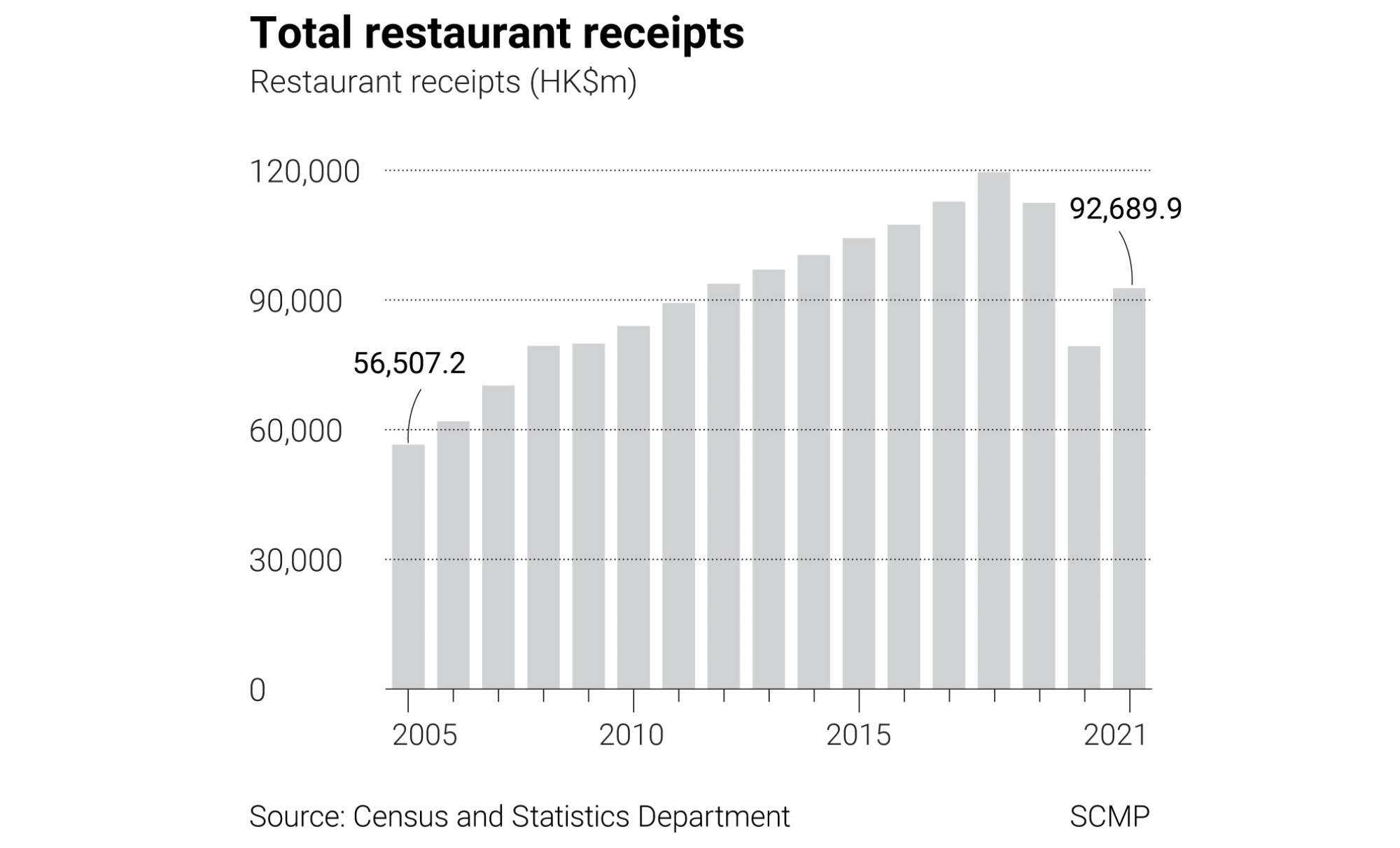

“Of course, the F&B market is recovering now. Retail, comparatively, is not recovering as strongly as F&B,” he said.

Poon’s company recently hosted a soft opening for Manner Dai Pai Dong, a restaurant offering food from Hong Kong and Macau in Shatin’s New Town Plaza measuring some 4,500 square feet.

“If rents come down, we’ll pick up the pace” when it comes to expanding, Poon said.

He said shopping centre rents had fallen after the Covid-19 outbreak, which had taken some of the pressure out of running a restaurant during such challenging times for the catering industry.

Nonetheless, he struck a cautious tone.

“If dine-in is suspended again, some F&B [operators] in Hong Kong will collapse,” said Poon. “If there is a sixth wave, about 10 per cent will shut down.”

Sales were most seriously damaged when dine-in services were not allowed in early 2021. In the event of a sixth wave of coronavirus leading to a re-imposition of such measures, his company would resort to takeaways.

“A lot of shops are turning to eating and drinking,” said Johnson Wong, director of Sky Big Group, which operates 19 Japanese restaurants in Hong Kong, with at least three more set to open soon.

Wong is prepared to open more restaurants when the locations are right and rents are cheap.

Many of his friends’ retail businesses suffered when rents remained high and footfall plummeted during the pandemic.

“The daily necessities can be sold in supermarkets. For street shops selling clothing, there is really not much business. How can they afford the rent?” Wong said. “Retail is really bad. Retail business is fragile.”

The spate of new restaurants is proving a big help for shopping mall landlords striving to boost footfall and sales.

“While landlords will likely try to convert retail space to F&B”, there will be fewer operators in the market just because their existing profit and loss model is not sustainable, particularly in conditions as difficult as those caused by Covid-19, said Puggaard. “Consolidation also creates opportunities.”

“F&B is very much a zero-sum game. Just because there are more options doesn’t mean people will increase the number of meals they have every single day.”

Space efficiency is important since “the less space we need for the same revenue, the better we’re monetising,” added Puggaard.

“Landlords need to strike a balance” between maximising the presence of high-yielding retail tenants with filling up vacant spaces with F&B and services, he said.