China’s battery makers burnish their safety image as they grab the lion’s share of the world’s market for powering electric cars

- CATL is now the world’s largest EV battery maker, with about 30 per cent of the global market, ahead of LG Energy’s 25 per cent, SNE Research said

- Chinese brands are fighting an uphill reputational battle against South Korean and Japanese brands, which have the image of being safer

The final instalment of a three-part series on electric car batteries looks at the quality and safety record of China-made packs, and how they stack up against competitors in South Korea and Japan.

How do EV batteries work, and why do they sometimes catch fire?

But before they could break the records, NIO and CATL had a more immediate task to tackle in 2019: how to assure cautious drivers switching to EVs for the first time that battery packs are safe. For buyers, many of whom count the family car as the largest big-ticket purchase of their lifetime after the home, the spectre of automobiles catching fire was a cause for pause.

“Nothing is more important than safety to a car driver,” said Phate Zhang, founder of the Shanghai-based EV news portal CNEVPost. “For consumers with the penchant for battery-powered vehicles, any news about cars catching fire will [douse] their buying interest.”

To be sure, NIO and CATL were not the first EV batteries to catch fire. That happened 10 months earlier in August 2018, when five incidents were reported in a month, mostly related to battery fires in EVs assembled by Lifan Motors in Chongqing and WM Motor in Beijing.

Still, the episodes raised questions whether the pace of China’s embrace of the EV was sustainable, especially in conjunction with the nation’s capacity to find a power source that is cheap, enduring and most of all, safe.

Top EV battery makers in the world

| Company |

Installation volume, Jan to Aug 2021 (GWh) |

Global market share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CATL | 49.1 |

30.3 |

| LG Energy Solution | 39.7 | 24.5 |

| Panasonic | 21.5 | 13.3 |

| BYD | 12.5 | 7.7 |

| SK | 8.8 | 5.4 |

| SDI | 7.9 | 4.9 |

| CALB | 4.6 | 2.9 |

| Guoxuan | 3.2 | 2 |

| AESC | 2.5 | 1.5 |

| PEVE | 1.7 | 1 |

| Others | 10.3 | 6.4 |

Source: SNE Research

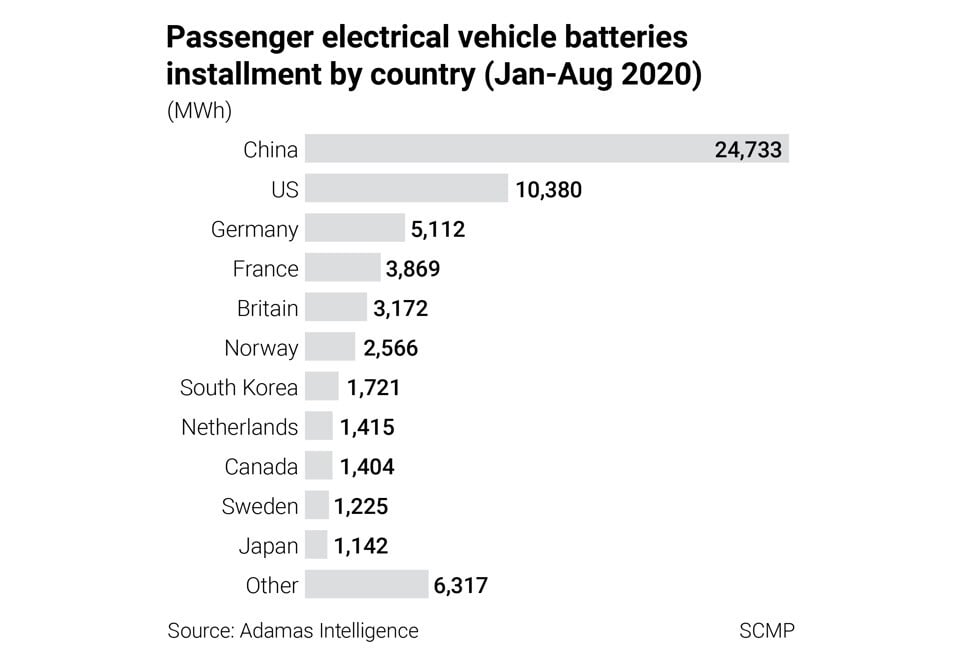

South Korea’s LG Energy Solutions began supplying EV battery packs to General Motors’ Volt plug-in hybrid car in 2009, before China-made products got into the global market. BYD mostly supplied its batteries to its namesake electric cars even if it began production in 2002, while CATL was only founded in 2011.

Chinese batteries, with less sophisticated designs than the packs made by LG Energy or Japan’s Panasonic, were shunned by global automotive marques because their weight and size made them unattractive for use. To make them lighter, Chinese companies had to reduce the number of cells, thus cutting the maximum driving range of a car.

“Batteries made by different companies may differ slightly in production quality and manufacturing defects, but the quality of a battery is more to do with what materials you use, and less to do with manufacturing quality,” said Wang Chao-Yang, co-director of the battery and energy storage technology centre at the Pennsylvania State University. “All those [battery] companies are so big, and their manufacturing and quality are all aligned with each other.”

Nearly all EVs on the roads globally use lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries, a type of rechargeable power pack where lithium ions move from the negative electrode (anode) through an electrolyte to the positive electrode (cathode) to discharge electricity. The battery, usually named after the cathode material, comprises four parts: cathode, anode, electrolyte and separator.

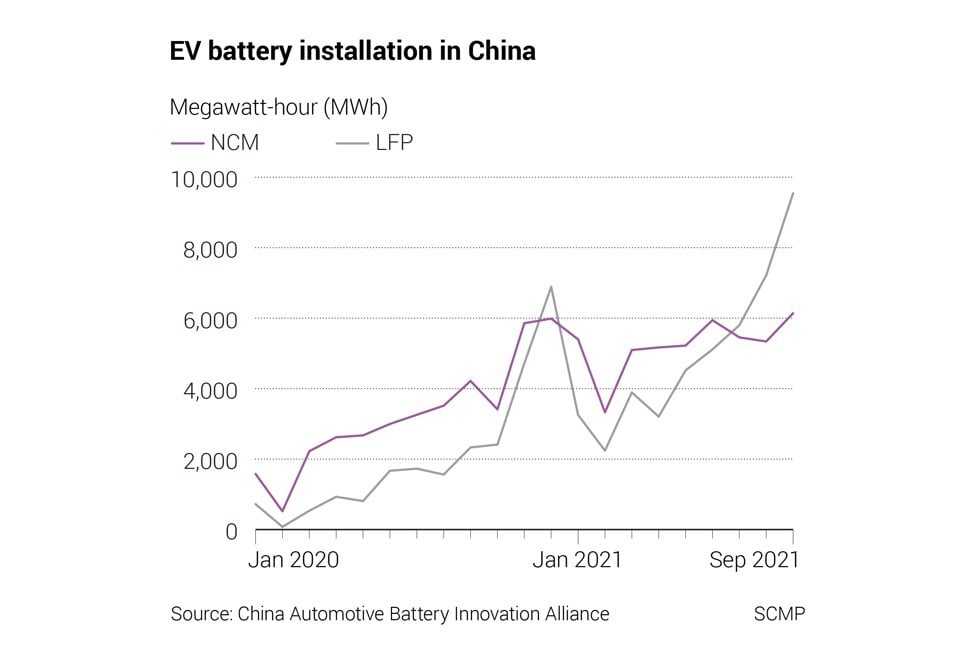

The three main variants of Li-ion batteries found in the bestselling EVs are the lithium-nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) packs, the lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries and the nickel-cobalt-aluminium (NCA) stacks.

The biggest drawback of Li-ion batteries is the liquid electrolyte used, which is volatile and flammable when operating at high temperatures. External forces such as a crash can also cause the chemical to leak, and catch fire. Flammable electrolytes are used in all NCM, LFP and NCA batteries, which means they can all catch fire.

Still, LFP batteries have better thermal stability, and are hence safer, with a lower chance of catching fire. The trade-off is that LFP packs are less dense, therefore can support shorter driving range before they need recharging.

“You have to be safe and stable first,” Wang said.

CATL produces NCM and LFP batteries. BYD, in which Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway owns 7.9 per cent, makes LFP packs, calling them “blade” batteries because of their long, thin shapes.

A module in the CATL battery pack used by NIO’s ES8 occasionally pressed up against a voltage sampling cable in the wiring harness, the carmaker said, citing its investigations. The contact could wear down those cables, which could lead to short circuits that could start fires, NIO said, before switching to a different battery pack design – still made by CATL – in late October.

Still, a month after NIO’s big recall in 2019, its delivery slumped to just 837 vehicles, making July the company’s third-worst sales month since the launch of the ES8 a year earlier.

NIO and CATL are hardly the only manufacturers saddled with battery fires. General Motors (GM) recalled 143,000 of its Chevrolet Bolt electric cars, representing most of the units sold since the model’s 2016 debut, after one of them caught fire while being parked at the owner’s home in the US state of Georgia on September 13.

A torn anode tab and folded separator within the battery modules were found to be the causes for the defects, GM said. LG Energy, which made the Bolt’s battery pack, agreed to pay US$1.9 billion to cover most of the cost for the recall.

“Battery safety is determined not just by the cells themselves,” said Davis Zhang, a senior executive at Suzhou Hazardtex, an energy solutions provider that supplies specialised vehicle batteries. “The design of the car, the battery management system and external factors can also play a role in [causing] fires. In NIO’s case, the accidents arose from faulty designs, not the batteries.”

The design of a battery pack depends on the performance targets that the vehicle wants to achieve, said Fitch Solutions’ associate automobiles analyst Phoebe O’Hara.

“If a car aims to offer a long cruising range on a single charge, an NCM or NCA battery offers the furthest range, the drawback being that they contain highly flammable cobalt and nickel,” she said. LFP cells, less flammable and cheaper, offer shorter driving range.

Last year, 82 cases of EV battery fires were reported in mainland China, according to the research firm GGII. In the first five months of 2021, the number of incidents more than doubled to 34, compared with the same period of last year, according to the research firm.

“The reported number of EV fires appears to be small,” said Chen Jinzhu, chief executive of Shanghai Mingliang Auto Service, which offers vehicle maintenance services. “Safety concerns about EVs and their batteries have been overdone. Most of the batteries are stable and secure enough, and the automotive industry is expecting new technology to improve the quality and safety of batteries.”

Tesla, the worldwide bellwether of electric cars, mounted a strong defence of battery safety in its

2020 Impact Report

, saying that there was a public misperception about electricity-powered vehicles.

“When the media reports a vehicle fire, it usually reports an EV fire. This is likely [to be] a result of the novelty of EV technology, rather than the prevalence of EV-related fires compared to ICE (internal combustion engine) vehicle-related fires,” Tesla said.

Petrol-guzzling vehicles catch fire at “a vastly higher rate” than electric cars, Tesla said, citing US transportation data that showed one petrol-powered vehicle fire for every 19 million miles travelled from 2012 to 2020, compared with one Tesla fire for every 205 million miles travelled.

SCMP Graphics: Electric vehicles and the Made in China 2025 industrial master plan

CATL, which also counts Tesla as a customer, is now the world’s largest EV battery maker, with about 30 per cent of the global market, ahead of LG Energy’s 25 per cent, according to SNE Research.

Still, Chinese brands are fighting an uphill reputational battle against South Korean and Japanese brands, which have the image of being safer because they have been in the industry longer.