Central needs upgrades to foster better connectivity for both people and cars, even as Admiralty takes over as leading hub

- The city’s historic business hub needs a new urban plan to improve pedestrian movement and connectivity, while also making road improvements to accommodate rising automobile ownership

- Hong Kong’s main business hub is shifting towards Admiralty as new infrastructure works are completed

During Hong Kong’s early colonial period, Central was the centre of the city’s administration. One of the lasting legacies of 150 years of British rule is that Central remains Hong Kong’s financial hub, containing not only the headquarters of all the city’s leading banks, but also its financial regulatory authorities – the Monetary Authority, the Securities and Futures Commission and the Hong Kong stock exchange.

But all cities change over time. Following completion of the Shatin-Central Link Phase II, by 2021, and the North Island Line by 2026, the Admiralty/Tamar area near Central will become Hong Kong’s largest metro hub and a much more prominent office node.

This increase in rail connectivity will be followed by the completion of a major new pedestrian footbridge and tunnel system linking new commercial buildings, like Hutchinson House, Murray Road Car Park, Queensway Plaza, Queensway Government Offices and the High Court Building, along with a new extension to the Pacific Place complex. This will inevitably mean that Admiralty and Tamar will share more of the central business district role presently enjoyed exclusively by Central.

All of this adds to the pressure on Central to reinvent itself – not merely as the city’s leading financial district, but also as an area which is more oriented towards leisure-based consumption.

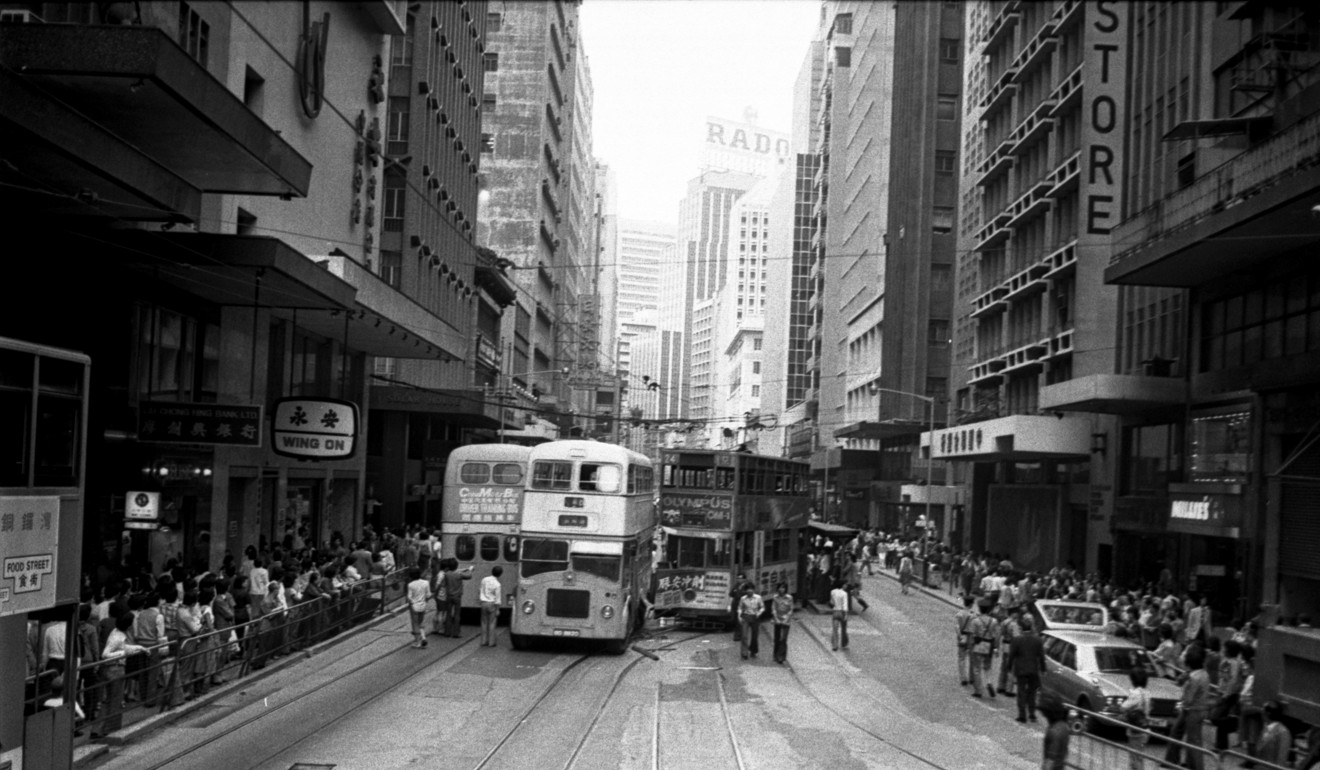

The revitalisation of Central is easier said than done. Firstly, Hong Kong is an enormously car-centric city. Automobile ownership has grown 40 per cent over the last decade, making for even greater automotive penetration of Central.

Secondly, Central’s layout makes it a very challenging area. Unlike many other cities, and some other districts in Hong Kong, Central is arranged in an irregular pattern of cramped and small streets, making it difficult for all types of people to walk around.

Thirdly, because Hong Kong remains one of Asia’s great tourist destinations, pinch points along main pedestrian thoroughfares in Central are growing worse, rather than improving. This is especially true after the recent opening of major new tourist attractions, such as Tai Kwun which, while drawing more people, have not been accompanied by traffic calming or pavement widening measures on Hollywood Road.

In 2012 the government established the Energizing Kowloon East Office (EKEO). Major developers have commented that, because it is backed by the government, the EKEO has been quite successful in encouraging major landlords and developers in the area to engage in constructive dialogue.

So, why stop with one fine urban planning experiment? Perhaps because no senior government official has stepped forward to shoulder the responsibility of applying the EKEO model to one of the most sensitive areas in Hong Kong. That means establishing an Energizing Central District (ECD), which would assume the demanding task of transforming the heart of the city’s financial district into a walkable, breathable, and enjoyable world-class destination.

Central needs a new plan that addresses the relationship between pedestrian movement, pedestrian connectivity, vehicle penetration and the volume of through traffic.

I’m talking about actions like removing street clutter, fixing holes and widening pavements to make them more walkable. Removing railings separating pedestrians from traffic, adding at-grade crossings where jaywalking puts people at risk, and implementing traffic calming and speed reduction measures.

Adding better and more streamlined wayfinding to connect Des Voeux Road Central and Queen’s Road to the harbour and neighbouring cultural sites, like Tai Kwun, PMQ and the Man Mo Temple would also be good. So would providing public amenities – shaded public seating, drinking fountains, greening and street art.

The overall objective should be to put pedestrian comfort, convenience and walkability at the centre of all proposals. Matters, such as improved traffic management, smart mobility, and an emphasis on public transport and congestion charging need to be seen as part of a wider objective.

To really be world-class, the Central waterfront needs to be easily accessible. Therefore, the development of Site 3 into a mixed-use cityscape – an open space where people have a chance to breathe and enjoy the harbourfront – is of the utmost importance.

To “reboot” Central’s identity, Site 3 must make full use of one of Hong Kong’s unique and precious assets – the harbourfront – and become a space for civic, cultural, leisure, entertainment and dining within a memorable landscape.

In short, major waterfront developments must be strongly iconic, much as the Opera House serves as a symbol of Sydney. They cannot be simply a cluster of office and retail properties.

Andrew Ness is senior consultant, strategic market intelligence at Colliers International (Hong Kong)