Dumplings, tai chi and a hint of racism: a Chinatown takes root in suburban Tokyo

Reactions to the sinicisation of an apartment complex reveal the complaints and complexities at the heart of Chinese immigration to Japan

There is a suburb with streets that reverberate with the Chinese language, and are saturated with restaurants serving authentic Chinese cuisine. But it might not be where you expect – this is the city of Kawaguchi, in the northern Greater Tokyo area.

At its heart is the Shibazono Danchi semi-public apartment complex, which is home to roughly 4,500 residents, more than half of whom are Chinese. It is regarded as the highest concentration of Chinese residents in all of Japan. Walking through the complex, almost everyone you encounter is Chinese, and precautionary notes in the language jostle for your attention. One reads: “Please don’t drink alcohol or shout near here. Urinating outdoors is prohibited.”

Jiang Qiguan has lived here since 2013, renting an old yet spacious flat for 80,000 yen (HK$5,640) a month. He was only asked to submit a few official documents before moving in, a much less complex process than other flats that require a guarantor and high surcharges. This convenience is the main reason Shibazono Danchi attracts so many first-generation Chinese immigrants. Typically, residents here are well educated, work in the information technology industry, and are twenty- or thirty-somethings with families.

China’s love-hate relationship with Japan is love again. Ahem

It is an ideal community for the 36-year-old systems engineer. Jiang speaks only elementary-level Japanese, so when he embarked on a lonely life away from his home province of Shangdong, he found it “heart-warming” to live somewhere cocooned in the sounds of his mother tongue. Frozen dumplings and his favourite doubanjiang (chilli-bean paste), available at a Chinese supermarket downstairs, provide a taste of his far-away home.

The Shibazono Danchi complex is just a seven-minute walk from the closest train station, allowing its residents to commute to Tokyo in less than an hour. Built in 1978, it is one of a number of public flats in suburban areas that the Japanese government established to cater to demand for low-cost rental units amid the post-war economic boom. Those who live in its eight residential buildings have access to amenities including a gym and a kindergarten.

“It used to have an elegant atmosphere”, said Yoshie Fukushima, 71. A widow, she won her home in a residential lottery run by the Japan Housing Corporation (now the Urban Renaissance Agency).

‘Pollution by tourism’: How Japan fell out of love with visitors from China and beyond

Fukushima has lived in the complex for 40 years. Her husband died many years ago; she is alone, but her story is hardly isolated. One Chinese resident said there was “no shadow of the Japanese” in the complex. “They stay at home as if they are in nursing homes,” she said.

Indeed, the complex’s original Japanese residents have aged, and some die alone in their flats – an occurrence so common in Japan that it has been dubbed kodokushi, or “solitary death”.

Younger Japanese prefer more modern flats downtown, freeing up space for Chinese immigrants to fill the empty rooms at Shibazono Danchi. Kiyomi Yamashita, a professor at Rissho University’s geography department, recently named the area “Nishi-Kawaguchi Chinatown”, noting its dense, lived-in feeling. “I was surprised when I conducted a survey. Even the fish and vegetable shops are run by the Chinese,” he said.

This is distinctive from Japan’s three large, traditional Chinatowns in Nagasaki, Kobe, and Yokohama, which are tourist spots for the Japanese. In fact, it is closer to the so-called Ikebukuro Chinatown in central Tokyo.

According to Yamashita, a wave of immigrants, mostly from Shanghai and Fuqing, arrived in the Ikebukuro Chinatown in the 1980s on the back of China’s opening up and a Japanese government campaign to attract 100,000 international students. More Chinese from the country’s northeast, including some with Korean backgrounds, followed suit in the 1990s.

He said new Chinese immigrants had settled in places such as Ikebukuro since there were Japanese language schools or part-time workplaces nearby, as well as cheap accommodation.

“These people have gradually settled in Japan. As they married and had children, they wanted a bigger home, yet could not afford to live in Tokyo. Therefore, they gradually moved to the suburbs,” Yamashita said.

Kawaguchi, where the Shibazono Danchi apartment complex is located, is not alone. An influx of Chinese residents into semi-public complexes has been observed in other suburban prefectures such as Chiba and Kanagawa. At the end of 2017, there were more than 730,000 Chinese residents in Japan.

When it comes to Japanese residents’ interaction with their new neighbours, frustration is a common theme. Fukushima, the widowed Shibazono Danchi resident, complains of Chinese children racing through the complex while their mothers are absorbed in their smartphones.

“The Japanese don’t act this way,” she said. Unable to discuss their concerns with neighbours due to the lack of a shared language, Japanese residents often resort to calling up local officials. Michihiro Kawano, a Kawaguchi city official, admits having received complaints pertaining to rubbish collection and noise pollution.

The “sinicisation” of the Shibazono Danchi complex has had some attention in the Japanese media. In 2010, the weekly magazine Shukan Shincho published a feature story titled “The Chinese complex that has 33 per cent Chinese residents”. Five years later, the right-wing magazine WiLL said the complex had been “occupied” by the Chinese, and expressed its concerns that this represented the future of Japan.

While Japanese-speaking Chinese find it easier to integrate into the community, those who have a limited command of the language find it challenging to make friends with Japanese locals. “What kind of [social networking services] do Japanese people use?” Jiang said, adding that he cannot “read between lines” when communicating with the Japanese.

Japan is open to foreign workers. Just don’t call them immigrants

Chinese residents said some homemakers were struggling to enhance their Japanese proficiency at home while their husbands were at work in Tokyo and their children were at school. Meanwhile, some Chinese grandparents are concerned about their grandchildren “turning Japanese”.

The Japanese government has so far failed to lay out much-needed social integration policies for foreigners. Still, the residents’ association at Shibazono Danchi is giving it a try. Association manager Hiroki Okazaki, 36, said the group succeeded in easing tension between Japanese and Chinese residents by requesting the complex’s management hire a Chinese staff member and distribute handbooks written in Chinese. “Visible problems have already decreased,” he said. This year, the association has received two awards for its endeavours towards integration.

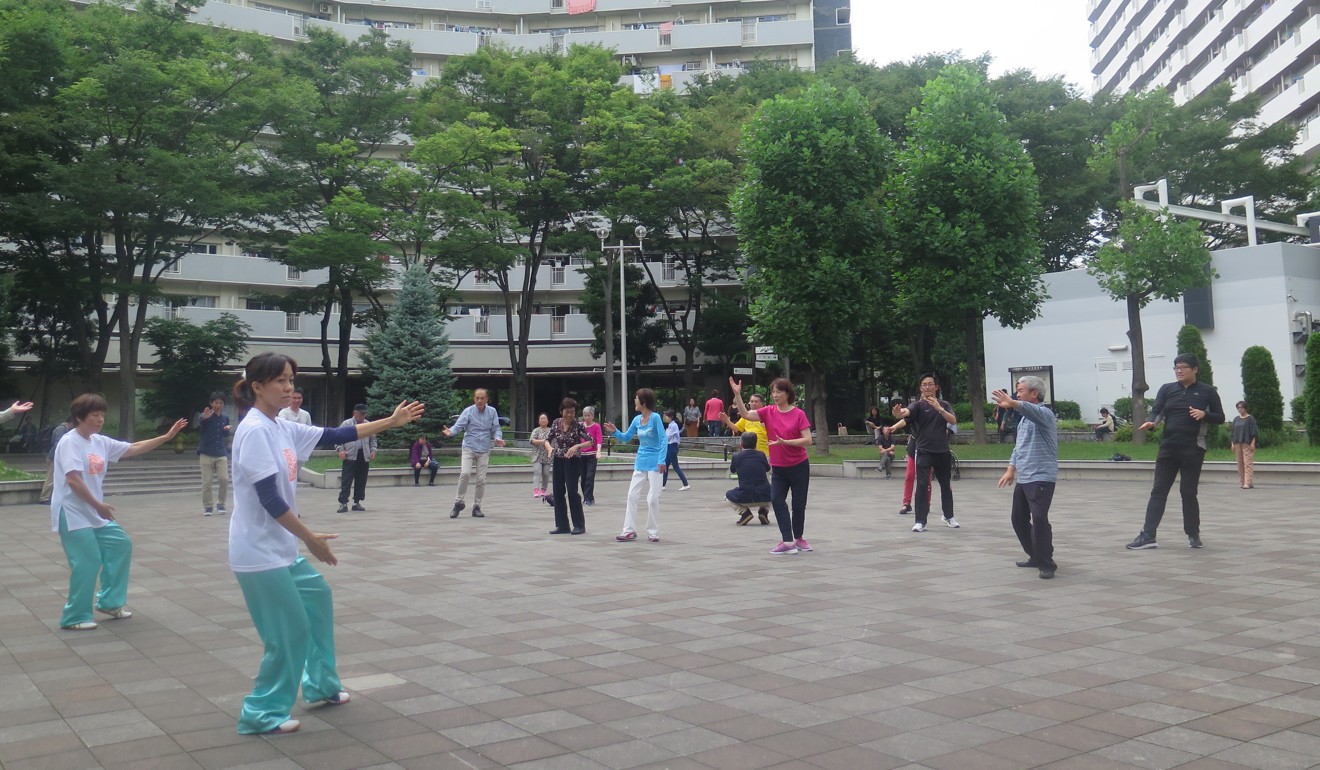

While some progress is being made, Okazaki believes a heart-to-heart between Japanese and Chinese residents is a long way off. Collaborating with Japanese student volunteers, the association regularly hosts cultural events such as Tai Chi lessons, flea markets and exchange gatherings – but the majority of the complex’s Chinese residents remain uncommitted and indifferent.

“Now I see that we don’t need to force the China-Japan friendship on both sides,” Okazaki said, “and that it’s good as long as we can set up a mechanism or environment where we can interact in a forward-looking way.”

However, there is a more amicable atmosphere near the Nishi-Kawaguchi railway station, where an array of Chinese restaurants provide authentic dishes such as duck neck and dao xiao (knife-cut) noodles.

“This area was once famous for sake, women, and dice,” said Ryoji Kokubo, a soba restaurant owner. At one point, the neighbourhood had more than 200 brothels competing to provide services at the cheapest rate, but police raids in the mid-2000s put an end to most such operations, and the Chinese restaurants moved in, catering to both Chinese and Japanese appetites.

Among them is Zamu zamu no Izumi, a restaurant that offers freshly hand-pulled Lanzhou noodles. “In Ikebukuro, the [turnover] rate is high, the rent is more expensive. We wouldn’t be able to focus on the taste,” one of the restaurant’s workers said. Its signature dish has gained an overwhelming response from locals, Japanese and Chinese alike.

Equally popular is Teng Ji Shu Shi Fang, which serves iron-pot steamed fish, a delicacy in northeast China. The owner runs several Chinese restaurants in Tokyo and has been rewarded for his efforts to appeal to Japanese taste buds. Thanks to the restaurant’s unexpected success, he has already decided to open a second outlet in the same neighbourhood.

With the spread of Japan’s suburban Chinatowns – and predictions by an expert at Rissho University that more overseas Chinese will move to Tokyo’s suburbs and high-rise condominiums as their social status rises – perhaps somewhere in these bustling eateries is a lesson in fusion that’s worth digesting. ■