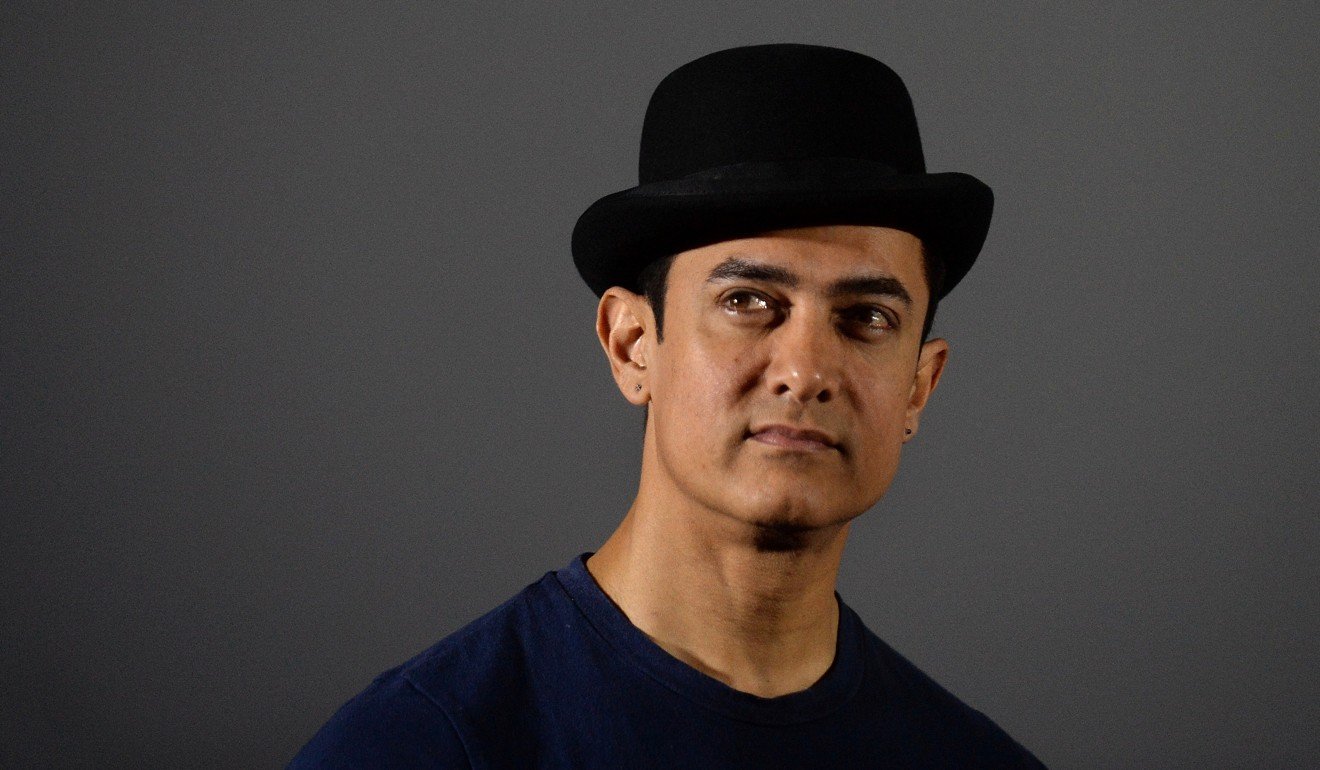

Meet the Secret Superstar of China, from India: Aamir Khan

Bollywood actor Aamir Khan is shattering box office records left, right and centre. But can he transform his place in the hearts of everyday Chinese into a bridge between nations?

He is the movie star with many names. “India’s conscience” to Chinese media; “Guaranteed Sales” to film distributors, and nothing less than Nan Shen (Male God) to Mandarin-speaking silver screen lovers. Yet those most familiar with the man shattering record books for Bollywood films in China refer simply – and fondly – to “Uncle Aamir”.

The current excitement surrounds Khan’s latest movie, Secret Superstar, a 150-minute film that has become one of the most profitable films ever (it cost only US$2.4 million to produce but is expected to gross more than US$98 million in China alone). Indeed, the more than US$46 million it took in the first seven days since its China release last Friday was a record for an Indian movie in China, eclipsing even Hollywood hits such as James Cameron’s 2010 mega-hit Avatar.

WATCH: Secret Superstar trailer

The movie, a coming-of-age story about a Muslim teenage girl who dreams of fame as a singer and finds it after uploading a YouTube video, has struck a chord with Chinese audiences who see many of India’s social issues – the film tackles gender inequality and domestic violence, among others – reflected in their own experiences. The film – rated eight out of 10 on Douban, a viewer-led movie-ranking website similar to IMDb – has dominated discussions on Sina Weibo, China’s answer to Facebook, for days. Even Chinese state-run media has weighed in, with the online version of People’s Daily praising it for “touching the soul”.

Pakistan’s forbidden romance with Bollywood

The film’s runaway success is further proof of Khan’s knack for pulling at China’s heartstrings. Secret Superstar is the latest in a string of recent hits that included 2009’s 3 Idiots, another coming-of-age comedy drama that resonated with Chinese audiences, this time for its probing of the dark side of the Indian education system and the role of parental pressure in student suicides. Khan’s first foray into the China market was Lagaan in 2003, which told the story of Indian villagers learning an alien game (cricket) and playing against British colonists for a result that would change their village’s destiny.

Yet while Khan’s box office appeal can be seen in black and white, there is an enigma surrounding his growing following in China. In succeeding where many of India’s finest actors have failed in the past, he has given rise to hopes not only that Bollywood has finally cracked the secret of the world’s second-largest movie market, but that India’s image may be softening in the eyes of its great Asian rival. That the connection Chinese audiences feel to Khan may show love is finally gaining the upper hand in the love-hate relationship between the two nuclear-armed, rising superpowers who as recently as last year were locked in a military stand-off over a disputed border.

WATCH: Aamir Khan in Chengdu

And if international peacemaker sounds like one of the more improbable roles Khan has auditioned for, it’s a part he would be happy playing. The actor, currently touring China with co-star Zaira Wasim, told fans this week he wanted to help “improve India-China ties”, according to the Press Trust of India. “I want to do a film with Chinese and Indian talent,” he said. “It would be really wonderful … It would bring the two countries closer.”

In recent years, Chinese and Indian leaders have encouraged their filmmakers to act as cultural ambassadors. Beijing and New Delhi inked an agreement in 2014 testing the water for film co-productions. But their best known production, Kung Fu Yoga, an Indiana Jones-style adventure film starring Jackie Chan from Hong Kong and Disha Patani from Bareilly, was panned by critics. Despite impressing at the box office – it grossed US$254 million worldwide – Kung Fu Yoga was rated as low as 5.3 on IMDb, and received an ever lower rating – 5 out 10 – on Douban.

WRESTLING WITH SUCCESS

Khan’s place in Chinese hearts and minds may have been growing since Lagaan, but it was the release of Dangal , the true story of a wrestler’s quest to train his daughters as world-class fighters, that sent him into the stratosphere. The movie was voted best foreign film in 2017 on Douban, beating out competition from Hollywood Oscar winner La La Land and British Academy Award nomination Darkest Hour.

When it took the Chinese box office by storm last year it became only the second Indian movie over the past decade (apart from another Khan film, the 2014 fantasy flick PK) to have grossed more than 100 million yuan (US$15 million).

WATCH: Chinese fans pay tribute to Dangal

Inevitably, Khan’s string of successes has given rise to speculation that Bollywood has finally cracked the Chinese market. “[Before Khan], Chinese audiences were not that into Indian movies,” said Wu Lixiang, who runs Beijing-based website Entertainment Capital.

According to most critics, the major roadblock to crossover success for Bollywood films is the tendency of dancing scenes to break out in the middle of the storytelling. But as Khan’s fan base grows, viewers tastes are changing.

“My friends and I had rarely watched any Indian movies until Uncle Aamir’s performance caught our eyes,” said Meng Jiarong, 24, a business school student in Hangzhou, near Shanghai. “In the past, even if we came across Indian movies on television, we would quickly switch the channel as we could not connect with the Bollywood dancing,” Meng said. “But now, perhaps because we love Uncle Aamir so much, we find ourselves enjoying the dancing, too. It is really not that bad.”

Industry analysts say such changing attitudes could help Bollywood grab a greater slice of a multibillion-dollar market. In 2016, China’s box office takings surpassed US$8 billion, according to global consultancy PwC, which forecast the Chinese movie market would overtake the US to become the world’s biggest, possibly by as soon as 2021 (a prediction based on compound annual growth of 11 per cent).

WATCH: Dangal, official trailer

Wu, of Entertainment Capital, said the success of Uncle Aamir in China had played a key role in sparking that interest. While filmmakers worldwide were competing for China’s attention, “many Chinese film distribution companies are paying closer attention to Bollywood”, Wu said.

“For most people in China, they have never heard of the Khans of Bollywood,” he explained, using a term that usually refers to Shah Rukh Khan and Salman Khan in addition to Aamir.

“We Chinese only know Uncle Aamir.”

KHAN YOU FEEL THE LOVE TONIGHT

In fact, Khan’s influence now stretches far beyond China’s cinema screens. His biography I’ll do it my way can be found at bookstores across the nation, while his television talk show Satyamev Jayate has been translated into Mandarin and is widely available on Chinese streaming platforms. Even Chinese online retailers are cashing in, selling everything from Uncle Aamir smartphone cases to black hats like the one he wore in Dhoom 3.

There are myriad reasons ordinary Chinese give for falling in love with the 52-year-old from Mumbai.

Among the most common, at least on the Chinese Q and A internet site Zhihu (which has more than 240 questions under Khan’s name), is that he is “handsome”, “a good performer” and “committed to his work”.

Stories of how the actor gained 25kg to shoot some of the scenes in Dangal (then shed them within half a year to complete filming) have entered social media folklore in China, while the tendency of his films to tackle difficult social issues has also won fans over.

WATCH: The making of the Dhaakad girls

“He has a pure heart,” said one poster on Zhihu. “Every movie he has acted in points to an issue of India. He knows his country’s problems well … and he wants to make a difference through his work.”

And it’s not lost him any points that he hasn’t been shy of criticising his home country. In one notorious incident in 2012, Khan used his talk show to open fire on India for failing to tackle social ills including sexual abuse, arranged marriage and caste discrimination.

It was flashes of social conscientiousness like this that earned him not only a spot on Time magazine’s 2013 list of the world’s 100 most influential people, but a spell as a Unicef goodwill ambassador for South Asia and a place in the heart of ordinary Chinese.

“Aamir Khan is God’s gift to India,” the Zhihu user wrote. “We can’t help but love him.”

The question is: how long can that love last?

CAN LOVE BUILD A BRIDGE?

The same political dynamic that make Khan’s popularity in China so noteworthy could work against him if relations between the two Asian powers deteriorate – as they frequently threaten to.

The countries have a love-hate relationship that dates back at least to the Sino-Indian Border Conflict of 1962. Since then, ties have been punctuated by economic competition and border disputes, even if there have been notable bright spots too – India was among the first countries to end formal ties with Taipei and recognise Beijing as the legitimate government of China.

The latest reminder of the tensions came early last year, when Indian troops and their Chinese counterparts were involved in a months-long stand-off at the India-Bhutan-China tri-junction that raised fears the countries were heading for a second war.

The border dispute has cooled somewhat, but analysts say the shadow it has cast on Sino-Indian relations still looms large. Competition between the countries clearly remains, and is exacerbated by America’s seeming keenness to court India as a way of curbing China’s rise – a motive analysts detected in US President Donald Trump’s recent decision to relabel the Asia-Pacific region as the “Indo-Pacific”.

Border stand-off with India be damned, Chinese love for this Bollywood film just keeps growing

Khan’s recent successes have appeared immune to such long-simmering disputes, however. Even as the Doklam border disputes stirred up anti-India sentiment on Chinese social media last year, Dangal’s popularity continued to soar, with its rating on Douban growing from 8.8 out of 10 in May to 9.1 in July.

Likewise, his success flies in the face of polls. The Global Times reported in December that Chinese felt India was the least friendly country towards them (other than Australia, which had recently been critical of Beijing’s attempts to influence its domestic politics) and that the feeling was mutual among Indians. A 2017 survey by the Pew Research Centre showed that just 26 per cent of the Indian public held a positive view of Beijing.

Yet none of this stopped moviegoers across China from cheering when Geeta Phogat, the female wrestler in Dangal played by Fatima Sana Shaikh, wins gold and the Indian flag is raised to the tune of Jana Gana Mana, the Indian national anthem.

Even so, Stanley Rosen, a political-science professor at the University of Southern California, doubted Khan’s influence could survive any further souring of China-India relations. “If the border dispute heats up, the Chinese government will not approve any Indian films for China,” Rosen said. “Politics will always come first, and the import of films is a carrot China is offering to India. Aamir Khan’s popularity is useful for both countries, but it cannot override the larger issues in the relationship.”

Rajinikanth: The Tamil star who has a cult following in … Japan

Liew Kai Khiun, a soft power expert at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, questioned whether a handful of successful Bollywood movies signalled a new trend in Chinese soil. “These films do not represent the rise of Indian popular entertainment in China,” Liew said. “Their box office hits are largely isolated in nature, and compared to Korean and Japanese influences [in China], one does not see more sustained popularisation of Indian fashion, food, tourism and popular songs and television drama for Chinese consumers.”

WATCH: Chinese speaking Hindi dialogues from Dangal

The growing legion of Uncle Aamir fans beg to differ.

“With Uncle Aamir gaining popularity in China, I do believe Chinese people are now willing to learn more about India,” said Eric Liu, 23, a human resources professional in Shenzhen.

“Thanks to Uncle Aamir, I now know that India not only has curry and poverty, but also has many Indians who are ambitious, persistent, hard working and keen to make a change, just like those in 3 Idiots,” Liu said. “I think they deserve our respect.”

And while not everyone would agree with him, even for many Chinese who admit to disliking India, hostility is no longer 100 per cent.

“Generally speaking, I do not have a good impression about India because of the Doklam stand-offs,” said Stray Mao, an insurance salesman in Hangzhou.

“But I do like Aamir Khan’s movies and I admire him very much. He is such a great actor. So talented and committed. His movies make you laugh and also make you cry. I find them inspiring and full of positive energy.”

Mao, 24, has watched Secret Superstar and is encouraging his friends to do the same. “It’s so good. I don’t mind watching it again,” he said.

Like many others, he has learned to compartmentalise any conflicts between his views of Indian geopolitics and the (increasingly) familiar face of Uncle Aamir. “For me, politics is politics,” he said. “Movies are movies.” ■