The Australian authors proving a hit in China

From Thomas Keneally of Schindler’s Ark to John Marsden of Tomorrow When the War Began, writers are helping to boost exports from Down Under

Australia sends a lot of things to China: iron ore, lithium, wine, meat. And now, China is also the country’s biggest market for books, with more contracts for Australian-penned stories signed with publishers in China than in either the United States or Britain.

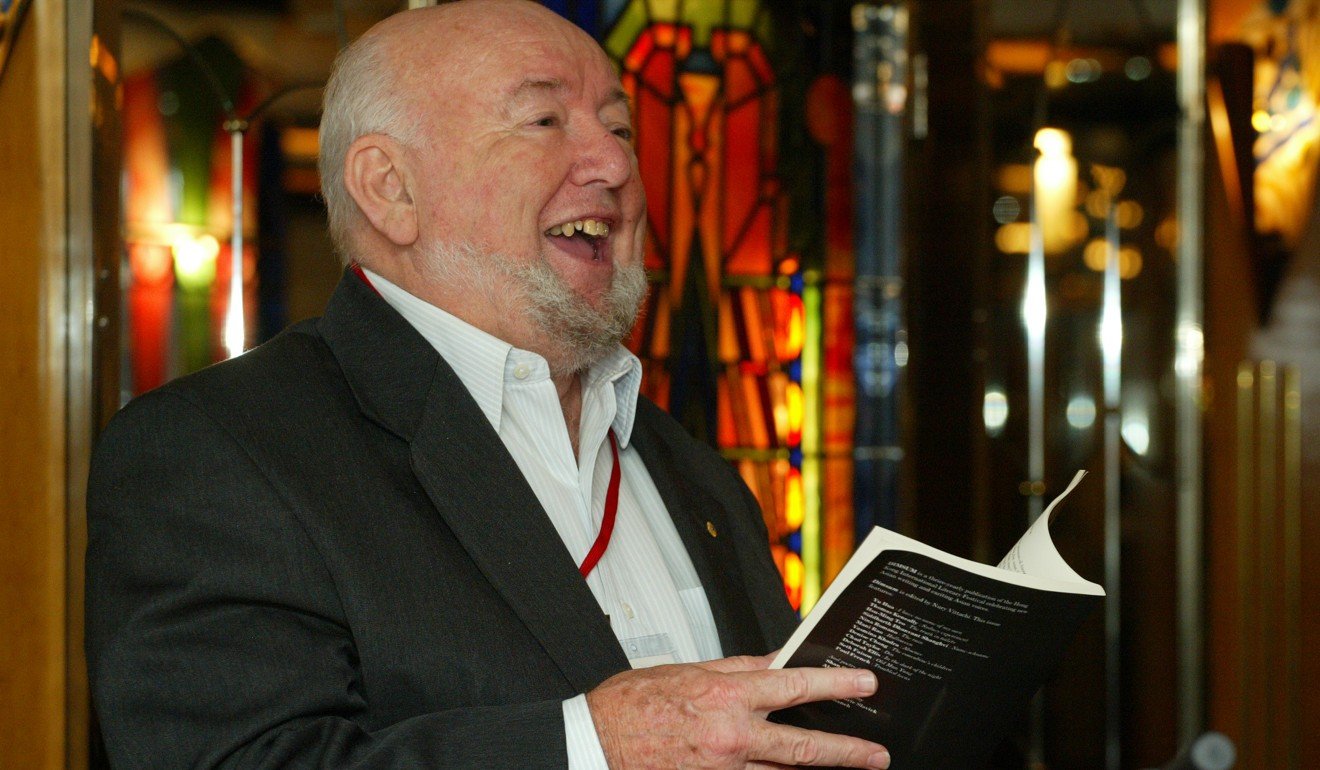

Australian Writers’ Week in China has just finished up. This was its tenth year and some of Australia’s heaviest-hitting authors were there to celebrate: Thomas Keneally, author of Schindler’s Ark (which was made into the film Schindler’s List), Geraldine Brooks and teen author John Marsden, best known for his Tomorrow When the War Began teen series about a group of young people fighting foreign invaders in Australia.

Tree clearing may have killed 180 koalas in Australia in just two years

But according to The Sydney Morning Herald, the real show-stopper was Aboriginal children’s author Bronwyn Bancroft, who ended up in tears after a reading at a primary school where the children burst into applause. The event visited eight cities: Beijing, Shanghai, Harbin, Xian, Chengdu, Suzhou, Hohhot and Guangzhou.

Australian ambassador Jan Adams said: “Over the past decade Australian Writers’ Week in China has seen many of Australia’s most exciting authors travel to China, to share their stories with Chinese audiences and celebrate contemporary Australian writing”.

They have included poet Les Murray, Kate Grenville and Tim Flannery.

In the 13 years to 2015 some 3,200 Australian titles were translated into Chinese. From 1981 to 1988 that figure was 15.

Chinese people are increasingly interested in Australia, with 33 Australian studies centres across the country, according to the Australian embassy in Beijing. Much of the translation work has come out of these, such as the Australian Studies Centre at the Shanghai Institute of Foreign Trade, which ran a programme to translate ten Australian books in 2010.

Jo Lusby was managing director of Penguin Random House for north Asia. She said: “The Australian government has invested time and money in supporting and promoting Australian literature in China – around 15 years of consistent activity such as supporting translations, taking authors over, and facilitating exchanges.” But she also noted that there was a general boom in both foreign books and children’s books in China.

Proportionally those 3,200 books over 15 years is not much, compared with overall figures. According to China Publisher’s Yearbook in 2015 the country bought the rights to 15,542 books, more than a quarter of them from the United States.

In contrast, China published only 404 Australian titles. But considering Australia’s small population of only 23 million it is a reasonable effort.

Australian police consider charging Vatican finance chief George Pell over abuse claims

However Eric Abrahamsen, a Chinese book and publishing expert at Paper Republic, thinks name recognition for Aussie authors is lagging. “Australian authors aren’t very well known in China. I’d say the only novel that had a chance of recognition is Schindler’s Ark, and only there because of the movie.”

Keneally’s book has sold 40,000 copies in China according to a story from The Sydney Morning Herald.

Children’s books are also doing particularly well, thanks to there being 370 million children in China and a growing focus on reading for pleasure. Apparently the top seller is The Magic School Bus, but as elsewhere Peppa Pig books also do very well.

A paper put out by the Australian government said that as the mining boom slows, establishing cultural connections and “linked cultural projects” is important and “crucial for lasting ties between countries”.

Two men who have been crucial to lasting literary ties between the nations are Li Yao and Professor Huang Yuanshen, who have both translated many Australian titles. The former graduated from Sydney University and translated more than 30 Australian titles over almost 40 years and was honoured last year by the Australian embassy.

At a time when misunderstandings between China and Australia can be common, most recently at the blood diamond conference in Perth, better cultural understanding will help. Meanwhile as more Chinese students continue to flood Australia’s universities a greater interest in its books could be likely.