Indonesian stars Via Vallen and Didi Kempot are keeping Javanese alive in pop culture

- Javanese isn’t the national language but it’s very much alive in music and in politics, with all seven Indonesian presidents, including the late Sulawesi-born BJ Habibie having Javanese heritage

- Bahasa Indonesia became the national language to unite the country’s numerous ethnicities

Moreover, Javanese is very much alive, both in popular culture and politics. For example, one of Indonesia’s most famous pop stars Via Vallen, has attracted more than 186 million YouTube views for her song Sayang, (Love). She was also chosen to sing Meraih Bintang (Reach for the Stars) at the 2018 Asian Games in Jakarta.

Another singer, Didi Kempot, known as the “Godfather of Broken Hearts, is a quintessential old-school Javanese troubadour but even at 52 has developed a huge millennial fan base.

Jokowi’s Javanese power play has Prabowo in face-off with an old army nemesis

But how did this happen? How did Javanese, the language of Indonesia’s largest ethnic group, stop short of becoming the national language?

Indonesia’s national awakening – and its struggle for independence – took root with the Youth Congress of October 1928 when nationalist youth leaders from across what was the Dutch East Indies converged on Jakarta.

The main outcome of the meeting was the so-called Sumpah Pemuda (Youth Pledge), which committed Indonesia’s nationalists to fight for one motherland and one people while acknowledging one national language: Bahasa Indonesia.

The attendees at the 1928 Congress included Javanese, Minangs, Malays, Bataks, Banjarese, Bugis, Ambonese, Balinese and Minahassans. However, there were two main reasons for the selection of Bahasa Indonesia.

The first was that although Javanese was the largest ethnicity – 47 per cent according to 1930 census – it was not an overwhelming majority. It would therefore not have been a unifying force for the fledging national movement. If anything, it would have underlined the unhappiness of many non-Javanese about the centralising forces of the Dutch colonial administration in Jakarta.

The second reason was that Javanese was deemed too complex and feudal for a modern state.

What’s driving Indonesian paranoia over Chinese workers?

This view was shared by many prominent Javanese thinkers and leaders. Even Indonesia’s founding father, Sukarno, wrote: “The different variations of Javanese would make it difficult for people to interact freely. [It is] especially hard for those who are not from Central Java or East Java. Should we use ngoko, krama or krama inggil for everyone to speak, regardless of their social status?”

Simply put, there are three “levels” of Javanese based on their formality: ngoko is the lowest level and the most common form; madya or krama madya is in the middle; and krama is the highest.

Furthermore, each level has its own subcategories based on the status of the person being addressed. The krama itself is divided into two forms: krama inggil (high krama) and krama andhap (humble krama). Krama inggil is used at formal events or by people of higher status. Krama andhap on the other hand is used to show respect to others of a higher status by demeaning oneself.

It means communicating in Javanese requires the speaker to be constantly aware of his or her status as well as the status of the people being addressed. Indonesia’s nationalists were committed to egalitarianism and therefore wary of these complexities.

Bahasa Indonesia or Malay, by comparison, emerged as the lingua franca of the entire archipelago. It belonged to all Indonesians and was deemed easier to learn and use.

Activist Ki Hadjar Dewantara, who later became Indonesia’s first minister of education, in 1916 advocated for Malay to be taught to children rather than Bahasa Jawa. Hadjar was born into Javanese priyayi nobility with the name of “Raden Mas Soewardi Soerjaningrat” but dropped his title in a rejection of feudalism.

Bahasa Indonesia has in many ways been an incredible success. In 2010, about 92 per cent of the population claimed proficiency in Bahasa Indonesia, increased from 40 per cent in 1970.

How ethnic Chinese shaped the home of Indonesia’s new capital

Nonetheless, the dominance of Javanese in politics and public life ensures a grasp of the language and its cultural nuances is critical for anyone hoping to understand Indonesia.

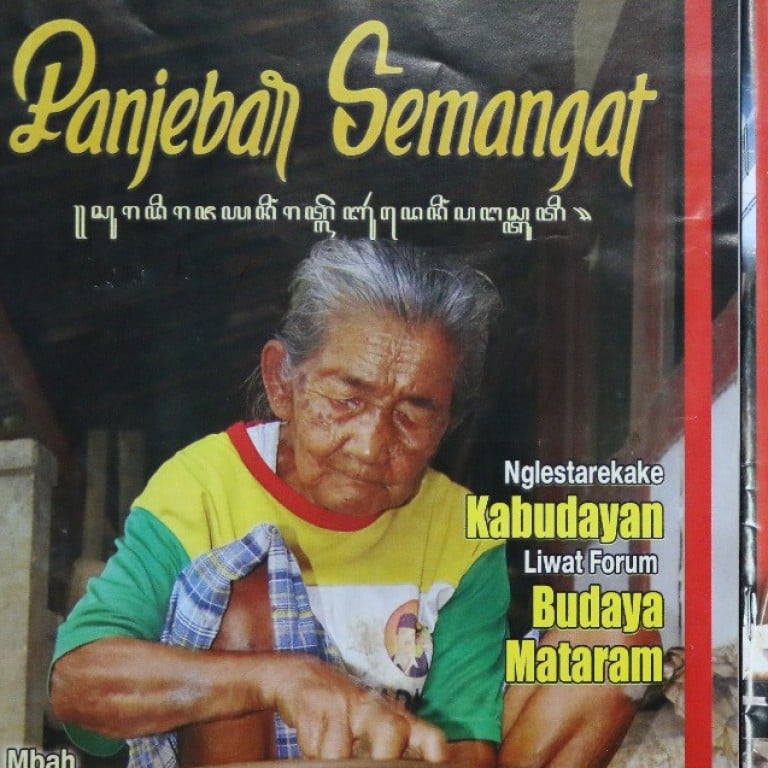

Javanese is also regarded by many as having an incomparably rich literary tradition stretching back many centuries to the writings of Mpu Prapanca, Mpu Tantular, the royal poet Ronggowarsito and the more racy Serat Centhini.

So for all Bahasa Indonesia’s apparent dominance, Javanese remains a powerful and influential undercurrent, infusing public discourse and popular culture. One would be well-advised to bear in mind the Javanese proverb: “Ojo kagetan, ojo dumeh” or “Don’t be too easily surprised and don’t be arrogant.”