In Malaysia, hopes for racial unity as Independence Day approaches. The reality? Growing division

- The country’s multicultural identity becomes a cause for celebration every August as Malaysia gears up for its national day party

- But democratisation is now pushing politicians to exploit ethnic differences for electoral gain, and many fear a slide towards bigotry and radicalisation

“Malaysians are becoming more divided and politics is becoming about expediency rather than uniting the people. People are putting their self-interests ahead of unity,” said political analyst Awang Azman Awang Pawi, from the University of Malaya’s Academy of Malay Studies.

Ethnopolitics had a market, said senator Liew Chin Tong, because of its emotive value and undue emphasis on different backgrounds rather than a shared destiny. “We need to be able to make middle-ground causes emotive too,” said Liew, who is from Pakatan Harapan’s Democratic Action Party. “What we need is empathy. Lifting Malaysians out of poverty, making sure that people have jobs, making sure that people have food on the table … these can be equally emotive.”

Malaysia’s democratisation has proved a double-edged sword as new leaders struggle to execute economic, institutional and legal reforms while retaining the support of Malay-Muslims – the country’s largest vote bank at over 65 per cent of the population.

Malays receive affirmative-action privileges meant to correct income inequalities such as housing discounts and preferential access to education and business – although detractors say the policies have bred resentment and stifled competitiveness. Pakatan Harapan won the 2018 polls with only 30 per cent of the Malay vote, although 95 per cent of the country’s voters of Chinese descent were reported to have backed the coalition.

Where’s Malaysia headed with its race-based preferential policies?

“There is an uncertainty and anxiety among many Malays that their long-standing privileges are currently under threat and not protected by the Pakatan Harapan government. While Barisan Nasional’s formula of having a Malay party at the helm driving the agenda of Malay-Islam supremacy managed to keep these tensions from boiling over, Pakatan Harapan’s component parties are equal in status,” political scientist Azmil Mohd Tayeb said.

This arrangement, he added, resulted in racial “anxiety” that was easily exploited even as “the new political space also allows some non-Malays, non-Muslims and liberal Malays to push for reforms”.

Examples include the resistance against the proposed inclusion of Arabic-Malay calligraphy in the school syllabus which saw the government relenting and making the topic optional, and the widespread criticism of one state’s attempts to amend its law to allow for one parent to unilaterally convert a child to Islam– a thorny topic in Malaysia, where non-Muslims must convert to marry Muslims.

However, this pushback was not without consequence: following the khat matter, police launched investigations into controversial education NGO Dong Zong (the United Chinese School Committees Association) for inciting racial sentiment, and premier Mahathir branded the group “racist”.

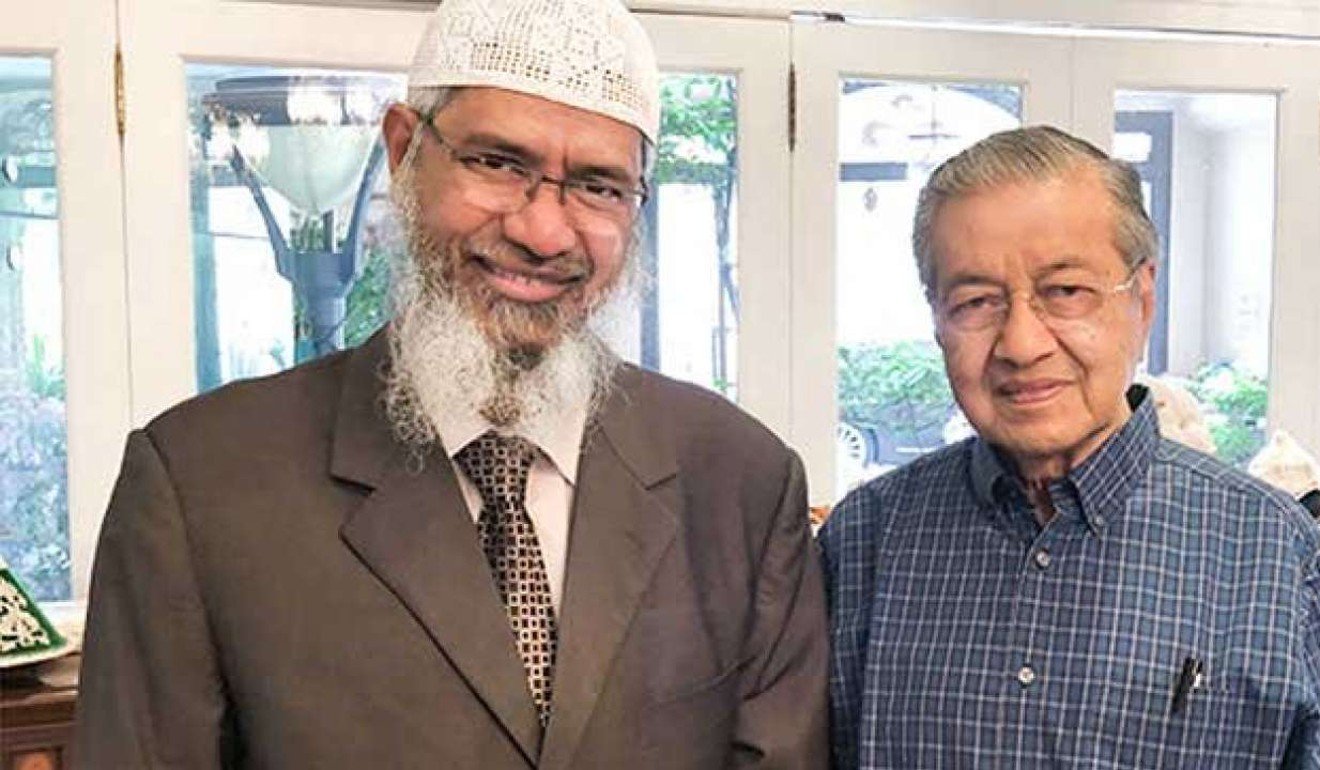

But Pakatan Harapan’s efforts to woo the Malay vote are best seen in the government’s refusal to deport controversial Islamic televangelist Naik, who holds permanent residency in Malaysia.

Facing criminal charges of money laundering and instigating terrorism in his homeland India and banned from several countries for propagating anti-Semitic hate speech, Naik’s presence is seen as support for hardline Islam in a country which has long projected a moderate Islamic image and is home to substantial Christian, Hindu and Buddhist minority communities.

Racial politics: where it all went wrong for the Malaysian Chinese Association

Mahathir, 93, has refused to deport Naik back to India as “he runs the risk of being killed”, despite admitting he was “unwelcome”.

Rais Hussin, a top member of Mahathir’s Malay party, took to Twitter to say deporting Naik would be “a sure death sentence” in Modi’s India, adding that Naik claimed to have been quoted out of context.

Naik has also brushed off demands from Malaysian citizens for his deportation by saying the country’s ethnic Chinese were also “guests” and should “go back”.

“People call me a guest. So I said: before me, the Chinese were the guests. They weren’t born here. If you want the new guest to go first, ask the old guests to go back,” he said at the same talk.

Mirroring racial taunts often used in Malaysia in which ethnic Chinese and Indians are asked to “balik Cina” or “balik India” (return to China or India), Naik’s remarks incensed top leaders, including youth and sports minister Syed Saddiq, who demanded the preacher be deported.

“An attack against our Chinese and Indian brothers and sisters is an attack against all Malaysians. It is ridiculous to even think that my fellow Malaysians are my guests. They are my family, for God’s sake. Enough is enough.”

Saddiq is one of just four cabinet ministers who have demanded Naik be made to leave the country, despite Mahathir’s insistence that nothing can be done, while Home Minister Muhyiddin Yassin promised that any party spreading racist statements would be investigated, regardless of nationality.

Meanwhile, the coalition’s ties have been stressed due to this struggle for primacy, insiders say. An aide to a top state leader complained of “monologues” instead of “dialogues”, while another long-time party worker said there was resentment and interparty racism festering within the grass roots because of these and other issues.

Malaysia’s first-past-the-post electoral system “has not induced backbenchers to be moderate”, says political scientist Wong Chin Huat of Sunway University, despite the top leadership pushing for more moderate stands.

The binary options of the system – a conservative Malay-Muslim opposition or a fragmented Pakatan Harapan – encouraged the government to allow conservative voices to shape its agenda, analyst Azmil said.

Anxieties about Mahathir’s new Malaysia go deeper than race

“Mahathir sees the utility of keeping Zakir Naik around due to his popularity among the Malays. Deporting him will incur the wrath of the Malays, whose votes Mahathir’s party desperately needs now,” he said, adding that while Pakatan Harapan was divided, Mahathir relied heavily on the “unilateral” methods of leadership he practised during his first stint as premier from 1981 to 2003, when he was with Barisan Nasional and often referred to as a dictator.

This was echoed by Awang Azman, who said Mahathir “had his own motives” for allowing Naik to remain, but “he clearly cannot control his cabinet, the coalition and the people” with his old methods of leadership.

Meanwhile, Malaysian police have opened investigations into the preacher for “intentional insult with intent to provoke a breach of the peace” after 115 police reports were filed about his remarks, and the state of Sarawak banned Naik from entry.

Citizens have started several petitions to deport or extradite him, although his supporters have pushed back, describing Naik as a unifying force for Malays and even going as far as to issue online death threats against detractors.

Naik himself has filed a police report alleging that five people, including Human Resources Minister M. Kulasegaran, had defamed him with their statements and articles.

In a video that went viral, Malaysian comedian Jason Leong called on politicians to uniformly reject Naik, asking if it was “the hill [they] want to die on”.

“Our government is filled with men and women who know better. Yet they allow the country to be hijacked by the extremist and vocal minority at the expense of our futures,” Leong told the Post.

In his video, the celebrity lambasted the preacher for his “rude” demands that Malaysia’s ethnic Chinese return to China.

“I am Malaysian, we are Malaysian. This is our country, this is our home. You don’t get to tell us to ‘balik Cina’ – but you should ‘balik India’,” he said.